Part Ten: Opening Round in the East (5)

(For clarity, Austro-Hungarian units are rendered in italics.)

The Russian forces facing the Austrians along the Galician frontier consisted of four armies under an army group headquarters, Southwestern Front, commanded by General of Artillery Nikolay Ivanov. In the northern sector, Fourth Army (General of Infantry Aleksei Evert) and Fifth Army (General of Cavalry Pavel Pleve) stood opposite the Austrian First and Fourth Armies. Farther south, Third Army (General of Infantry Nikolai Ruzsky) and Eighth Army (General of Cavalry Aleksei Brusilov) faced Third Army. There was no Austrian army group headquarters; the high command (Armeeoberkommando or AOK) controlled operations directly. The nominal Austrian Commander-in-Chief was General of Cavalry Archduke Friedrich, but actual command was exercised by the Chief of Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf.

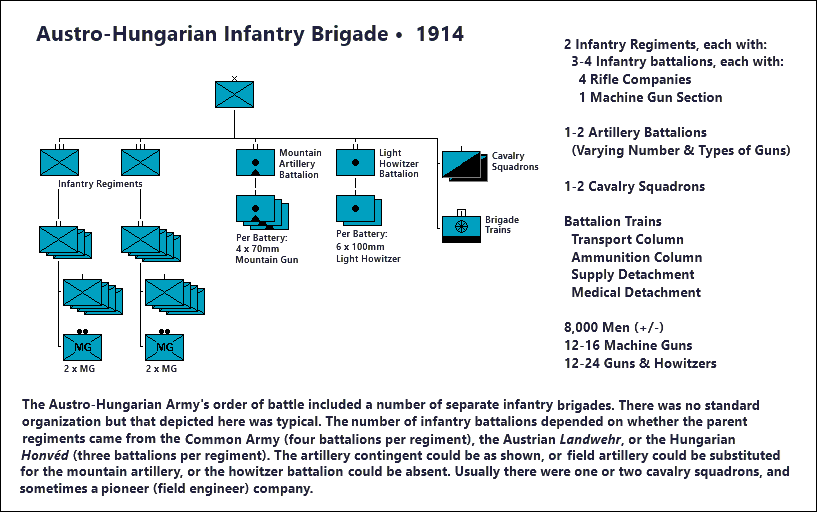

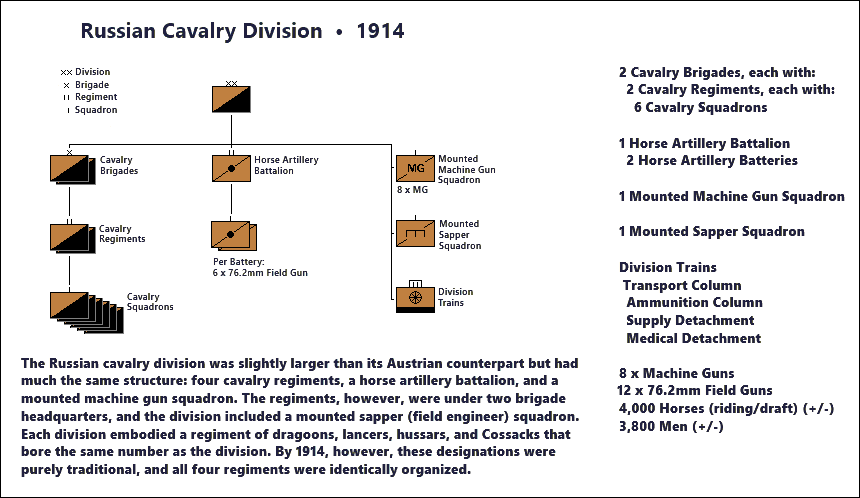

After some preliminary engagements—including a large-scale Austrian cavalry raid that accomplished nothing in particular—the main Austrian offensive commenced on 22 August 1914. Because Stavka (the Russian high command) had expected the enemy’s main effort to be made farther south, the Austrians enjoyed a measure of numerical superiority in the northern sector. First Army (General of Cavalry Viktor Dankl) had ten infantry divisions, one infantry brigade and two cavalry divisions against Fourth Army’s six infantry divisions, one infantry brigade and three cavalry divisions. Fourth Army (General of Infantry Moritz Ritter von Auffenberg) and Fifth Army were about equal in strength, though the former with its high proportion of regular officers and NCOs was of superior quality.

Farther south, Third Army (General of Cavalry Rudolf Ritter von Brudermann) and the Kövess Group were detailed to screen the right flank of Fourth Army. The latter was an ad hoc formation under the commander of Third Army’s XII Corps (General of Infantry Hermann Freiherr Kövess von Kövesshaza), consisting of that corps plus a few units of Second Army that had reached Galicia from the Serbian front. The Austrians were heavily outnumbered in this sector: Between them, the Russian Third and Eighth Armies had sixteen infantry division and eight cavalry divisions against Brundermann’s eleven infantry divisions and five cavalry divisions. Nor would the belated arrival of the bulk of Second Army improve matters for the Austrians. With its mobilization complete, the Russian Army’s margin of superiority would continue to widen in the weeks ahead.

