A reasonably succinct overview of the warship classes of the Great War navies necessarily involves some degree of generalization. For the most part reference is made to ships of the British and German navies, and it should be understood that other navies did not match them in all respects. The US Navy, for example, had few modern light cruisers of the type employed by the main antagonists in the North Sea. With that caveat, the following account is broadly applicable to the British, German, American, French, Russian, Italian, Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Japanese navies.

This survey is presented in two parts: the first covering major surface warship classes and the second covering submarines, older and minor warships (sloops, gunboats, minelayers, minesweepers, etc.), aircraft carriers and naval auxiliary vessels. Also projected are articles dealing with more specific subjects, e.g. British battleships, German U-boats.

Submarines

The idea of a submersible warship was nothing new—examples from the American Revolution and Civil War can be cited—but only at the dawn of the twentieth century had the relevant technology advanced to a point at which the submarine could be seen as a plausible weapon of naval warfare.

There were two great problems to be overcome before submarines could become effective warships: armament and propulsion. The first was solved by the advent of the self-propelled torpedo. The Whitehead torpedo, developed by a British engineer employed by the Austro-Hungarian firm of Fiume, was successfully demonstrated for the Royal Navy in 1870—raising for the first time the possibility that large warships could be sunk by quite small ones. This led, first, to the development of surface torpedo craft—culminating in the fleet torpedo boat and the destroyer—and finally to the submarine.

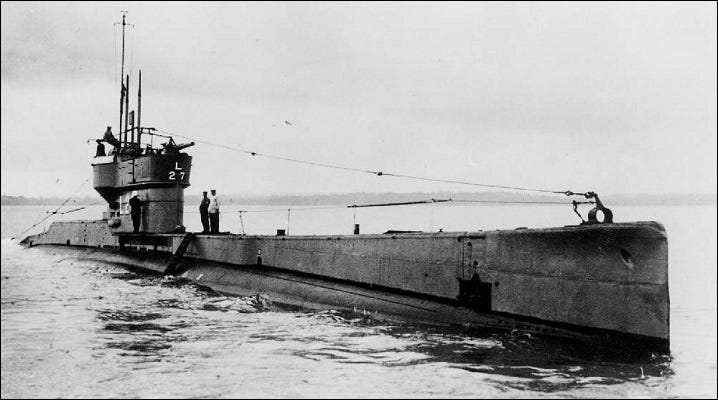

In Britain serious development of the submarine began around 1900. The First Sea Lord, Sir John Fisher, was a man whose mind was always open to new ideas and he embraced the submarine, initially as a defensive vessel for harbors and naval anchorages. If this seems to betray a curious lack of vision, it must be remembered that the submarines of the day were limited in size, hence also in seaworthiness and endurance. But this was to change as the Great War approached. The first three classes of British submarines were rather primitive, but the RN gained valuable experience with them and the boats of the "B" class, ordered in 1904, were good enough to see active service during the war. They had gasoline engines for surface propulsion and a battery-powered electric motor for propulsion when submerged. The gas engine not ideal, however, and in all following classes diesel engines replaced them. The usual armament of these early RN submarines consisted of a pair of bow torpedo tubes, a stern tube, and a deck gun of 3in or 4in caliber.

Wartime submarine development in Britain proceeded by fits and starts, often in reaction to intelligence reports on German submarine policy, but by the end of the war, with the "L-50" class, the RN had evolved a successful design that provided a basis for postwar development. These boats had six bow-mounted 21in torpedo tubes and two 4in guns. Only seven were actually completed, many being cancelled when the war ended, but they remained in service up to the late 1930s.

In Germany the development of the submarine (Unterseeboot or U-boat) received low priority up to 1910. Thereafter the emphasis was on U-boats to support the surface fleet, defending naval bases and undertaking offensive operations in the North Sea and the Baltic. At the beginning of the war the German Navy had twenty U-boats fit for active service, plus another dozen or so working up or under construction.

