Part Ten: Opening Round in the East (5)

(For clarity, Austro-Hungarian units are rendered in italics.)

Though Germany scored a clear victory in East Prussia, it was offset, if not negated, by the disasters that engulfed the armies of the Habsburg Monarchy.

The prewar agreement between the German and Austro-Hungarian general staffs had provided for an Austrian offensive in Galicia—this to relieve pressure on the scanty German forces defending East Prussia. Such an offensive would necessitate the deployment of the bulk of the Austro-Hungarian Army in Galicia, leaving minimal forces to screen Serbia. But the Austrian Chief of Staff, General Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, was ill content with this arrangement. Though Russia posed the most serious military threat, he and most leading figures of the Habsburg Monarchy viewed Serbia’s pan-Slavic aspirations as an even greater menace. The Serbs’ desire to unite the south Slavs in a single kingdom under their leadership implied the demise of the Monarchy. Thus Conrad was determined to “strike down Serbia with rapid blows” while standing on the defensive in Galicia—this despite his promise to the Germans. But the Austrian Chief of Staff's duplicity only succeeded in making a muddle of his army's mobilization.

For purposes of mobilization, the Austro-Hungarian Army was divided into three contingents. A-Staffel (thirty infantry divisions plus cavalry) was earmarked for Galicia. Minimalgruppe Balkan (eight divisions plus cavalry) was earmarked for the Serbian front. B-Staffel (ten divisions plus cavalry) was the strategic reserve. In the event of a limited war between Austria and Serbia, it would reinforce Minimalgruppe Balkan. If Russia entered the war, it would join A-Staffel in Galicia.

But Conrad's desire to strike at Serbia upended this arrangement. When mobilization was ordered, B-Staffel (Second Army), was initially directed against Serbia. Then German protests over his failure to launch the agreed-upon Galician offensive compelled Conrad to attack there after all. The Chief of Staff therefore redirected Second Army to Galicia. But the chief of the mobilization section of the General Staff protested that such a last-minute change would cause chaos on the rail system. Second Army would have to go to the Serbian front anyway, there to await the clearance of the rail lines. Not until 16 August would it be possible to get the army on the move to Galicia. In the meantime, it was partly drawn into the Serbian invasion and, thanks to the ill success of the Austrian offensive, when the time came to move north one-third of it (IV Corps with two divisions) had to be left behind. Thus Second Army arrived in Galicia both late and understrength.

The Austrian commander on the Serbian front, Feldzeugmeister (General of Artillery) Oskar Potiorek, was eager to present the Emperor Franz Joseph with a victory for his birthday (18 August). He therefore launched his offensive on 12 August with Fifth Army (General of Cavalry Liborius Ritter von Frank) and elements of Second Army (General of Cavalry Eduard Freiherr von Böhm-Ermolli). Sixth Army (under Potiorek’s personal command) had not yet completed its concentration. Fifth Army had four infantry divisions, two infantry brigades, a mountain brigade, a Landstrum (militia) brigade and some cavalry. Second Army committed its IV Corps (General of Cavalry Tersztyanszky von Nadas). The grand total was about 285,000 men.

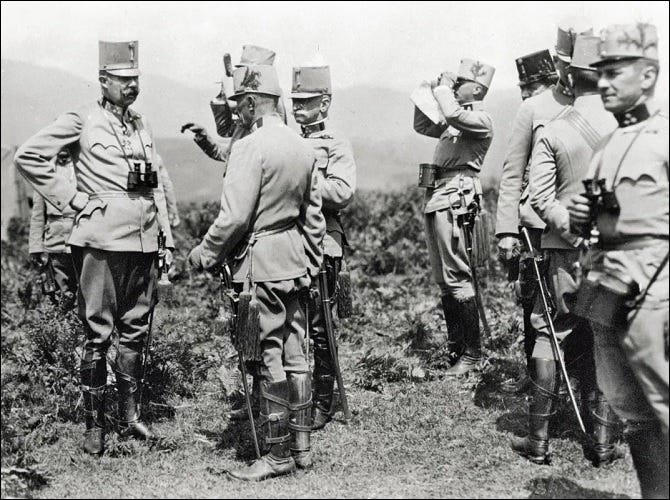

Potiorek exuded confidence, imagining that his troops would easily rout the primitive and ill-equipped Serbs, whom he scorned as an army of "pig farmers." But his confidence was badly misplaced. It was true that the Serbian Army was short of modern weapons and even boots for its soldiers, but it was a battle-hardened force under a skilled and redoubtable commander, Marshal Radomir Putnik.

