Part Seventeen: Round Two in the East (2)

(For clarity, German and Austro-Hungarian formations are rendered in italics.)

The unsatisfactory outcome of the First Battle of the Vistula might have been expected to pass the initiative on Eastern Front from Germany and Austria-Hungary to Russia. The former’s drive on Warsaw had been repulsed with heavy casualties; the latter had been forced to give back all its earlier gains, with the key Galician fortress of Przemysl once more besieged. It was, or should have been, a dangerous moment for the Central Powers.

But for various reasons the Russian victory, though real enough, produced no decisive results. The problem for the Russians was, as it had been since the beginning of the war, a divided command. Southwest Front (General of Artillery Nikolay Ivanov) was drawn in the direction of the Austrians, now defending the line of the San River. Northwest Front (General of Infantry Nikolai Ruzski) was focused on East Prussia, and its commander worried constantly about a renewed German drive on Warsaw. The situation was aggravated by the fact that the dividing line between the two fronts ran through the Polish salient. From Stavka, the high command, came a stream of messages from the Commander-in-Chief, Grand Duke Nicholas, pointing out that success in East Prussia and along the San were the essential preliminaries to a drive on Berlin. Since everybody knew this, the Grand Duke’s admonitions cannot be said to have clarified the situation.

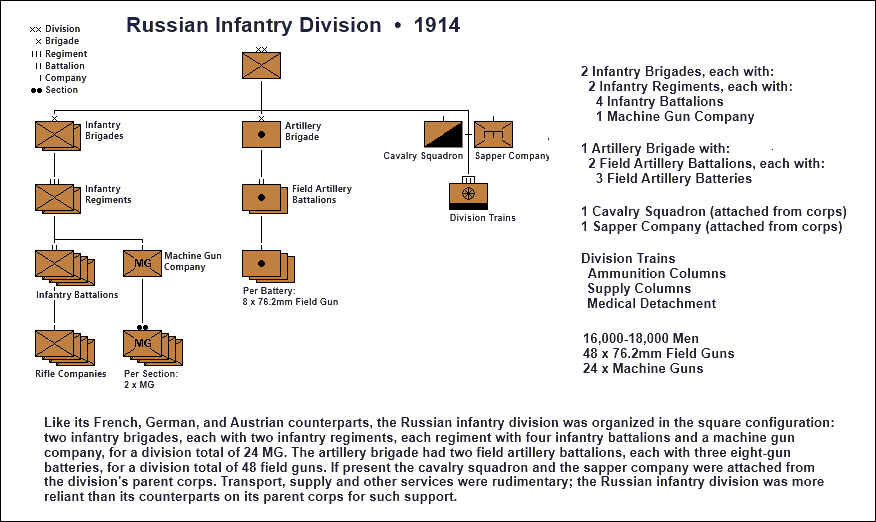

The operations of the Russian armies were thus fitful and uncertain, distracted by contradictory orders and aggravated by the usual supply problems. It was at this time that the shell shortage, later to be cited as the excuse for so many failures and defeats, began to manifest itself. By mid-November, the average daily provision of ammunition for the 76.2mm field gun was a mere ninety rounds.

Finally, however, a plan for the invasion of Germany was pieced together. It was to be carried out by Second Army (General of Cavalry Sergei Sheydeman) north of Lodz, Fifth Army (General of Cavalry Pavel Plehve) south of Lodz, and Fourth Army (transferred from Southwest Front; General of Infantry Alexei Evert) farther south—all three under the command of Ruzski. Southwest Front was left, from north to south, with Ninth, Third and Eighth Armies to deal with the Austrians, Ivanov protesting that without Fourth Army there was little he could do.