With the war's outbreak a great expansion of the U-boat program was put in hand, and the need to get many boats into service quickly led to simplified designs. Two types were developed: the torpedo-armed UB and the minelaying UC. These boats were relatively small, being intended for operations in the Baltic, the North Sea, the English Channel and around the British Isles. When the German government decided on a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare in mid-1915 larger boats were required, and the ocean-going M Type was developed. There was also a program of "cruiser" U-boats with heavy gun armament, considered necessary to prosecute anti-commerce warfare in accordance with international law after the unrestricted submarine warfare policy was reversed for diplomatic reasons in March 1916.

When the decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare was made in late 1916 another large program of U-boat construction was undertaken and given absolute priority. Most of these boats were of the UB-48 type: large ocean-going submarines with five torpedo tubes (four bow, one stern) and a 3.4in or 4.1in deck gun.

From 1906 to 1918 the German Navy commissioned 343 U-boats of various classes and types. Those not sunk, lost or scuttled, 175 in number, were allotted to the Allied powers, the US for example receiving seven. A few saw service in the French Navy, but most were expended as targets or scrapped. By the terms of the 1919 Peace Treaty, Germany was prohibited from constructing or operating submarines of any kind.

Sloops, Gunboats and Patrol Craft

Soon after the outbreak of the war, the Royal Navy recognized the need for small warships capable of minesweeping and general duties such as towing, transporting stores and personnel, etc. The result was the “fleet sweeping sloop,” designed to mercantile standards, that could be built by non-specialist shipyards. These ships, of which there were three classes, displaced around 1,200 tons, were about 250 feet in length and had a maximum speed of sixteen knots. Armament was 2 x 12-pounder (3in) guns in the first class and 2 x 4in or 4.7in guns in later classes, plus 1 or 2 x 3-pounder (47mm) antiaircraft guns.

Up to 1917 the fleet sweeping sloops were used mainly for minesweeping, but with the German declaration of unrestricted U-boat warfare they were pressed into service as convoy escorts, proving successful in that role. Many received depth charge racks and various types of antisubmarine mortars

The urgent need for escorts led to the development of the "convoy sloop," similar in size to the sweeping sloops but designed to resemble merchant ships. This, it was hoped, would give them a chance to get within gun range of surfaced U-boats. They had much the same gun armament as earlier sloops plus depth charge racks and antisubmarine mortars.

Many of these sloops were retained in the postwar fleet, and a few even survived to serve in World War Two.

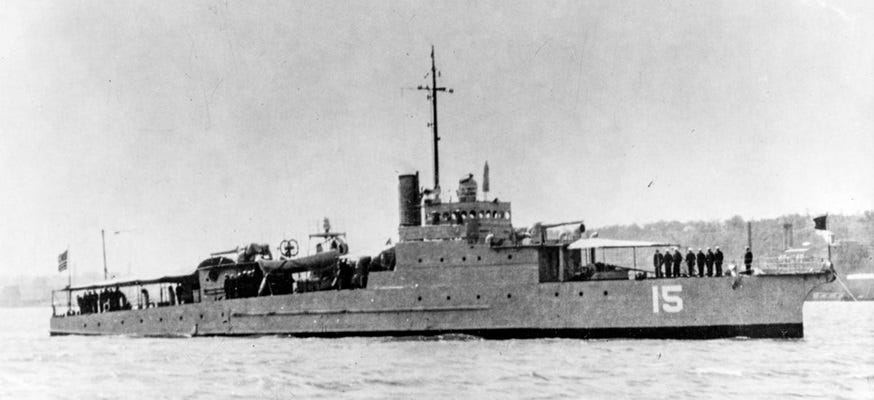

In addition to sloops, the RN operated numerous smaller escort and patrol craft: the P-Boat "utility destroyers," gunboats, and trawlers. Two classes of escort/patrol craft were built for the US Navy in 1917-18: the "Eagle Boat"-class escort, similar to the British P-Boat, and the smaller wooden-hulled "SC"-class submarine chaser.

The German Navy had no equivalent requirement for large numbers of antisubmarine escorts, though its fleet minesweepers (see below) could serve as such. Some of the older German torpedo boats, no longer fit for fleet service, were refitted as patrol vessels, usually with their torpedo tubes removed.

