Part Two: The Armies of 1914

At the beginning of the Great War the armies of the major belligerents were organized in a standardized, broadly similar manner. First came the numbered field armies, consisting of a variable number of corps. The German Army in the west, for example, was organized into seven field armies, each controlling two to four corps depending on the tasks allotted to them. The corps was the basic tactical formation; it consisted of two or three infantry divisions plus various corps troops: usually a medium artillery regiment, a cavalry regiment, a pioneer (combat engineer) battalion, and various supply columns. The total strength of a corps was 70,000 to 80,000 men. Cavalry corps, though similar in structure, were substantially smaller.

Except in the British Army, infantry divisions were “square divisions,” so called because they embodied two brigades, each of two infantry regiments, each regiment with three or four battalions. The infantry divisions of the British Army (which did not recognize the regiment as a tactical echelon of command) were “triangular” with three brigades of four battalions each. The division artillery usually consisted of a brigade of two regiments with twenty-four to fifty-six field guns and howitzers. Divisions also included a reconnaissance element—a horse cavalry regiment or squadron—and the division trains (supply and ammunition columns, medical and veterinary units, signals detachments, bridging train, etc.).

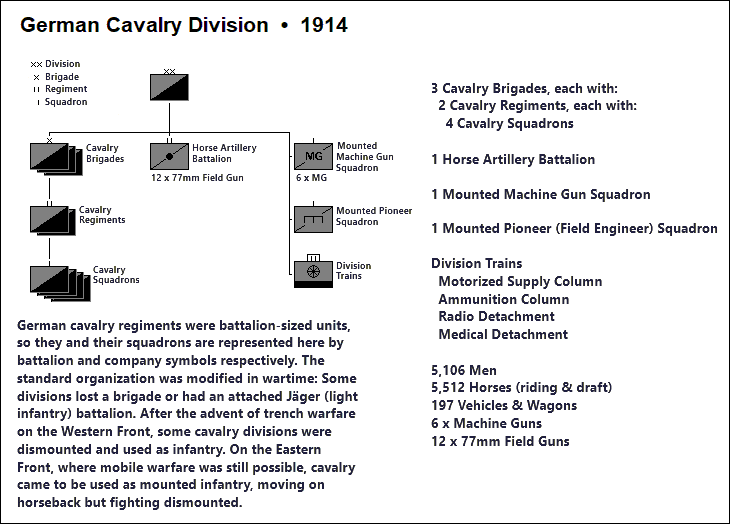

By modern standards, the trains units allotted to the division were scanty, such assets being mostly concentrated at corps level. Though a few motor vehicles were present, most transport was horse drawn. The total strength of a 1914 infantry division was 16,000 to 20,000 men, depending on nationality. Cavalry divisions had a similar organization but a much lower strength: usually 8,000-10,000 men and twelve to twenty-four guns.

Field armies and corps sometimes had aviation squadrons attached, usually with six or eight airplanes, unarmed. Many commanders viewed these air units with skepticism, doubting their military value. But in the 1914 campaigns the airplane proved its worth, operating much more effectively than cavalry in the reconnaissance role. It was a French airplane, for instance, which spotted and reported "Kluck's turn," the redirection of the German Army's right wing that led to the Battle of the Marne.

The field armies of the belligerents embodied the divisions of the active army plus the first-line reserve divisions. The active divisions, consisting of long-service professional soldiers and the current intake of conscripts, were maintained in peacetime at two-thirds to full war strength. On mobilization, they absorbed such recently trained reservists as were necessary to complete their organization. The reserve divisions, usually maintained in peacetime as cadres only, were brought up to war strength on mobilization by absorbing the bulk of the most recently trained reservists. In most cases the first-line reserve divisions were slightly smaller than the active divisions, for instance with less artillery.

Older reservists formed the second-line reserve units: territorial or militia battalions and brigades for such duties as protecting lines of communication, guarding prisoners, garrisoning fortresses, and the like. Usually, these troops were armed with obsolescent weapons that had been replaced in the field army. In 1914, however, many such second-line units found themselves pressed into field service as combat troops.

