News of the disastrous Battle of Coronel (1 November 1914) struck the Admiralty in London like a bolt of lightning. Coming on the heels of the Goeben debacle, the loss of two armored cruisers with all hands was a humiliation for the Royal Navy that profoundly shocked the British public. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, and the new First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John “Jackie” Fisher, realized that decisive action was necessary to staunch the bleeding, and it was decided to send powerful reinforcements to the South Atlantic. The battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible were detached from the Grand Fleet and sent to Devonport to prepare for deployment to the South Atlantic. Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee, Chief of the Naval Staff, was appointed to command the squadron, comprising the battlecruisers and all ships already in the area, as Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic and Pacific, with his flag in Invincible.

Sturdee owed his appointment to Churchill. When Fisher replaced Prince Louis of Battenberg as First Sea Lord, he intended to sack Sturdee, an old rival from prewar days whom he blamed for the Coronel disaster. But the Chief of Naval Staff refused to go quietly, so to prevent a scandalous row the First Lord suggested that he be promoted out. Fisher reluctantly agreed, adding the acid comment that Sturdee deserved to be stuck with the job of cleaning up the mess he’d made.

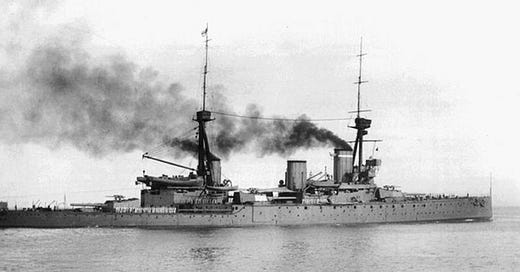

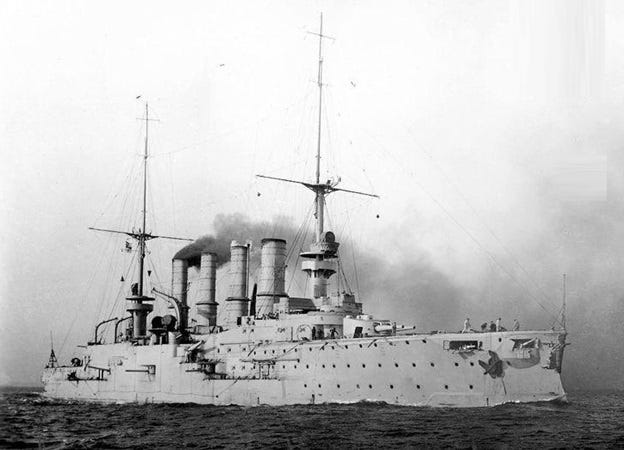

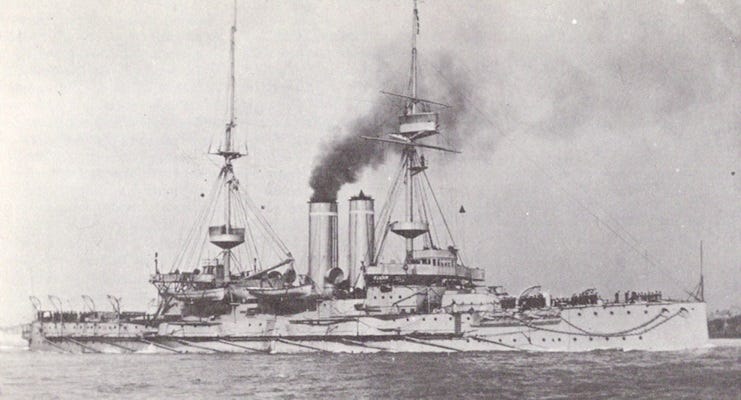

Churchill and Fisher certainly gave the new Commander-in Chief, South Atlantic and Pacific, the tools he needed to get that job done. The two British battlecruisers, with their maximum speed of 25 knots and main armament of 8 x 12in guns in four twin turrets, were more than a match for the armored cruisers of Vice-Admiral Graf Maximillian von Spee’s Ostasiengeschwader (East Asia Squadron). Scharnhorst and Gneisenau’s maximum speed was 22.5 knots, and they carried a main armament of 8 x 8.2in guns in two twin turrets and four casement positions. It was certain, therefore, that if Sturdee’s squadron could bring the Ostasiengeschwader to battle, it would be destroyed.