Mine Warfare Craft

There were two types of mine warfare craft: minelayers and minesweepers. The former category embraced a wide range of vessels, from cruisers to submarines. The latter category included fleet or ocean minesweepers like the RN's fleet sweeping sloops (see above), coastal minesweepers, and various smaller minesweeping vessels. Many minesweepers were converted older warships or requisitioned civilian vessels.

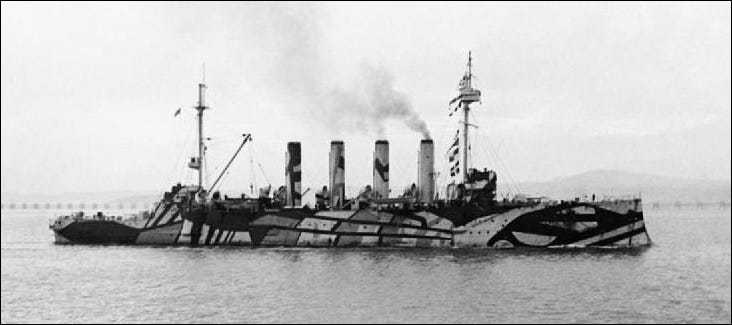

Offensive minelaying, during which enemy forces might be encountered, required either an escort of light cruisers and destroyers or speedy, well-armed ships operating independently. The RN, which had somewhat neglected mine warfare before 1914, mostly relied on older warships and requisitioned merchant ships converted for minelaying. Its margin of superiority over the German Navy enabled escorts to be provided for these ships. The Germans, on the other hand, opted for purpose-built cruiser-minelayers. Two such ships existed in 1914: the minelayers of the "Nautilus" class. They resembled contemporary cruisers but were much smaller and rather lightly armed. To supplement them, the two ships of the "Brummer" class were constructed in 1915-16. These ships were true cruiser-minelayers: fast, well armored, armed with 4 x 5.9in guns and a twin torpedo tube mount. They could carry up to four hundred mines. In addition, many German light cruisers could be fitted to carry and lay mines.

As noted above, minesweepers were both purpose built and conversions of other vessels. Conversions prolonged the useful life of ships judged to be obsolete in their original role. Some of the RN's none-too-successful torpedo gunboats were so converted, as were some of the German Navy's older torpedo boats. Germany's wartime purpose-built fleet minesweepers were well designed and proved very successful. These ships were armed with 2 x 3.4in guns, making them suitable for patrol or escort duties. They could also be employed as light minelayers. Some served postwar with the Reichsmarine (the navy of the Weimar Republic), a few survived to serve in Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine, and their design was replicated with updates for World War Two minesweepers.

Some fifty "Bird"-class minesweepers were built for the US Navy between 1916 and 1919. They were comparable to though slightly smaller than the RN sweeping sloops.

Mine-laying submarines were something of a German specialty, and several classes were built during the Great War. The larger ones could carry up to seventy-two mines; the smaller ones twelve to eighteen mines. The mines were discharged through vertical tubes with the boat submerged.

