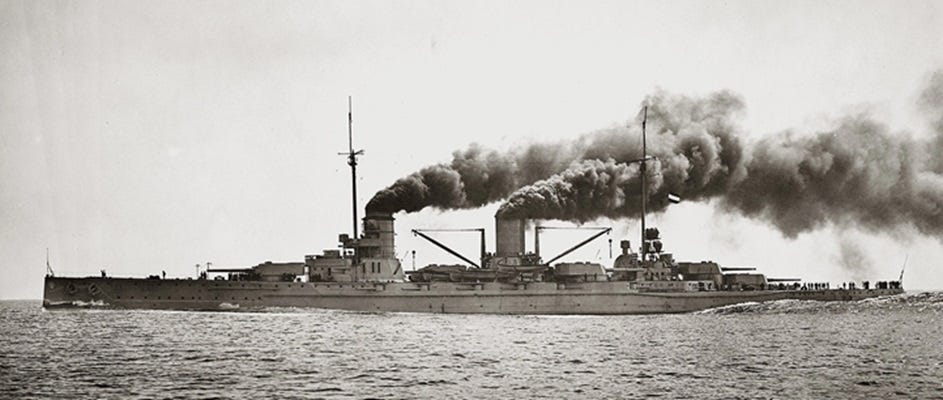

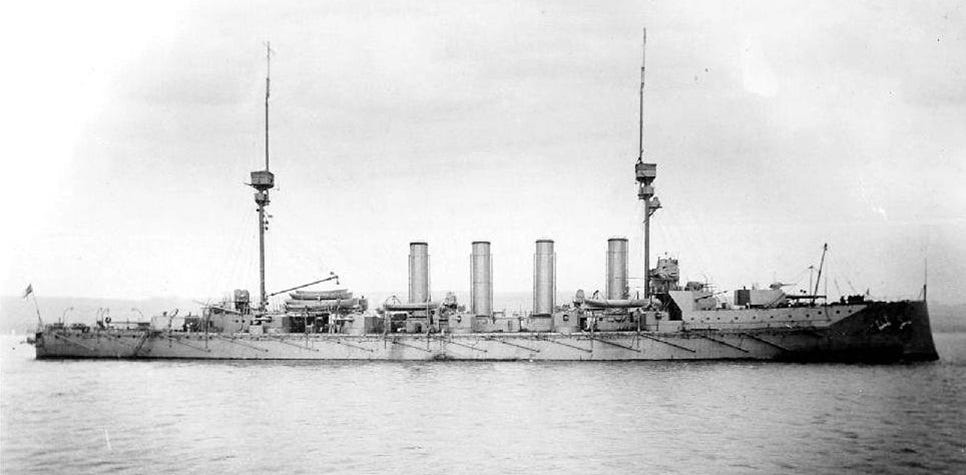

In 1914, though the main bodies of the British and German navies were concentrated in the North Sea theater, both maintained smaller squadrons around the world. In 1912 the Kaiserliche Marine had established the Mediterranean Division (Mittelmeerdivision), consisting of the battlecruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau. The former was a powerful modern unit, commissioned in 1912. With her main armament of ten 11in guns and top speed of 26 knots, she constituted a serious threat to the planned transfer of French troops from North Africa to the home country. The French Navy had nothing with which to counter Goeben. Its new dreadnought battleships were too slow to catch her, and it possessed no battlecruisers of its own.

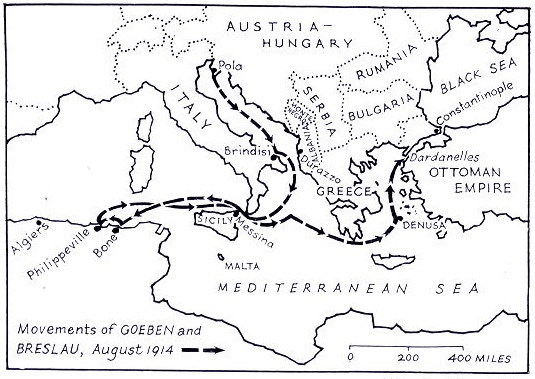

The Mittelmeerdivision had secret orders from the Kaiser governing its conduct in the event of war: either carry out attacks against French troop convoys in the western Mediterranean or break out into the Atlantic and make for Germany, at the commander’s discretion. In July 1914 with war imminent, the division commander, Rear-Admiral Wilhelm Anton Souchon, made for the Austro-Hungarian naval base, Pola, at the head of the Adriatic Sea, there to carry out repairs and refuel. The Mittelmeerdivision was back at sea on 3 August, bound for Algeria, when Souchon received word of the outbreak of war.

