If its failure to run down Goeben in the Mediterranean was an embarrassment, the first phase of the naval war in the Pacific ended in disaster for the Royal Navy.

When war broke out in August 1914, British and Australian naval forces in the Pacific busied themselves with the capture of Germany’s colonies in the area: Kaiser-Wilhelmsland (northern New Guinea), Yap, Nauru, and Samoa. The German naval presence in the western Pacific, the Ostasiengeschwader (East Asia Squadron), was based at the German concession of Tsingtao in China, and would, it was assumed, be dealt with by Japan, which in accordance with the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902-11 was expected to declare war on Germany.

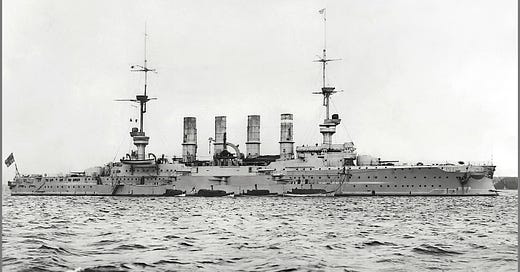

The main units of the German squadron were two armored cruisers, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and three light cruisers. The armored cruisers were the newest ships of that class in service with the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy), built in 1905-08 specifically for foreign service. Their main armament consisted of 8 x 8.2in guns, disposed in two twin turrets on the centerline fore and aft, and in four casement positions port and starboard amidships, to provide a six-gun broadside. Secondary armament was 6 x 5.9in guns in in six casement positions port and starboard amidships. Close-range defense against torpedo boats was provided by 18 x 3.4in guns mounted in the superstructure. Like most large warships of the period, the ships were also fitted with four submerged torpedo tubes. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were designed for a maximum speed of 22.5 knots, which they slightly exceeded in service. The three light cruisers had been constructed between 1905 and 1909; they were armed with 10 x 4.1in guns and torpedo tubes and were designed for a maximum speed of 23.5 knots.

The Ostasiengeschwader also included various older and smaller warships, gunboats, patrol vessels, etc. It was supported by a network of colliers and supply ships, prepositioned across the Pacific by the German Admiralty.

The outbreak of war in early August 1914 led the German commander, Vice-Admiral Graf Maximillian von Spee, to leave Tsingtao with his armored cruisers and light cruisers. It was likely that Japan would soon declare war on Germany, the Japanese Navy was large and powerful, and Spee was anxious to be away before that declaration came (which happened on 23 August). The Ostasiengeschwader slipped out of Tsingtao, disappearing into the vastness of the Pacific. The German ships proceeded independently, with orders to rendezvous at Pagan Island in the Marianas, where they could refuel from a collier. At Pagan Island, the auxiliary cruiser SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich, a former passenger liner, joined the squadron.

While at Pagan Island, Spee decided to detach the light cruiser Emden and Prinz Eitel Friedrich and send them to the Indian Ocean with the mission of commerce raiding. With the rest of his squadron, he determined to make for the west coast of South America. The nitrates, copper and other minerals, the grain, beef and lamb that Britain imported from South American countries were vital to its war effort—a fact that concentrated minds in the British Admiralty when word reached it that the German squadron was heading east.

That word was some time in coming. For weeks, the Ostasiengeschwader’s whereabouts remained a mystery. It was true that the Allied naval forces in the region greatly outnumbered Spee’s handful of ships. But the Pacific was a large ocean and the odds of encountering the German squadron so small it was not until mid-September that radio intercepts gave some indication of its course. These hints were confirmed on 22 September when Scharnhorst and Gneisenau appeared off the port of Papeete at Tahiti, French Polynesia. Spee’s main objective was to capture the large supply of coal at Papeete, but in this he was frustrated.

The French authorities had been warned that a German attack was possible, but the defending forces consisted of shore-based batteries whose guns were outraged by those of the Germans armored cruisers, and a single antiquated gunboat. The shore batteries fired warning shots as Scharnhorst and Gneisenau approached; they replied with a warning shot of their own and hoisted their battle ensigns, signaling a surrender demand. When the French refused, the Germans opened a bombardment. At first they concentrated on the French shore batteries, but it proved difficult to locate them and fire was shifted to the ships in the harbor: the French gunboat and a captured German cargo ship. Both were sunk and fire was then shifted to the town. By the time that Spee ordered a withdrawal, a large part of Papeete had been destroyed. The French themselves had set the coal piles alight, to prevent their capture. Casualties were slight, however: Only two civilians were killed, and no military personnel were killed or wounded. The German ships sustained no damage.