Aircraft Carriers

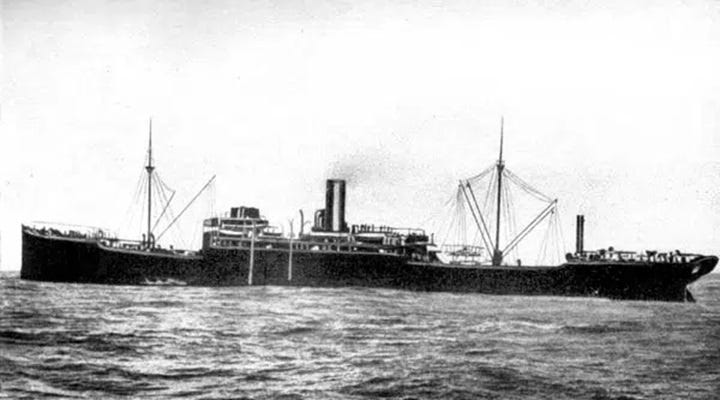

Naval aviation was born during the Great War, with the RN very much in the lead. Prewar experiments with shipboard aircraft led to the construction of HMS Ark Royal, the world's first purpose-built aircraft carrier, which entered service at the end of 1914. The Admiralty purchased the incomplete hull of a bulk grain carrier, specifying such extensive modifications as to take Ark Royal out of the conversion class, and she emerged as an entirely new ship. The forward part of the hull accommodated a large aircraft hangar plus airframe and engine workshops. Aircraft were hoisted from the hangar by a pair of deck-mounted cranes. Ark Royal's aircraft complement included five floatplanes and two landplanes, both of which took off from the forward flight deck. The former could be recovered by crane after landing on the water and taxiing alongside; the latter had to land ashore and be transferred back to the ship by lighter.

Ark Royal was sent to the Dardanelles in February 1915 and there she proved a great success, providing the Allied fleet with much-needed air support. She remained in the Mediterranean for the rest of the war, eventually serving as an aviation depot ship, and was not finally retired until 1946, after service in World War II as HMS Pegasus—having given up her original name in 1934 to a new carrier under construction.

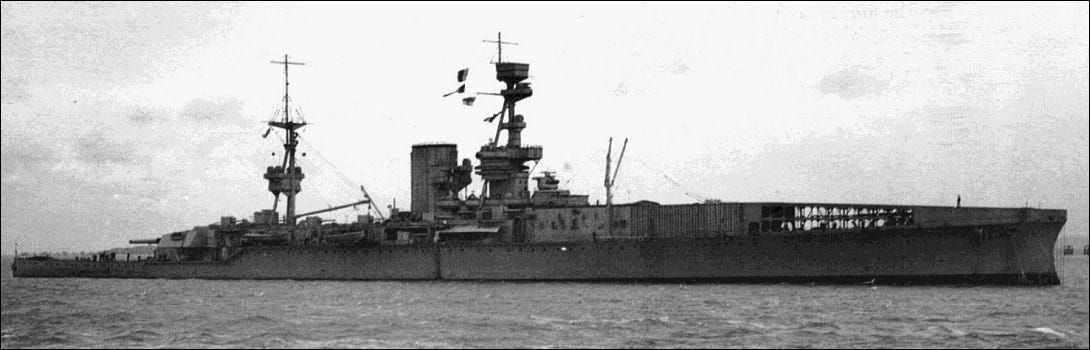

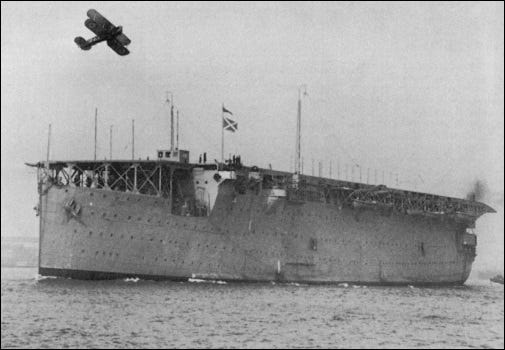

The RN commissioned a number of aircraft carriers and seaplane carriers during the war, mostly conversions. Among them was the "light battlecruiser" HMS Furious, which received a flying-off deck in place of her forward turret while under construction. (see photo at head of article). She was less than satisfactory in this configuration; though aircraft could fly off with no difficulty, it was almost impossible for them to land aboard. Once this was realized the aft gun turret was removed and replaced by a landing deck.

