Part Sixteen: Round Two in the East (1)

(For clarity, German and Austro-Hungarian formations are rendered in italics.)

The so-called Race to the Sea in the west had not yet run its course when Lieutenant-General Erich von Falkenhayn, who had replaced Moltke as Chief of the OHL, turned his attention to the situation in the east. Though Germany had scored two clear victories—Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes—over Russia in the opening round, they were offset by the disasters that had overwhelmed the Austro-Hungarian armies in Galicia and Serbia. The Austrian Chief of Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf, was crying out for help, and Falkenhayn reluctantly concluded that the “Austro-Hungarian emergency” required Germany to reinforce the Eastern Front.

From Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff—the Duo, as the victors of Tannenberg were being called—came a proposal for a large-scale offensive against the Russians in the Polish salient. They argued that such an offensive, with the aim of encircling and destroying a major portion of the Russian Army, could be decisive for the whole war. Conrad naturally supported this idea and demanded the absurd total of thirty German divisions to reinforce his own armies for their part in the operation. All this, of course, would have stood German strategy on its head—with the east replacing the west as the principal theater of war.

Falkenhayn had other ideas. Believing as he did that the war would last a long time and disbelieving in the possibility of decisive victory over Russia, he desired merely to stabilize the situation on the Eastern Front. He therefore rejected the Duo’s proposal and Conrad’s exorbitant demands. Instead, he took two corps from Eighth Army, and two corps and a cavalry division from the armies in the west, using them to set up a new Ninth Army. Hindenburg was appointed to command of the latter, while Ludendorff was to stay as chief of staff of the former. In this Falkenhayn no doubt intended to break up a rival power center in the east, but Hindenburg’s protest to the Kaiser scotched the new command arrangement, and the Duo remained intact.

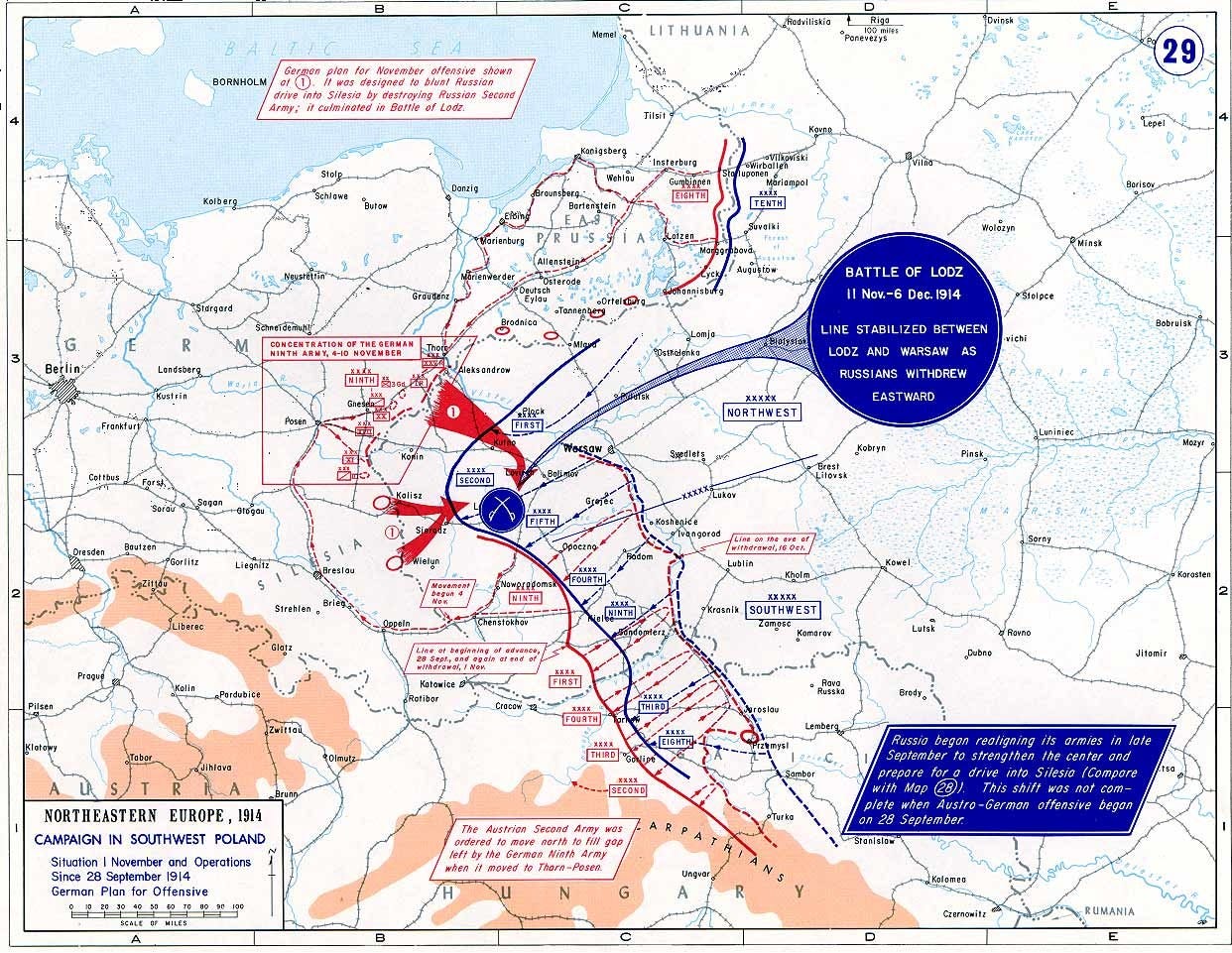

Ninth Army’s headquarters was established at Breslau in southeastern Silesia. It was given the mission of conducting a limited offensive in cooperation with the Austrians, the objective of which was to push back the Russians from the Silesian frontier. Falkenhayn calculated that such an offensive would compel the enemy to transfer forces from the southern sector of the front, thus relieving pressure on the Austrian armies farther south. If in the process a sharp defeat could be inflicted on the Russians, well and good—but as Falkenhayn pointed out to Conrad and the Duo, the rainy season was fast approaching. Its onset would turn the roads to mud, severely limiting the mobility of the armies.