As the British battlecruisers prepared to sail, Spee lingered off the coast of Chile, calling at Valparaíso and the port of Bahia San Quintin. The question for the Germans was what to do next. Most of Spee’s officers favored an attempt to return to Germany, and that was the course of action decided upon. The Ostasiengeschwader set sail for Cape Horn, pausing at Picton Island, off Tierra del Fuego, to distribute coal from a captured British collier, then passing into the South Atlantic on 4 December. Spee had two armored cruisers, three light cruisers and three transports under command. His intention was to conduct a bombardment of the Royal Navy station at Port Stanely in the Falkland Islands before making for Germany.

Meanwhile, Invincible and Inflexible completed their preparations and sailed for the Falklands on 11 November. The need to conserve fuel meant that their passage was leisurely, steaming at 10 knots. In anticipation of Sturdee’s arrival, the Admiralty sent instructions to Captain Heathcoat Grant, commanding the old battleship Canopus, to organize the defenses of Port Stanley in case the Germans attacked. He was told to beach his ship in a position allowing its four 12in guns to command the approaches to Port Stanley, establish observation posts ashore, throw a mined barrier across the harbor entrance, and send his ship’s 12-pounder (3in) guns and their crews ashore to serve as coast defense artillery. As a matter of fact, Grant, an able and experienced officer, needed no such orders; he had already set these defensive measures in motion.

Sturdee arrived at the Abrolhos Rocks, off the coast of Brazil, on 26 November. There he rendezvoused with Rear-Admiral Archibald Stoddart’s Mid-Atlantic Squadron of three armored cruisers and two light cruisers, including Glasgow, sole survivor of the Coronel disaster. And there he intended to remain for three days while his ships refueled and took on stores, and their crews enjoyed some shore leave. This appalled John Luce, Glasgow’s captain, who insisted that the squadron should depart for the Falklands without delay. Sturdee allowed himself to be persuaded, and he sailed the next day, 27 November, arriving at Port Stanley on 7 December.

The stage thus seemed to be set for the destruction of the Ostasiengeschwader—but when Spee arrived off Port Stanley on the morning of 8 December, he was presented with a fleeting opportunity to score an even bigger victory over the British.

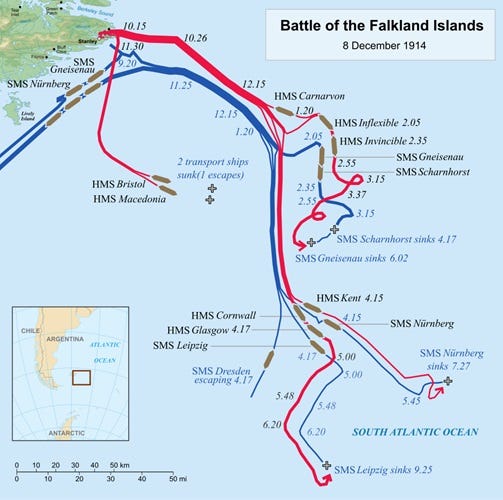

At the time of the Germans’ appearance the British ships were disposed as follows. Sturdee’s two light cruisers, Glasgow and Bristol, were moored in the inner area of Stanley Harbour. The battlecruisers and armored cruisers were moored in Port William, the deeper outer harbor. Some of the British ships were coaling, which sent up a cloud of coal dust over the anchorage. The armed merchant cruiser Macedonia was on patrol off Port Stanley; the armored cruiser Kent lay in the harbor, steam up in readiness to relieve Macedonia.

In short, all the British warships but two were unprepared for action when the Ostasiengeschwader arrived on the scene. It was just possible that a prompt bombardment of the harbor would have caused havoc and, probably, the loss of several ships.

Spee, however, had no inkling that the British squadron was present. The latest information he had from German sources in South America indicated that there were no British warships at Port Stanley. He therefore sent in two of his ships, Gneisenau and Nürnberg, to bombard what he thought was an empty harbor. But as they approached, smoke (actually the cloud of coal dust) was observed over Port Stanley. Captain Maerker of Gneisenau thought at first that the British had set their coal store on fire to prevent its capture. Moments later, however, the masts of numerous ships were spotted, including the distinctive tripods of enemy battlecruisers. And then, to Maerker’s consternation, a salvo of heavy shells struck the water close to his ship.