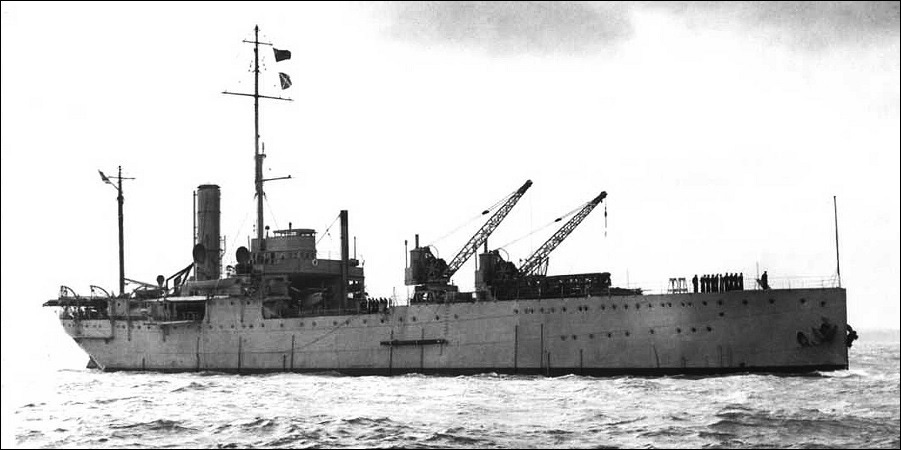

Much better was HMS Argus, built in 1916-18 using the hull of the incomplete passenger liner Conte Rosso, whose construction had been stopped at the beginning of the war. The large hull gave room for a spacious aircraft hangar and a full-length flight deck. The bridge was in the bow and there was a small retractable pilot house forward on the starboard side of the flight deck. Two lifts (elevators) moved aircraft between the hangar and the flight deck. With a maximum sea speed of 20 knots Argus was fast enough to produce the necessary wind-over-deck conditions for flight operations. She could carry some eighteen aircraft; the planned air group was to consist of Sopwith Cuckoo torpedo bombers for a 1919 attack on the German High Seas Fleet. But Argus was not commissioned until the autumn of 1918, too late to play a part in the war. Subsequently, however, she gave valuable service as a trials and training carrier, proving the concept of the through-deck aircraft carrier. Argus survived to serve with distinction in World War Two as an operational carrier, a training carrier and finally as an aircraft transport. She was decommissioned in early 1945 and was sold for scrapping in 1946.

Naval Auxiliary Vessels

Large numbers of civilian vessels were requisitioned by the navies of the major powers, to serve in a wide variety of roles. At the beginning of the war numerous passenger liners were taken over for service as armed merchant cruisers and escorts. Other merchant ships were pressed into service as destroyer and submarine depot ships, minelayers, minesweeper depot ships, supply ships, etc. Smaller merchant ships became patrol vessels, dispatch vessels or minesweepers. The Royal Navy employed a large number of cargo ships as submarine decoy vessels—Q-Ships as they were codenamed. The Q-Ships carried their guns concealed behind false bulkheads and their crews were trained to fake an abandon ship routine, the idea being to lure U-boats into an ambush.

The German Navy commissioned several requisitioned merchant ships as commerce-raiding cruisers. Their guns, usually of 5.9in caliber, were mounted in concealed positions and the ships masqueraded as friendly or neutral vessels to get within range of their quarry. Thereupon the German naval ensign was hoisted and a shot was fired across the target vessel's bow. Usually the enemy crew was taken off and made prisoner and the ship was then sunk, but sometimes a prize crew was put aboard. Most of the vessels selected for employment as commerce raiders were modern cargo ships. But the most famous of them was the full-rigged sailing ship Seealder ("Sea Eagle"). Built in 1878, she was of British origin and was captured by a German U-Boat in 1915. An imaginative junior naval officer convinced his superiors to employ the ship as a commerce raider, and the idea proved most successful. Under her captain, Count Felix von Luckner, Seealder captured sixteen Allied merchant ships before being wrecked off an island in the Pacific in 1917.

Most requisitioned merchant vessels were restored to their owners after the war and resumed their civil careers.

Older warships also ended their careers serving in auxiliary roles. Several German pre-dreadnought battleships, for example, were converted into minesweeper depot ships. Other old warships served as harbor guardships, training ships, accommodation ships, etc. Almost all such ships were decommissioned and sold for scrapping after the war.

One point that comes through in your column - the willingness of navies to explore/experiment with new designs.

The U.S. Navy tried that recently with Littoral Combat Ships (LCS), creating a modular design and even trying two different hull designs.

Bravo.

But both the design and the execution were flawed.

Unfortunately, Washington seems determined to violate Clausewitz's dictum ("Never reinforce defeat"), and continues to build them.