Part Fourteen: Opening Round in the West (5)

(For clarity, German units are rendered in italics.)

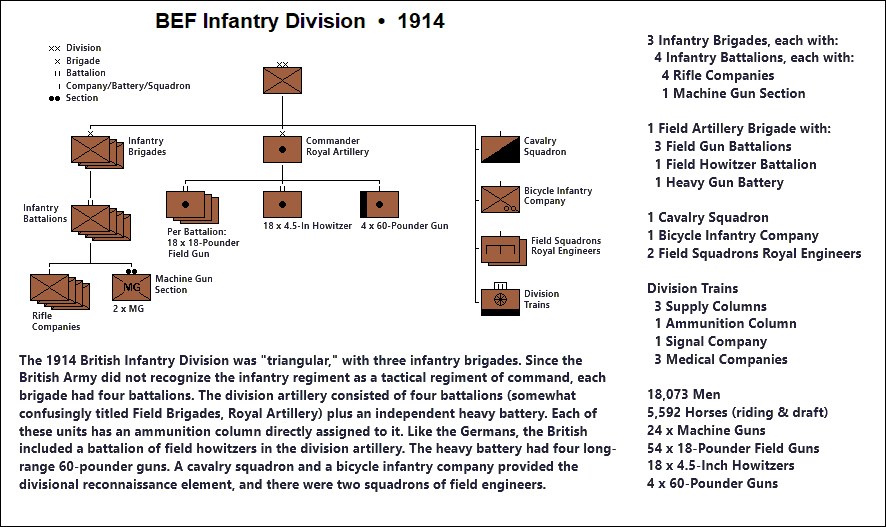

The 1914 Battle of Flanders was actually a series of engagements in two areas. Along the fifteen-mile stretch of the Yser River between the Channel coast and the vicinity of the village of Oudecapelle, where the river bends west, the Belgian Army, a French infantry division, and six battalions of French marines fought to stop the advance of German Fourth Army, while in the vicinity of the town of Ypres the British Expeditionary Force (seven infantry divisions and three cavalry divisions) opposed the advance of Fourth Army’s left wing and the bulk of Sixth Army. Between the Belgians and the BEF stood the newly constituted French Eighth Army (twelve infantry divisions and eight cavalry divisions under General Victor d'Urbal), formerly the Détachement d'armée de Belgique (Army Detachment in Belgium).

After the Battle of the Marne the BEF had been transferred from the Paris area to Flanders, this to position it closer to its bases on the Channel coast. As things turned out the British Army would fight in Flanders throughout the war, undergoing a long ordeal that has passed into legend. Nowhere else on the Western Front, save at Verdun in 1916, was the essence of trench warfare so thoroughly distilled.

The linked First Battle of Ypres and Battle of the Yser raged from mid-October to late November 1914: a month and a half in which the original British Expeditionary Force was effectively wiped out. Total British casualties from August to November 1914 were not far short of 90,000 killed, wounded, and missing in action: nine-tenths of the force initially sent to France. Some 60,000 of those casualties were inflicted during First Ypres. For the British, the battle thus came to symbolize the peculiar horrors of trench warfare on the Western Front: the rain, the mud, the misery, the unceasing artillery bombardments, the strain, the deadly fatigue, the ever-present shadow of death.

It has been said that the virtues and qualities of the Old Contemptibles—the soldiers of the prewar British Army—rendered inevitable their martyrdom in Flanders. Regimental loyalty, inarticulate yet deep patriotism, unthinking courage and sheer stubbornness kept them positioned in their waterlogged shell holes and rudimentary trenches, day after day, week after week, in the face of violent German attacks that stretched the defense to the breaking point. In the end the line held—but the price paid was intolerably high. Henceforward a new and different British Army would fight the war: Territorials, Kitchener volunteers, and conscripts stiffened by the handful of Old Contemptibles who'd survived the war’s opening round.

The First Battle of Ypres unfolded in five stages. As it redeployed to Flanders, the BEF (Field Marshal Sir John French) clashed with German Fourth Army (Duke Albrecht of Württemberg) and Sixth Army (Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria) between 19 and 21 October. Then followed the Battle of Langemarck (21-26 October), the Battle of Gheluvelt (29–31 October), the last big German push from 5 to 13 November, and finally a series of minor clashes that gradually petered out by the end of November.