After withdrawing, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau rendezvoused with Nürnberg and the auxiliary cruiser Titania at Nuku Hiva, largest of the Marquesa Islands in French Polynesia, then proceeded to Easter Island for a rendezvous with the rest of the Ostasiengeschwader. Spee, now aware that the Royal Navy was on his track, decided to proceed as planned to the waters off the coast of Chile, then sail around Cape Horn into the Atlantic.

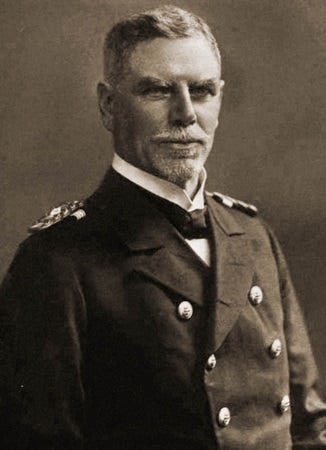

An intercepted radio message on 4 October alerted the British to Spee’s intentions, and the Admiralty in London set in motion a naval deployment intended to trap and destroy him. The principal British force in the area was the main body of the West Indies Squadron, Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher “Kit” Cradock commanding. This officer, celebrated for his pugnaciousness, had two armored cruisers, one light cruiser and one auxiliary cruiser under command. The armored cruisers, HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth, had been laid down at the turn of the century and entered service in 1902-03. Both were in reserve when the war broke out and were recommissioned for service with crews consisting mainly of naval reservists. The light cruiser, HMS Glasgow, was Cradock’s only modern unit. The Admiral flew his flag in Good Hope.

In terms of gunpower, the British armored cruisers were decidedly inferior to Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Good Hope carried 2 x 9.2in guns in single turrets fore and aft on the centerline, and 16 x 6in guns in port and starboard casement mounts. The casements were arranged in pairs with one gun on the upper deck over one gun on the main deck, and the latter were so close to the waterline that they were unusable except in calm weather. Monmouth was armed with 14 x 6in guns, four in twin turrets fore and aft on the centerline and the rest in port and starboard casement mounts, six of which were at main deck level, thus mostly unusable.

Cradock’s squadron was supposed to have been reinforced by HMS Defence, a more modern armored cruiser, but she was retained in the Atlantic, where another German light cruiser was at large, Instead, Cradock was given the elderly pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Canopus. This ship had originally entered service in 1900 and was in reserve when the war broke out. Like Cradock’s armored cruisers, Canopus was recommissioned with a crew largely made up of naval reservists. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, was confident that the old battleship with its 12in guns would be the “citadel” around which Cradock’s squadron would be safe from Spee.

His confidence was misplaced. When Cradock concentrated his squadron at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands, it was found that due to engineering problems, Canopus could not make her design speed of 18.5 knots. Cradock therefore decided to leave her behind and take the rest of his ships around Cape Horn. He sailed on 20 October. At that point he was still under the impression that Defence would join him. But as had been the case with the pursuit of the Goeben in the Mediterranean, a breakdown in communications between the commander afloat and the Admiralty sowed confusion.

In London, Churchill had become preoccupied with the outcry against the First Sea Lord, Price Louis of Battenberg, whose German connections were suspected to have played some tole in the Goeben debacle. He was forced to resign, Admiral of the Fleet Lord “Jackie” Fisher replacing him on 30 October—too late to have any influence over the impending battle off the coast of Chile. Cradock was left with the belief that his orders obliged him to intercept and engage the Ostasiengeschwader “if possible”: a dangerously ambiguous instruction, considering Cradock’s combative nature. Back in London, the Admiralty was unaware that Cradock had proceeded to sea without Canopus, and Churchill later professed to be dumbfounded when he learned that such was the case.