Conrad knew that unless his forces gained a quick victory in the northern sector, his offensive was unlikely to succeed. And there was, as he said later, “a happy beginning.” First Army scored a clear victory over Fourth Army in the Battle of Krasnik (23-25 August), inflicting some 25,000 casualties and driving the Russians back in disorder. Fourth Army enjoyed similar success against Fifth Army in the Battle of Komarów (26 August-2 September). This was a hard-fought action, as the Austrians enjoyed no superiority of numbers. But Fifth Army had been shaken by the defeat of Fourth Army on its right flank and its resistance collapsed. Casualties, including 20,000 men made prisoner, were extremely heavy. Had it not been for prompt action by Plehve, the army commander, who ordered an immediate retreat, Fifth Army might well have been encircled and destroyed.

But these Austrian successes in the north were more than offset by the increasingly ominous situation farther south. Despite his success at Komarów Auffenberg, the Fourth Army commander, fretted about the security of his right flank, which was supposed to be covered by Brundermann’s Third Army and the Kövess Group. “We’re not in a good position,” he remarked to his chief of staff, and he pointed out to Conrad that Brudermann lacked sufficient forces to carry out his mission.

For his part, Brudermann was spoiling for a fight. He implored Conrad for permission to go over to the offensive against the Russians in his sector. Hitherto, Third Army and the Kövess Group had remained echeloned to the rear of Fourth Army, in line with their task of flank protection—a task that was becoming more and more difficult thanks to the non-appearance of Second Army and the Russians’ growing strength. But as with Moltke, who yielded to the pressure of his commanders on the left flank to expand the offensive against the French, that “happy beginning” in the north put the scent of victory in Conrad’s nostrils. Irresistibly tempted by the possibility of a double envelopment of the Russian forces in Galicia, he gave Third Army permission to attack.

Seldom has a military action been worse timed. Beginning on 26 August, Third Army advanced with three corps—some nine divisions—against Third and Eighth Armies, which between them had some twenty divisions in eight corps. Third Army collided with this greatly superior force on the line of the Zlota Lipa River, received a thorough drubbing and was driven from the field. Near Brzezany, the Kövess Group was also thrown back, narrowly escaping encirclement in the process.

Conrad ordered a new line to be formed on the Gnila Lipa River, which was possible only because the Russians took two days to sort themselves out before resuming their advance. Desperate to maintain the initiative, he ordered III Corps of Third Army to counterattack on 29 August. It was a fiasco. Overall, the Russians had 292 infantry battalions and 1,304 guns against the Austrians’ 115 infantry battalions and 376 guns. The Austrians were stopped dead in their tracks, then driven back amid scenes of panic and rout. In a single day of fighting III Corps lost 20,000 men and almost a hundred guns, effectively knocking it out as a fighting force.

Having been soundly defeated, Third Army and the Kövess Group fled to the west. The fortress of Lemberg fell to the Russians on 3 September. Only the arrival from Serbia of Second Army’s VII Corps prevented a complete collapse. Brudermann, a former Inspector-General of Cavalry once touted as the “boy wonder” of the Habsburg Army, was ignominiously dismissed from his command.

And worse followed. Third Army’s stinging defeat fatally undermined the position of the hitherto successful First and Fourth Armies. Persuading himself that the Russian armies in the northern sector no longer constituted a major threat, Conrad ordered Auffenberg’s Fourth Army to sidestep to its right, the idea being to bolster up the tottering Third Army. But this move had the unfortunate result of creating a gap between First and Fourth Armies, with nothing available to fill it but some cavalry. Nor were the Russians in the northern sector down for the count. Reinforcements had been flowing to Southwest Front and Plehve’s Fifth Army was back up to strength. He was ordered to attack and did so on 3 September, striking the weak joint between the Austrian armies. By 11 September the left flank of Fourth Army had been smashed, compelling both it and First Army to commence a retreat that only ended on the line of the Carpathian Alps.

By 26 September, the debacle was complete. Most of Austrian Galicia had fallen under Russian occupation; the fortress city of Przemysl with its garrison of 100,000 Austrian troops was surrounded and besieged. In all, the armies of Austria-Hungary had suffered some 500,000 casualties, including many irreplaceable professional officers and long-service NCOs.

Conrad von Hötzendorf’s Galician adventure thus inflicted a wound on the Austro-Hungarian Army from which it would never fully recover. And the parlous condition of its ally soon compelled the new German Chief of Staff, General of Infantry Erich von Falkenhayn, to dispatch reinforcements from west to east. The “Austro-Hungarian emergency” would exercise a dominant influence on the Central Powers’ conduct of the war in 1915.

It is amazing how often stellar peacetime generals are found wanting in war.

The lesson is that the skills required for success in peace often don't translate to a wartime situation.

Or conversely, the skills required of a successful wartime soldier are often not identified in a peacetime army.

I wonder how Gen. Milley (supporter of woke education, masterful leader of the Afghan debacle, and Chinese communicator extraordinaire) would have done in war.

I suspect that he (and we) are lucky that he retired.