When asked what he would do in the event of war if the British Army made a landing on Germany’s North Sea coast, Otto von Bismarck replied, “I would send for the police.” And in 1914, with war in sight, Kaiser Wilhelm II sneered that Britain had “a contemptible little army.”

It was true enough that compared with those of the other major European powers, Britain’s army was extraordinarily small. In 1914 the British Regular Army embodied only 270,000 active soldiers, half of them stationed overseas in the colonies. The Army’s reserve amounted to 210,000 men, just sufficient to bring units up to wartime strength and replace the first losses. The Army was backed up by the Territorial Force, 246,000 strong. This was a part-time reserve organization, somewhat analogous to the US National Guard; its members bore no obligation for overseas service. Both the Regular Army and the Territorial Force were manned by volunteers. Despite much argument and pressure from some senior soldiers, Lord Roberts prominent among them, successive British governments had balked at the imposition of conscription.

But within the limits imposed by politics and tradition, much progress had been made by military reformers since the days of Rudyard Kipling’s Barrack-Room Ballads, his imperishable pen portrait of what George Orwell called the pre-machine-gun army. “From the body of Kipling’s early work,” he wrote:

[T]here does seem to emerge a vivid and not seriously misleading picture of the old pre-machine-gun army—the sweltering barracks in Gibraltar or Lucknow, the red coats, the pipeclayed belts and the pillbox hats, the beer, the fights, the floggings, hangings and crucifixions, the bugle-calls, the smell of oats and horsepiss, the bellowing sergeants with foot-long moustaches, the bloody skirmishes, invariably mismanaged, the crowded troopships, the cholera-stricken camps, the “native” concubines, the ultimate death in the workhouse. It is a crude, vulgar picture, in which a patriotic music-hall turn seems to have got mixed up with one of Zola's gorier passages, but from it future generations will be able to gather some idea of what a long-term volunteer army was like.

By 1914, however, “Mr. Kipling’s Army” was no more. The British Army that took the field in 1914 was small, but it was a modern, well-trained, well-armed force. The unofficial alliance with France—the Entente Cordiale—envisioned that in the event of war British troops would go to the assistance of the French Army. To make this possible the War Office under Richard Burdon Haldane, Secretary of State for War from 1905 to 1912, embarked upon a far-reaching modernization program. The Regular Army in the United Kingdom was reorganized as an expeditionary force of six infantry divisions, one heavy cavalry division and two light cavalry brigades with appropriate headquarters and support services, to be mobilized and transported to France within three weeks. The Haldane reforms thus introduced a permanent divisional organization for the Regular Army. They also created the Territorial Force by amalgamating the old Militia and Volunteer organizations to form fourteen infantry divisions and fourteen cavalry brigades for home defense. New training manuals were published and the Army’s support system was rationalized. Finally in 1909 an Imperial General Staff was created. Its tasks included war planning, supervision of military education and training, and military coordination with the self-governing overseas Dominions.

The Haldane program was the culmination of a long and fitful process that had dragged an often-reluctant Army into the modern age. Most significant among earlier reforms was the introduction of short service in 1872, replacing twenty-one-year regular enlistment for other ranks. After five or six years with the Regular Army, short-service officers and other ranks were released to civilian life with a liability for annual training and recall to active duty in time of war. Short service expanded the pool of potential recruits, enabled a modest reserve of trained men to be built up, and raised the overall quality of the Army. The British soldier of 1914 was better educated, better trained and healthier than the “old sweats” of Kipling’s poetry. He was also much better armed and equipped. Indeed, the six British infantry divisions that took the field in August 1914 were probably superior to those of all the other belligerents.

Many of the BEF’s officers and men were combat veterans with considerable experience of colonial warfare. Infantry training emphasized marksmanship and the British soldier was unequaled in his ability to deliver rapid, accurate rifle fire. But these advantages were to some extent offset by a lack of experience at higher echelons of command. No British general officer on active duty in 1914 had ever held wartime command of anything larger than a brigade. Nor did the new Imperial General Staff stand comparison in terms of prestige or professionalism with the German Army’s Great General Staff (Großgeneralstab).

Thus while the BEF had a modern command structure with an army headquarters over two corps headquarters, each of the latter controlling three infantry divisions, senior commanders had only a theoretical knowledge of their responsibilities. Trained staff officers and technical experts were also in short supply, a deficiency that was to become critical as the Army began to expand.