On 18 September, Ludendorff arrived at Conrad’s headquarters, Armeeoberkommando or AOK, to discuss the details of the offensive. It was agreed, reluctantly on Conrad’s part, to strike at the joint between the two Russian army groups, Northwest Front and Southwest Front. Ninth Army would make the main effort, attacking northwest toward Warsaw, its right flank being covered by Austro-Hungarian First Army (General of Cavalry Viktor Dankl von Krasnik). Ninth Army had nine infantry divisions, one cavalry division, three Landwehr divisions and four Landwehr mixed brigades. First Army had nine infantry divisions, two cavalry divisions and some Landstrum (militia) brigades.

As for the Russians, they had already been reinforcing the Polish salient with troops taken from East Prussia and the southern sector of the front. The Russian commander-in-chief, Grand Duke Nicholas, had been under pressure from the French to move against Germany, and after some squabbling he agreed to do so. As a first step, Northwest Front’s Second and Fifth Armies would mount an invasion of Silesia. The Silesian operation would be followed by a drive on Berlin, less than two hundred miles further west. Thus the Austro-German offensive was not really necessary as a means of taking pressure off the Austrian armies on the southern sector of the front. The Duo had the bit between their teeth, however, and their offensive was launched on 28 September.

Ninth Army made good progress at first. But as Falkenhayn had foreseen, the autumn rains soon turned the roads into a morass, greatly impeding the movement of supplies and the heavy artillery. Consequently, Ninth Army did not reach the line of the Vistula River until 9 October, with First Army on its right lagging farther and farther behind.

This unsatisfactory state of affairs was not improved by growing friction between the German and Austrian commands. Ludendorff’s characteristic tactlessness during the planning phase had greatly offended the Austrians, and matters were not improved by German complaints about their ally’s alleged lethargy. “Everything’s fine here except for the Austrians,” Ninth Army’s chief of operations, Colonel Max von Hoffman, wrote in his diary on 8 October. “If only the wretches would move!”

More problems followed. German attempts to cross the Vistula River were repulsed, casualties were mounting, and by 18 October Ludendorff was aware that the Russian buildup posed a serious threat to his left flank. His pleas for reinforcements were rejected by OHL. On the left flank of Ninth Army and less than twenty miles from Warsaw was XVII Corps (General of Cavalry August von Mackensen), five divisions strong. Intercepted radio messages and captured documents revealed that the Russian Fifth Army was concentrating some fourteen divisions against XVII Corps, leaving Ludendorff no choice but to order its withdrawal some forty miles to the west.

As XVII Corps drew back, First Army finally arrived at the line of the Vistula, establishing contact with Ninth Army’s right flank. Ludendorff now conceived the idea of renewing the attack in the great bend of the Vistula—a risky undertaking in view of the Russians’ growing margin of superiority. But he was saved from his folly by the greater folly of Conrad. Having grown weary of his de facto subordination to the Germans, he decided to show them what he and his army could do. He ordered Dankl to let the advancing Russian Fourth Army cross the Vistula near Ivanvogrod, then hit its left flank.

This audacious plan might well have succeeded if German troops had executed it. But First Army was in bad shape: Heavy casualties, supply problems, and exhaustion had sapped the spirit of the men. Contrary to the complaints of the Germans, the Austrians had thus far fought well if not brilliantly, but now they were at the end of their tether. Fourth Army duly crossed the river; the Austrians duly launched their flank attack. It duly failed and the Russians promptly counterattacked. In the ensuing battle, First Army suffered 40,000 casualties and to avoid total disaster, Dankl ordered a general retreat.

Farther south, however, the Austrian armies were able to regain some ground. Having lost so many divisions to Northwest Front, Southwest Front elected to trade space for time, withdrawing from river line to river line. The Austrians relieved the besieged fortress of Przemysl on 9 October, but thereafter their advance petered out and by mid-November most of the recaptured territory was back in Russian hands, with Przemysl once more besieged.

By late October, the Duo had to admit that their own offensive had shot its bolt. The First Battle of the Vistula, as it later was dubbed, cost the Germans some 100,000 thousand casualties, with 36,000 killed. Hindenburg ordered a general withdrawal that took Ninth Army almost back to its start line. The retreat was orderly and methodical; the Russians, suffering from supply problems and hampered by German destruction of bridges and rail lines, followed up haltingly. But the whole performance had to be chalked up as a Russian victory: The pressure on the Austrians in the south had been relieved but temporarily, and most of the Polish salient remained under Russian control. Nothing daunted, however, Ludendorff immediately began planning new offensives—one against the Russians and one against the Chief of the OHL.