In accordance with the Kaiser’s orders, Goeben and Breslau made for Philippeville and Bone, the two ports on the Algerian coast at which French colonial troops were expected to embark for France. But early on 4 August, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (State Secretary of the Imperial Naval Office) and Admiral Hugo von Pohl (Chief of the Admiralty Staff) transmitted an order to Souchon, instructing him to sail to Constantinople—in direct violation of the Kaiser's prewar instructions and without his knowledge. They reasoned that a breakout into the Atlantic through the narrow Strait of Gibraltar, past the imposing British fortress of the same name, was impossible. And they believed, no doubt correctly, that if the Mittelmeerdivision remained in the western Mediterranean it would eventually be trapped and destroyed.

On the other hand, to run for Turkey appeared to open up some intriguing possibilities. The attitude of the Ottoman Empire, which had fallen under the rule of the reforming Young Turks in 1908, was favorable to the Central Powers. The Young Turk leader, Enver Pasha, was an admirer of Germany; in 1913 he had agreed to accept a military mission under Lieutenant-General Otto Liman von Sanders to assist in reforming the Ottoman Army along German lines.

Though the Ottoman government initially shrank from declaring war on France and Britain, the latter’s high-handed action in seizing two modern dreadnought battleships under construction in Britain for the Ottoman Navy caused widespread outrage in Turkey. The funds for the construction of the two ships had been raised by popular subscription, every Anatolian peasant household contributing its mite. Tirpitz and Pohl calculated that the appearance as if by magic of two fine, modern German warships at Constantinople would convince the Young Turks to throw in their lot with German and Austria-Hungary. Then, along with the Ottoman Navy, the Mittelmeerdivision could be committed to action against the Russians in the Black Sea.

But could Souchen get his ships to Constantinople? That was a doubtful question. Because of the Mediterranean Sea’s importance as a highway to Britain's Indian Empire, the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet was large and powerful: three battlecruisers, four armored cruisers, four light cruisers and sixteen destroyers. On 2 August the fleet was at Malta, and on that day its commander, Admiral Archibald Berkeley Milne, received fresh instructions from the Admiralty.

In the event of war, the Mediterranean Fleet was charged with three missions: covering the French troop convoys, keeping the Austro-Hungarian battle fleet bottled up in the Adriatic Sea, and dealing with any enemy ships at large in the Mediterranean. Milne was cautioned, however, to avoid engaging a superior force—an instruction that was to have unfortunate consequences. Another catch was that Britain was not yet at war with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Not until war was declared could the fleet take action against the Mittelmeerdivision and the Austrians.

Even so, on the face of things Souchen with his two ships was in a tight corner. The combined French and British fleets in the Mediterranean vastly outnumbered his small force. The three British battlecruisers alone, with their top speed of 25 knots and main armament of eight 12-inch guns apiece, could easily overwhelm his ships—if they could force him to accept battle. And that too was a doubtful question. In 1914, with naval aviation in its infancy, with no radar, with primitive radio communications, there was still a chance for a small force like Souchen’s, skillfully handled, to evade pursuit and reach safety. It would be a game of cat and mouse, with the Mediterranean Fleet’s superiority of numbers set against the Mittelmeerdivision’s speed and stealth.

When Souchen received his fresh instructions from Tirpitz and Pohl on 4 August, the Mittelmeerdivision was off the coast of Algeria and did not have sufficient fuel to sail immediately for Constantinople. He decided, therefore, to carry out the planned bombardment of the two Algerian ports before making for the Sicilian port of Messina, where coal could be obtained from the German merchant ships gathered there. The Mittelmeerdivision conducted its bombardment, then turned east. Three French squadrons of battleships and armored cruisers were in the area, but the French commander had expected the Germans to attempt a breakout to the west, so Souchen was able to slip away.

At 9:30 in the morning on 4 August the Mittelmeerdivision was sighted by two British battlecruisers, Indomitable and Indefatigable. No engagement ensued, however, for Germany and Britain were not yet at war. The British battlecruisers began shadowing the German ships but soon lost contact. Though their design speeds were nearly identical, both the British and German ships were suffering from various mechanical problems and as things worked out the latter enjoyed a slight speed advantage.

Admiral Milne had reported the Mittelmeerdivision’s position to the Admiralty, but not its course. Winston Churchill (the First Lord of the Admiralty) and Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg (the First Sea Lord) therefore assumed that Souchen still intended to attack the French troop convoys. They authorized Milne to engage the Germans if this happened, declaration of war or no, a decision that was promptly vetoed by the full British cabinet. There would be no hostilities between British and German forces until war was declared—which happened late in the evening of 4 August, after confirmation of Germany’s violation of Belgian neutrality.