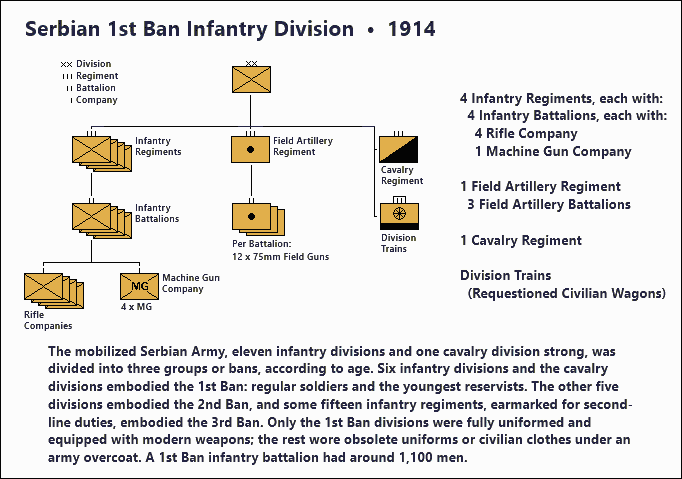

His forces, totaling eleven infantry divisions, a cavalry division and a number of independent brigades and regiments, were divided into three field armies, (actually the size of corps): about 250,000 men in all. However, only active soldiers and the youngest class of reservists, forming the six infantry divisions of the so-called 1st Ban (mobilization group), were armed with modern weapons and wore the new khaki field uniform. The five 2nd Ban divisions received obsolete weapons and old blue uniforms, while those of the 3rd Ban wore civilian clothes and were armed with hunting rifles, shotguns, even old muzzle-loading muskets.

The Austrian offensive made good progress at first, the concentric attacks of Fifth Army and IV Corps forcing the Serbs from one position after another. Belgrade, the Serbian capital, was close the Austrian border and poorly fortified; it soon fell. But as Putnik withdrew he concentrated his army in preparation for a counterattack. This was delivered on 15 August in the vicinity of Cir Mountain, primarily against Fifth Army. The Austrian positions on the slope of the mountain were lightly held and they were forced back. Three days of heavy fighting followed with high casualties on both sides, and ultimately Potiorek was compelled to order a general retreat.

Fifth Army was shattered: Some 38,000 men had been killed or wounded, with another 4,000 taken prisoner. Many of the army’s units had lost all cohesion. The Serbs also suffered heavily, with some 5,000 killed and 15,000 wounded. But by 20 August the Austrians had been chased entirely out of Serbia—a painful setback for a country that still counted itself a great power.

At the urging of the Russians, the Serbs followed up on their victory with an invasion of Bosnia. The idea was to prevent the transfer of Second Army to Galicia, but by the time Putnik commenced his attack Second Army was gone. The Serbian First Army did gain a foothold in Bosnia, but this position had to be abandoned when the Austrians mounted their second invasion.

This was launched in September, Potiorek attacking with the reorganized and reinforced Fifth Army and Sixth Army, now fully mobilized. The former, attacking across the Drina River as it had in August, was repulsed. But farther south the stronger Sixth Army (five infantry divisions, one Landstrum brigade and some cavalry) had better luck. It managed to establish itself on Serbian territory and its success also levered the Serbian forces facing Fifth Army out of their positions. The fighting again was fierce, with each side suffering heavy casualties before a stalemate was reached.

There followed a month and a half of static trench warfare. In November, the Austrians opened a new offensive but after an encouraging start it broke down in the face of a Serbian counterattack that routed Sixth Army. When the fighting subsided in early December, no Austrian soldiers, prisoners of war excepted, remained on Serbian soil. The debacle being complete, the hapless Potiorek—who as military governor of Bosnia had presided over the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand—was relieved of his command. Ritter von Frank, the commander of Sixth Army, was also sacked.

While Potiorek’s initial operations in Serbia were proceeding on their lamentable course, the main body of the Austro-Hungarian Army, A-Staffel with thirty infantry divisions and eight cavalry divisions, was being deployed in Galicia. From left to right, these forces were allotted to First Army, Fourth Army and Third Army. By late August they had completed their march to the frontier (necessitated by Conrad’s earlier decision to stand on the defensive inside Galicia) and were ready to attack.

The Austrian plan, sound enough in principle, was to advance north-east into Russian Poland with First and Fourth Armies on the left, capturing the towns of Lubin and Chom, unhinging the Russians' right flank and compelling them to withdraw. But thanks to Second Army’s non-appearance, there were insufficient troops to carry out the operation. As First and Fourth Armies advanced, the right flank of the latter would be increasingly exposed. It was to have been the task of Second and Third Armies to screen this exposed flank. But for the latter alone, this proved to be a mission impossible.

Conrad was well aware of the unpalatable facts: that Russian mobilization would inevitably bring more and more divisions into the line against the Austrian armies, and that thanks to Second Army’s late arrival the pressure on the Austrian right flank was bound to reach crisis proportions. Nevertheless, he persisted and the general Austro-Hungarian offensive in Galicia commenced on 22 August 1914.

The numbers killed in these battles is staggering. Always read about the one in the western front.