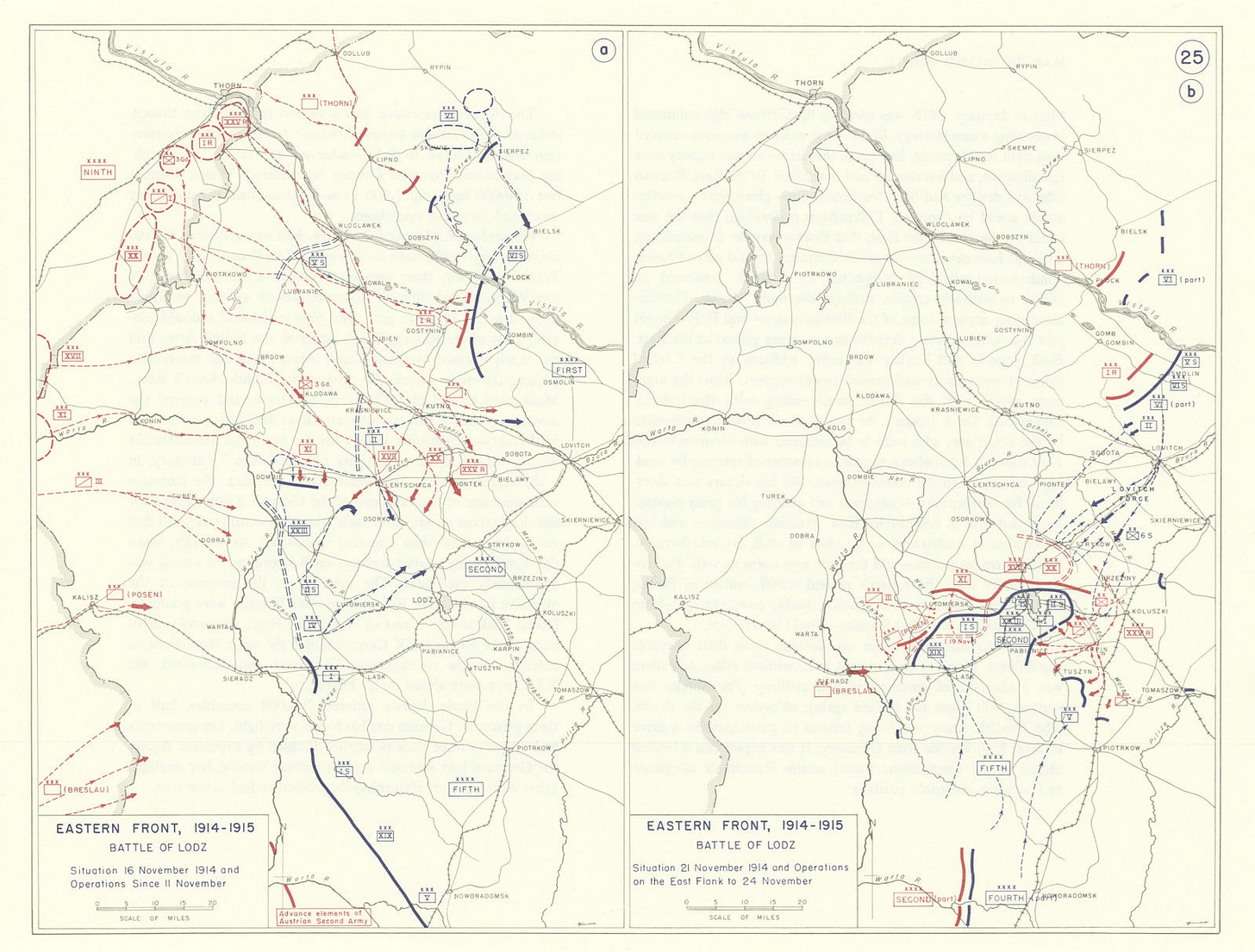

Neither Ruzski nor Stavka seem to have considered what the Germans might do; it was blithely assumed that the enemy would passively await the advance of the Russian steamroller. But Ludendorff was not content to stand on the defensive. By this time Hindenburg had been made “Supreme Commander of All German Forces in the East” (Oberbefehlshaber der gesamten Deutschen Streitkräfte im Osten or Ober Ost) with Ludendorff as chief of staff. German intelligence had broken the Russian radio code, so that Ober Ost had good information regarding Russian intentions and forces. Ludendorff decided to forestall their offensive by striking the right flank of Second Army. For that purpose, Ninth Army (General of Cavalry August von Mackensen) was redeployed from its position near Cracow to Thorn. This move involved some ten divisions and was completed in six days (4-10 November)—a testament to the efficiency of German staff work. Around Cracow, Austrian Second Army was brought up from the Carpathians to replace Ninth Army.

The right flank of Second Army was supposedly covered by First Army (General of Cavalry Paul von Rennenkampf) to its north. But this army was spread along a long front covering the southern border of East Prussia, leaving Rennenkampf with insufficient forces on his left. This was doubly unfortunate since the left-wing corps of First Army, V Siberian Corps (Lieutenant-General Leonty Sidorin) was in an isolated position south of the Vistula River. Sidorin’s corps consisted of low-quality reserve divisions, was short of artillery, and had neglected to prepare adequate defensive positions. Thus when the Germans attacked with three corps on 11 November, V Siberian Corps promptly collapsed. The Russian artillery abandoned the infantry to its fate, two-thirds of whom were captured, and the remnants of the corps fell back along the Vistula, opening a thirty-mile gap in the Russian line.