The British Army, however, was different. As a small all-volunteer force its reserve, consisting of men who’d completed their service and returned to civilian life, was only sufficient to bring the home-based part of the Regular Army (six infantry divisions, one cavalry division and two cavalry brigades) up to war strength, and to replace initial losses. The Territorial Force, analogous to the US National Guard, was a part-time volunteer organization for home defense. Its members bore no obligation for foreign service though when war came, many Territorials did volunteer to serve abroad. In 1914 units of the Regular Army serving in the colonies were brought back to Britain, being replaced by Territorials.

The uniforms of the soldiers of 1914 present a varied picture. The British, the Russians and the Germans had already replaced the brightly colored uniforms of past times with khaki (for the first two) and gray-green (for the Germans) field uniforms. The Austro-Hungarian Army had done likewise, though its new blue-gray field uniform had been adopted with an eye to war on the mountainous frontier with Italy and proved rather too conspicuous for the Eastern Front. Only the French Army went to war in its traditional, highly visible colored uniforms—dark blue coats and madder-red trousers for the infantry of the line—not the least costly of the many mistakes it made in 1914. No army provided its soldiers with steel helmets.

The weapons in the hands of the soldiers of 1914 were few and basic by modern standards: the pistol, the rifle and bayonet, the machine gun and, for cavalry, the sword and lance. Machine guns were usually grouped in regimental machine gun companies (6-8 weapons), or battalion machine gun sections or platoons (2-4 weapons). Division artillery consisted mostly of light field guns with a caliber of 75mm to 80mm. Only the German and British divisions possessed significant numbers of modern light field howitzers capable of high-trajectory fire. German active infantry divisions had a battalion of eighteen 105mm howitzers and British infantry divisions had a battalion of eighteen 4.5-inch howitzers, both excellent weapons that quickly proved their worth.

Medium and heavy field artillery, such as it was, was controlled by the corps and armies, the German Army being somewhat better off than the others in this category of weaponry. Its twenty-five active corps each had a medium artillery battalion with sixteen 150mm medium field howitzers, and additional medium and heavy artillery units were attached to most of the field armies. In 1914 large numbers of heavy guns and howitzers permanently installed in fortresses were hurriedly dismounted and pressed into field service when the importance of heavy field artillery was realized.

Though such weapons were under development in the years leading up to 1914, no army possessed the submachine guns, light machine guns, mortars, grenade launchers, etc. that would be in widespread use by 1918. Even so, the firepower of an infantry battalion armed with magazine rifles and machine guns was many times greater than that of its 1815 ancestor. Supported by artillery, a 1914 infantry battalion in defensive positions was capable of stopping an attacking force many times its own size. Only the German Army, however, had troubled to equip its infantry with entrenching tools and train them in the construction of field fortifications.

But most professional soldiers had not grasped the implications of these revolutionary changes in military art and science—this despite the fact that the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) and the Balkan wars (1912-13) had plainly demonstrated the power of modern weapons. Mentally, they still lived in the nineteenth century, maintaining their faith in the tactical offensive, believing that a rapid, audacious attack could overcome any defense. Hence their continuing faith in cavalry. Hence their preference for light, rapid-fire field guns over high-trajectory howitzers and heavy artillery. Hence the emphasis, most notoriously in the French Army, on the importance of high morale, an aggressive spirit, and the bayonet. Small-unit tactics received scant attention, professional soldiers assuming that civilians in uniform would be incapable of executing complicated maneuvers under fire—though here again the British Army was exceptional, consisting as it did of well-trained, long-service regulars, many with considerable experience of colonial war.

Such were the armies that marched in August 1914—confident for the most part that the war would be over by Christmas.

Such were the armies that marched in August 1914—confident for the most part that the war would be over by Christmas.

Once the cannons start shooting ... there is no way to know where it will lead and when it will end.

Thank you for expanding on what I thought I vaguely recalled. Regarding your upcoming piece on advances in trench warfare, I would also be interested in hearing any comments you might offer on the latest iteration of trench warfare in the Ukraine-Russia War, inasmuch as aerial surveillance and precision targeting mean that slit trenches offer little protection against modern weaponry.