As mentioned above, First Ypres was fought concurrently with the Battle of the Yser, where the Belgian Army (King Albert) and its attached French units opposed the advance of German Fourth Army along the Yser River, terminating on the Channel coast. The French General Ferdinand Foch coordinated Allied operations and though he had no formal power of command over the Belgians and British, he was able to secure their cooperation. His management of the Allied reserves—mainly French—had a major impact on the outcome of the linked battles along the Yser and around Ypres.

The Encounter Battle

First Ypres commenced when advancing German troops made contact with units of the BEF moving into the Ypres area. Both sides were intent on an attack to roll up the enemy’s flak and advance along the Channel coast. The fighting took place a little east and south of the town of Ypres, both sides seeking to advance. The BEF made some initial progress but was stopped by German counterattacks, both sides suffering heavy casualties. The British then went over to the defensive while the Germans regrouped for a deliberate attack.

General Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the OHL and de facto German commander-in-chief, sought to deliver a decisive stroke down the Channel coast, capturing the ports that were so important to the BEF. For this operation he reorganized his forces, setting up a new Fourth Army on the German right flank to which were assigned eight of the twelve new reserve divisions raised in August and now judged ready for action. Fourth Army’s mission was twofold: (1) to cross the Yser River, annihilating the Belgian Army and driving along the Channel coast, and (2) to crush the BEF around the town of Ypres, capturing that town and rolling up the Allied left flank. Farther south, Sixth Army would attack with the mission of protecting Fourth Army’s left flank.

The Battle of Langemarck

The German offensive was launched on 21 October and the fighting came to center around the town of Langemarck, northeast of Ypres, where XXVI Reserve Corps of Fourth Army, attacking with two divisions, sought to smash the BEF’s IV Corps (one infantry division, one cavalry division and an attached French territorial infantry division) on the BEF’s left flank. The German divisions included a large number of young volunteers, enlisted at the start of the war in August, sketchily trained and poorly equipped. Attacking in dense formation, the Germans were repeatedly savaged by the defenders’ rifle, machine gun and artillery fire. But the British too suffered heavily and the fighting swayed back and forth until the exhausted Germans broke off their attacks. The battle entered into legend on the German side as the Kindermord (Massacre of the Innocents)—a reference to the heavy casualties suffered by the young volunteers.

Subsequently the German offensive was renewed farther south, along the Menin Road (25-26 October). Here the British defenses fell apart, but reserves were brought forward and managed to plug the gap, preventing a German breakthrough.

The Battle of Gheluvelt

By 26 October, Falkenhayn recognized that his attacks so far had failed. He therefore ordered Fourth Army and Sixth Army to revert to an active defense pending the assembly of a new attack group. This was Armeegruppe Fabeck (General of Infantry Max von Fabeck), a temporary formation consisting of three corps with eight divisions. It was to be inserted between Fourth Army and Sixth Army with the mission of attacking toward Ypres. Armeegruppe Fabeck would be supported by XXVII Reserve Corps of Fourth Army, attacking toward the Gheluvelt crossroads. Sixth Army was to stand on the defensive, giving up a proportion of its heavy artillery to Armeegruppe Fabeck.

The new German offensive commenced on 29 October, with XXVII Reserve Corps advancing against the BEF’s I Corps north of the Menin Road. Fog aided the Germans, who managed to gain the Gheluvelt crossroads by nightfall, capturing more than 600 British troops in the process. Farther south, Armeegruppe Fabeck fell on I Corp’s right flank and upon the BEF’s Cavalry Corps, fighting as infantry. Here the German attack penetrated to within two miles of Ypres itself and once again the battle seesawed back and forth. The timely arrival of three French battalions and the intervention of “Bulfin’s Force,” a formation improvised from a miscellany of British service troops and stragglers, just barely prevented a breakthrough. But the BEF had no more reserves and the situation looked desperate, Sir John French believing that his army faced total defeat. The Germans had also suffered heavily, however, and after a breakthrough at Gheluvelt on 31 October was contained by a British counterattack, the battle petered out.