Early in the morning on 5 August, Goeben and Breslau entered the port of Messina. Italy had declared its neutrality and the Italian authorities insisted that Souchen must leave within twenty-four hours. Transferring coal from the German merchant ships was a difficult business and his ships were unable to take on sufficient fuel to reach Constantinople before the deadline expired. Moreover, fresh instructions arrived from Tirpitz in Germany, informing him that in view of the Ottoman Empire’s continuing neutrality he should not make for Constantinople.

The only alternative was Pola, where the Mittelmeerdivision would probably remain bottled up for the rest of the war. This being unpalatable to him, Souchen decided to disregard his orders and go to Constantinople anyway. He hoped that his arrival at the entrance to the Strait of the Dardanelles would force the Ottoman’s government’s hand and bring Turkey into the war on the side of the Central Powers. But if not, he was determined to pass the Strait by force if necessary, bringing Constantinople under his guns. Few decisions made during the Great War by any commander would prove as consequential.

But it occurred to neither Admiral Milne nor to his superiors in London that the German ships might make for Constantinople. His instructions from the Admiralty were to maintain surveillance of the Adriatic in case the Austrian battle fleet attempted a sortie, and to be on the alert for an attempt by Souchen to attack the French convoys or seek refuge at Pola. Milne therefore positioned his 1st Cruiser Squadron (four armored cruisers and eight destroyers under Rear-Admiral Ernest Troubridge) at the entrance to the Adriatic Sea, while he with the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron patrolled northwest of Sicily. Only one British ship, the light cruiser Gloucester, was detailed to cover the southern exit of the Strait of Messina, between Sicily and the toe of the Italian boot.

Souchen put to sea on the evening of 6 August, while it was still light, and turned north. This was a ruse; the German admiral planned to shake off his pursuers by reversing course after dark and passing through Strait of Messina. His immediate objective was to rendezvous with a German collier off the coast of Greece. Gloucester spotted the German ships, reported their location and course to Milne, and began to shadow them. The British cruiser attempted to slow down the Mittelmeerdivision by engaging Breslau, but the exchange of fire was inconclusive, and Milne ordered Gloucester to break off the pursuit at Cape Matapan. He also ordered Troubridge with his armored cruisers and destroyers to intercept the Germans.

Even after receiving Gloucester’s report the British commander expected the Germans either to turn west or head for Pola. If the former, he would be waiting with his battlecruisers; if the latter, Troubridge’s squadron could deal with them. He was in no hurry, therefore, to head east, not doing so until just after midnight on 8 August. An erroneous signal from the Admiralty that Britain and Austria were now at war further confused the situation. The next day, however, Milne was finally given positive instructions to "chase Goeben which had passed Cape Matapan on the 7th steering north-east."

Because the British battlecruisers were still far to the west, this order from the Admiralty could only be executed by Troubridge. Milne, however, seems not to have considered that the Goeben was superior to the British armored cruisers. The German ship was faster than they were, and her 11in guns outranged their 9.2in main batteries. Souchen, therefore, could engage Troubridge’s ships from outside the maxim range of their guns.

Troubridge judged that his only chance for a successful outcome would be to intercept the Mittelmeerdivision at dawn in favorable conditions of light, with the German ships to the east of his squadron. While his cruisers occupied the Germans’ attention, his destroyers might be able to deliver an attack with torpedoes. But when a dawn interception proved to be impossible, Troubridge signaled Milne that he would not attempt to bring the enemy to battle. He later cited the Admiralty’s instructions to avoid engaging a superior force as his reason for abandoning the chase.

So Souchen was free to proceed to Constantinople. He refueled from his collier on 9 August and by midmorning of the next day Goeben and Breslau were standing off the entrance to the Dardanelles. Permission to proceed was soon received and the Mittelmeerdivision made its way to the Turkish capital. Its arrival there was a fateful event, heralding the Ottoman Empire’s entry into the war on the side of Germany and Austria.

In Britain, the failure to destroy Goeben and Breslau caused an uproar. Admiral Milne was removed from his command and never received another one—this though the Admiralty always alleged that Milne was not to blame for the debacle. Rear-Admiral Troubridge was court-martialed in November 1914, the charge being that “he did forbear to chase His Imperial German Majesty's ship Goeben, being an enemy then flying.” Thanks to the Admiralty’s caution against engaging a “superior force,” he was “fully and honourably acquitted.” But though Troubridge served on active duty until the end of the war, he never received another command at sea.

The unsuccessful pursuit of the Geoben showed that the Royal Navy suffered from serious deficiencies of command and leadership. The Admiralty’s instructions to the Mediterranean Fleet were often vague, misleading or incorrect, the failure to foresee that Souchen might make for Constantinople was a serious lapse, while the commanders on the spot exhibited both lack of initiative and poor judgement. And even worse news was to come from the Pacific, where the pursuit of another German squadron ended catastrophically for the RN off the coast of Chile.

Troubridge was treated gently as Admiral Byng could attest.