On 31 October, Glasgow called at Coronel on the Chilean coast to obtain news from the British consul there. A German supply ship, also in the harbor, reported the cruiser’s arrival to Spee by radio, and he decided to move his ships to Coronel in hopes of catching Glasgow. For his part, Cradock was hoping to pounce on a German light cruiser whose radio transmissions indicated it was nearby. Neither admiral was aware that that the other side’s main force was in the vicinity.

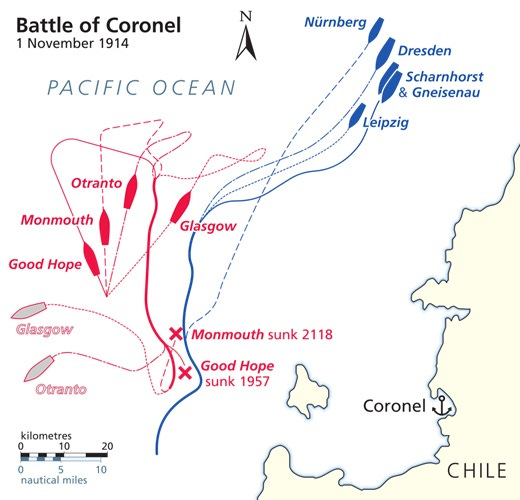

Glasgow left Coronel the next morning to rendezvous with Cradock at noon, some fifty miles west of Coronel. In rough seas, the British ships deployed into line abreast, fifteen miles apart, and commenced a search for the German cruiser believed to be in the area. Their smoke was sighted by the light cruiser Leipzig at quarter past four that afternoon. She was in company with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau; Spee’s other two light cruisers were still some distance behind. Nonetheless, he immediately ordered full speed on a southerly intercepting course.

Five minutes later, Glasgow and the auxiliary cruiser Otranto spotted smoke to the north and soon afterwards three ships became visible. Cradock deduced that they must be the German armored cruisers and ordered his squadron to reverse course. But soon he realized that he’d be unable to outrun the enemy. So he decided to fight, detaching Otranto, which departed the scene at her best speed. Cradock can have had no illusions about the outcome of the imminent battle; it has since been speculated that he hoped at least to damage the German ships.

A few minutes after five p.m., Cradock ordered his ships to concentrate and steer southeast. Probably he intended to close with the enemy while the sun was still high. But Speer turned away, making use of his squadron’s speed advantage to stay outside the range of the British guns. This went on until sunset at ten minutes to seven, whereupon the Spee closed the range to 12,000 yards and opened fire.

The Germans scored almost immediately, hitting Good Hope’s forward 9.2in gun turret and knocking it out of action. Cradock again attempted to close the range and this time managed to get within 6,000 yards of the enemy, but most of his ships’ 6in guns were unusable in the heavy seas, while the German fire became deadly accurate at such close range. In short order both British armored cruisers were ablaze and clearly visible to the German ships, now cloaked in darkness. Monmouth’s guns soon fell silent, and the German armored cruisers concentrated on Good Hope. Cradock’s flagship was still firing and attempting to close the range but by ten minutes to eight her guns too had fallen silent. A few minutes later, Good Hope’s forward magazine exploded. She rolled over and sank, taking all hands with her—unobserved by the Germans, who for some time after the battle assumed that she’d manage to slip away.

Scharnhorst thereupon turned her attention to Monmouth, while Gneisenau reinforced Spee’s light cruisers, which had been exchanging fire with Glasgow. This convinced John Luce, Glasgow’s captain, that there was no point in continuing the fight. His ship had been damaged but could still steam at 24 knots, making good her escape. Before leaving the scene, Glasgow returned briefly to Monmouth, which was slowly sinking but still underway. Her captain informed Luce that if possible, he intended to beach his ship on the Chilean coast. There being nothing more that Glasgow could do, she retired on a southerly course.

Monmouth was finally sunk by the light cruiser Nürnberg, arriving late to the battle. Sighting the British ship, she closed in, offering to accept a surrender. This being declined, Nürnberg opened fire, sending Monmouth to the bottom with all hands. The German victory was complete, brilliant, and stunning. But its sequel was to be a complete reversal of fortune.