The Final German Push

Twice now the Germans had come close to rolling up the Allied line in Flanders and Falkenhayn was determined to try again. This time, however, his objective was more modest: merely to capture Ypres and Mount Kemmel, thus compelling the British to abandon the Ypres salient. But by now both sides were close to exhaustion. Fourth Army’s corps had suffered up to 70% casualties at Langemarck; Armeegruppe Fabeck had lost over 17,000 men in five days of fighting. As for the BEF, it was being bled white. Of its eighty-four infantry battalions, each originally 1,000 men strong, seventy-five now mustered fewer than three hundred men—in some cases fewer than one hundred. Such replacements as arrived in France came nowhere close to covering the losses suffered. Help did come in the form of French XVI Corps, which backstopped the BEF’s hard-pressed Cavalry Corps. The French also conducted attacks farther north in support of the BEF’s I Corps, which by now mustered fewer than 10,000 men—considerably less than the strength of a single infantry division.

General Foch, coordinating the defense of the Allied left flank, planned an attack by Eighth Army toward Langemarck and Messines, to commence on 6 November. The idea was to take pressure off the BEF by expanding the Ypres salient, but German attacks on the flanks of the salient, commencing on 5 November, derailed his plan. On 9 November, the Germans drove back the French and Belgians north of Gheluvelt and on 10 November the main German attack was delivered by Fourth Army, Sixth Army and Armeegruppe Fabeck with thirteen divisions. The attackers broke through in several sectors including the vital Menin Road, and once again it looked as though the British defense would collapse. But heavy casualties, lack of reserves and sheer exhaustion combined to stall the Germans when they seemed close to victory, and the British were able to restore their line.

The Battle Subsides

Mutual exhaustion and the onset of cold weather brought major operations in Flanders to an end after 13 November. Along the Yser River, where the Belgians had opened the sluice gates controlling the drainage system, flooding low-lying areas, both sides became paralyzed. And though the British remained in possession of Ypres, the prize was a dubious one. Their line in the vicinity of the town constituted a dangerously narrow salient projecting into German-held territory, exposed to observation and fire from front and flanks. That the Germans occupied most of the high ground in the area only worsened British problems. But having expended so many lives to prevent the enemy from capturing the town, the BEF’s commanders could not persuade themselves that it would be better to evacuate the salient. Instead they ordered their troops to dig in—ensuring that Ypres would become a name of ill omen in British military annals.

Analysis of the Battle

It may seem inexplicable that so many troops, concentrated in a small area like Belgian Flanders, locked in a month and a half of violent combat, produced nothing but stalemate. But it was precisely that concentration of numbers that made stalemate inevitable. First Ypres/Yser demonstrated with crystal clarity that the defense enjoyed a decisive advantage over the attack. Carl von Clausewitz had preached that defense is the stronger form of war. In 1914, thanks to the Industrial Revolution with its attendant political, social, and cultural fallout, the superiority of the defense in war was maximized. This superiority was distilled into one deadly element: firepower. The rifles, machine guns and artillery supplied to the armies by industry were orders of magnitude more effective and deadly than anything seen on the battlefield since the dawn of history. And this superiority benefited the defenders far more than the attackers—particularly when the former occupied field fortifications. Even a crude hole in the ground greatly enhanced the survivability, hence the effectiveness, of a defending rifleman. And if that hole sheltered a machine gun and its crew, troops attacking in dense formations could be shot down in droves.

Inevitably, therefore, the shell holes and ditches from which the defenders fought the First Battle of Ypres were rapidly transformed into complex entrenched positions, not just in Flanders but all along the Western Front. Protected by dense belts of barbed wire and backstopped by artillery, these trench defenses were, if not absolutely impregnable, extremely difficult to attack. So began the search for some tactical solution to the trench deadlock and the obvious one seemed to be more of what had produced it in the first place: firepower. The generals assured one another and their political masters that with enough guns and shells, the enemy’s defenses could be battered down—demolished like a condemned building. Much blood was to be spent demonstrating the simplistic falsity of this idea.

Of the senior commanders on both sides, it was Erich von Falkenhayn who drew the correct lessons from the Battle of Flanders. He was now convinced that the strategy pursued so far by Germany—Vernichtungsstrategie or annihilation of the enemy—could not succeed. Germany, he perceived, lacked the strength to score a decisive victory over any of her foes. While recognizing that in many respects Russia— economically backward, internally unstable, its leaders fearful of revolution—was the weak link in the coalition confronting Germany, he doubted so large a country could be vanquished by the forces that Germany and Austria-Hungary were able to muster on the Eastern Front. Yet no less than his predecessor, Falkenhayn regarded the Western Front as the main theater of war. He therefore reverted to Ermattungsstrategie, exhaustion of the enemy, a strategy of attrition that would reach its culminating point in the Battle of Verdun.