Ruzski at first assumed that the German attack was a feint by two or three divisions that had met unexpected success against second-rate troops. When Rennenkampf requested permission to move his VI Siberian Corps to parry the German blow, the Northwest Front commander refused it. Believing that the main German force was farther south, he instead ordered the invasion of Germany to commence.

Thanks to this ill-advised order, when Ninth Army commenced its attack on 14 November four of Second Army’s five corps had already advanced some distance to the west. The Germans promptly fell on the fifth, right-flank, corps of Second Army and routed it. This blow stopped both Second and Fifth Armies in their tracks. Prudently, they turned about and fell back on their main supply base, the city of Lodz. Two days of hard marching brought seven Russian corps into line covering Lodz by the time that the Germans arrived.

Neither the Russian nor the German command had a clear picture of the situation at this point. Ruzski and Stavka failed to appreciate that their armies had suffered a tactical reverse and demanded a renewal of the offensive. For their part, Hindenburg and Ludendorff imagined that they’d scored a great strategic victory, with the Russians in full retreat, and they ordered Ninth Army to cut the enemy off by capturing Lodz.

Fortunately for the Russians, either command confusion prevented Ruzski’s orders from reaching the armies, or the commanders on the spot simply disregarded them, for a renewed drive to the west would have played into the hands of the Germans. Instead, it was Ninth Army that found itself in a dangerous position, facing a numerically superior enemy force that had the advantage of operating close to its main base of supply.

The German attempt to envelop Lodz was countered by Plehve’s Fifth Army, counterattacking in bitter winter weather on 18 November. Mackensen, though he tried to keep the two corps of his right flank on the move, made little progress by 20 November. And meanwhile, a force detached from First Army was marching southwest toward the town of Bielawy in an attempt to close the gap between it and Second Army. In its path stood a single German cavalry regiment.

When the First Army detachment reached Bielawy, XXV Reserve Corps (Lieutenant-General Reinhard von Scheffer-Boyadel) and III Cavalry Corps (Lieutenant-General Manfred von Richthofen) on Ninth Army’s left flank, were effectively isolated, their routes of retreat blocked. Once the Russians realized that they had some 11,000 German troops plus 3,000 wounded surrounded, they ordered trains forward to transport the anticipated bag of prisoners to the rear.

But the sequel was a convincing demonstration of the German Army’s superior discipline and training. A Russian reserve corps similarly isolated would have gone to pieces, but Scheffer-Boyadel, who’d been called out of retirement to command XXV Reserve Corps, rallied his frozen, hungry men, formed them into three columns, and led them northwest toward Bielawy while Richthofen’s cavalry covered their rear. The left-hand column arrived at Bielawy on 24 November after an all-night march and launched an immediate attack, taking the town’s garrison, 6th Siberian Rifle Division, by surprise. The division’s commander suffered a nervous breakdown and most of his men were taken prisoner. The other two columns broke through the Russian line west of Bielawy, clearing the way for XXV Reserve Corps and III Cavalry Corps to reestablish touch with the rest of Ninth Army northwest of Lodz. The Germans brought all their wounded out with them—and even 16,000 Russian prisoners!

This notable feat of arms was facilitated by bad weather and the usual breakdowns of command on the Russian side. Neither Ruzski nor his army commanders could frame a clear picture of the situation, and their orders only sowed more confusion. By this time, Second and Fifth Armies had suffered more than 100,000 casualties. Munitions, rifles, even boots for the men were running short. It was obvious that the invasion of Germany could not now take place, and that the armies must go back to a more defensible line along the Vistula River.

This proposal, however, met with protests from Ivanov, the Southwest Front commander. He wanted to go on the offensive against the Austrians; Northwest Front must therefore stay where it was, covering Southwest Front’s northern flank. The renewed dispute between the “southerners” and the “northerners” was finally settled by the enemy. German pressure compelled the Russians to give up Lodz; farther south, the Austrians recovered and even advanced some distance.

On the German side, Ober Ost represented the Battle of Lodz as a great strategic victory and used it to pressure Falkenhayn, the Chief of the OHL, into providing additional reinforcements to the number of four corps. He did so reluctantly, believing as he did that the west, not the east, was the decisive theater of war. But the failure of the German attempt to break through at Ypres in Belgium and the shaky condition of the Astro-Hungarian Army took some of the wind out of the Chief of the OHL’s sails, and for the moment Hindenburg and Ludendorff had their way. Their renewed offensive made little progress east of Lodz, however, and losses were heavy. By the end of the year the Eastern Front had stabilized and the prospect of a decisive conclusion of the campaign seemed as far off as ever.