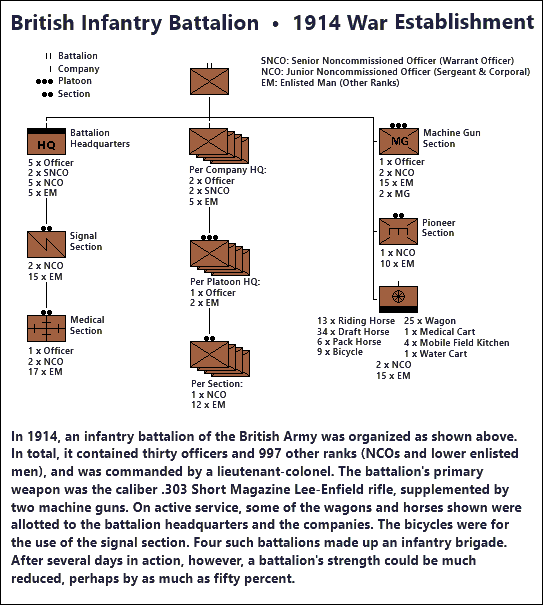

In terms of armament the 1914 BEF was well provided for. The standard rifle was the caliber .303 Short Magazine Lee Enfield, the best weapon of its type in 1914. The SMLE was backed up by the caliber .303 Maxim machine gun, of which each infantry division had 24. The division artillery was powerful, with fifty-four 18-pounder field guns backed up by eighteen 4.5-inch howitzers and four heavy long-range 60-pounder guns. The cavalry was also armed with the SMLE and the Maxim MG—which proved far more effective in combat than the swords and lances that the troopers still carried.

The British soldier’s appearance had also been revolutionized, with the Army’s old colored uniforms relegated to occasions of ceremony. They were replaced by the 1902 Pattern Service Dress in a shade of brown called khaki drab. (Khaki is a Hindustani word meaning dusty and it was in India that such uniforms first began to be worn.) The leather belts and ammunition pouches of the infantry had been replaced in 1908 by cloth webbing equipment of a type originally developed by the American Mills Equipment Company. By the standard of the day both uniform and webbing equipment were well designed and practical.

But though much had changed, the roots of tradition struck deep—and the regimental system, an institution unique to the British Army, was the primary bastion of tradition. In the infantry, the regiment as such was not a combat unit. Infantry regiments of the line consisted of a regimental depot, responsible for recruiting and training, and, usually, two battalions, one in the UK and one serving overseas. Line infantry regiments bore a territorial identity, for instance the Royal Hampshire Regiment, and recruited in that area. The cavalry, artillery and the Guards were differently organized but for them as well the regimental mystique was a living force. The regiment was the embodiment of the soldier's corporate identity, the focus of his loyalty and pride. He wore his regiment’s distinctive badges, perpetuated its peculiar traditions and remembered its history, which often stretched back to the seventeenth century. The senior infantry regiment, the Royal Scots, notoriously proud of its ancient lineage, bore the nickname “Pontius Pilate’s Bodyguard.” Traditional friendships and rivalries between regiments were long remembered.

Certain regiments—the cavalry, the Guards, the Royal Horse Artillery, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps—were socially exclusive, and officers without a substantial private income found it difficult to serve in them. Others, colloquially known as “younger sons’ regiments,” were less pretentious. But each one was unique. Even with khaki service dress the soldiers of the Rifle Brigade continued to wear their traditional black buttons. And for Highland regiments, the khaki uniform was modified to permit the kilt to be worn.

But though it undoubtedly fostered esprit de corps, the regimental system also bred a certain parochialism of outlook incompatible with the demands of modern war. New and novel organizations such as the Tank Corps tended to be looked upon askance by officers and men of distinguished old regiments whose colors bore battle honors from the Seven Years War, the Peninsula, and Waterloo. Nor was the Regular Army enamored of the civilians in uniform who filled the ranks as the war dragged on. A good deal of snobbery greeted temporary officers of undistinguished social background when they began to appear in regimental messes after 1914. By then, however, there were few members of the 1914 BEF still serving. All too many of the Old Contemptibles—as they’d christened themselves with typically self-depreciating humor—had found muddy graves in the vicinity of an obscure Belgian town named Ypres.