What had happened was this. One of Captain Grant’s shore-based observation posts had sighted the Germans and flashed the news to him via telephone. Thanks to that enveloping cloud of coal dust, however, it took time to get a message to Sturdee. When he finally received it, the admiral ordered his ships to raise steam and sortie. But at that moment, they were fat targets for the Germans.

The day was saved for the Royal Navy by that old veteran, Canopus. Providentially, her 12in guns were manned and ready, Grant having arranged for a morning practice shoot with inert training rounds. The guns were already loaded when the alarm was sounded, and the first two salvos fired by Canopus contained no high explosive. But the old battleship’s shooting was excellent. Her second salvo straddled Gneisenau; one round ricocheted and struck one of her funnels. Maerker, assuming that it was a dud, turned about, and the Ostasiengeschwader’s one chance to turn the tables on the much superior British was gone.

When Gneisenau’s report reached Spee, the German admiral knew he was doomed, but even so he made a fight of it. When the British battlecruisers finally cleared the harbor at around 10 a.m., he had a fifteen-mile lead on them. It was not until 1 p.m. that they got within extreme range of the German ships. But when they opened fire, their shooting was poor. For his part, realizing that he could not outrun the enemy battlecruisers, Spee decided to engage them with his armored cruisers alone, so as to give his light cruisers and transports a chance to escape. He turned to engage at 1:20 p.m.

At first the British were hampered by their own funnel smoke, which prevented them from ranging accurately on Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. This enabled Spee to close the range and open fire. German gunnery was accurate as always: Their salvos straddled the battlecruisers again and again, and Invincible was hit several times by 8.2in and 5.9in shells. They did no serious damage, however, and as the fight went on, the British ships’ superior weight of fire began to tell.

Sturdee ordered his armored cruisers and light cruisers to chase down the German light cruisers and transports, while his battlecruisers dispatched the German armored cruisers. Scharnhorst was heavily hit as Spee continued to close the range; she was set afire and acquired a list, and sank at 4:17 p.m., taking all hands to the bottom with her. Gneisenau continued to engage the enemy, but though badly battered by 12in hits she only ceased fire when her ammunition was exhausted. She finally sank at 6:02 p.m., leaving 190 survivors in the water to be picked up by Inflexible. Though the German armored cruisers had scored some forty hits, the damage done to Invincible and Inflexible was slight. One British sailor was killed and several were wounded.

Of the fleeing German light cruisers and transports, only one of each escaped. Nürnberg was sunk by armored cruiser Kent after a boiler explosion had cut her speed. Leipzig fought the armored cruiser Cornwall and light cruiser Glasgow until she ran out of ammunition, then rolled over and sank. Other British ships ran down and sank two of the German transports. In all, 217 German sailors survived the battle: 190 from the armored cruisers, nine from Nürnberg, and eighteen from Leipzig. The crews of the two unarmed transports also survived; they were taken off before their ships were sunk.

Only light cruiser Dresden and transport Seydlitz escaped. The cruiser survived for three more months. She was finally run down by a British squadron in the Juan Fernández Islands off the coast of Chile. After a short engagement her captain, judging the situation to be hopeless, ordered Dresden to be abandoned, then destroyed with demolition charges.

Thus Coronel was avenged. Admiral Sturdee was hailed as a hero—much to the annoyance of Jackie Fisher, whose opinion of the man he expressed with characteristic intemperance: “…a pedantic ass, which Sturdee is, has been, and always will be!” But the Battle of the Falklands did much to restore confidence in the Royal Navy after its bad start in the war. And it was decisive in its results. Except for three light cruisers that were chased down and destroyed in the next few months, the Kaiserliche Marine’s threat to Allied shipping had been eliminated. Later the Germans would resort to surface raiding by auxiliary cruisers disguised as merchantmen and unrestricted submarine warfare, but never again in the war would a German battle squadron range over the Atlantic or Pacific oceans.

A very interesting account, Thomas, thank you for this post. I only wish you had posted a couple of months earlier prior to my visit to Port Stanley.

Excellent work!

The whole series of incidents is gripping reading in Churchill's memoirs, The World Crisis.