INTRODUCTORY NOTE

This article is the first in a projected series on the naval dimension of World War II. The war at sea, 1939-45, has always been a subject of absorbing interest to me. To understand its prehistory and its course is to deepen one’s understanding of the war as a whole. Therefore, I humbly dedicate this article and those to come to the officers and bluejackets of the United States Navy, 1941-45, and to the officers and sailors of the Allied navies, Britain’s Royal Navy in particular, who played so prominent a role in the salvation of the world.

NOTE ON NOMENCLATURE

The following abbreviations are used in this article: AA (antiaircraft gun), AS (antisubmarine) DC (depth charge), DCT (depth charge thrower) DP (dual purpose surface/antiaircraft gun), TT (torpedo tubes), HMS (His Majesty's Ship), USS (United States Ship). RN (Royal Navy), USN (United States Navy). Relevant USN hull type codes were DE (destroyer escort), ADP (fast transport) and DER (destroyer escort radar picket). In US Navy parlance, guns of 3in caliber and larger were described by caliber and barrel length as a multiple of caliber. Thus the 3in/50 DP gun had a caliber of three inches and a barrel length of 150 inches.

Few people today appreciate the size and scope of the United States’ 1941-45 industrial mobilization. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt dubbed America the “arsenal of democracy” even before the country entered World War II, and so it was. Guns, tanks, vehicles of all kinds, warplanes, munitions and countless other items were produced in quantities that boggle the mind. It was the greatest wartime industrial effort put forth by any nation—ever.

Particularly noteworthy were the achievements of the shipbuilding industry. In many ways the United States Navy was the most impressive of the Allied fighting services, and one reason for this was the quality and quantity of the ships themselves. Twenty-five fleet aircraft carriers (“Essex” class) and eleven light fleet aircraft carriers (“Independence” and “Saipan” classes) headed the wartime construction list—representing the tip of an enormous iceberg. There were also four “Iowa”-class battleships, numerous cruisers and fleet destroyers, and countless smaller warships, among them the astonishing total of 507 destroyer escorts (DE)—the latter all constructed between 1942 and 1945. An additional 50 DEs were completed as fast transports (ADP; see below).

The DE program originated with a British request. Early in the war the Royal Navy had identified a requirement for a warship intermediate in size and capability between small escorts such as corvettes and frigates, and fleet destroyers. The result was the Hunt class, built in four series. These ships had the same general layout as a full-size destroyer, but were smaller, with less firepower. The “Hunts” proved highly effective in their designed role as antisubmarine/antiaircraft escorts and the RN wanted many more of them. But since the British shipbuilding industry was already stretched to the limit, only the United States could provide such ships.

In fact the destroyer escort concept had been considered and rejected by the US Navy, prewar studies concluding that full-sized fleet destroyers, already in full production, could better meet the USN’s escort requirements. But in June 1941 the British Supply Council in North America asked if destroyer escorts could be provided for the RN out of US resources; a long-term program of 100 units was suggested. A 50-ship program received presidential approval in August, and the type was designated British Destroyer Escort (BDE). From these modest beginnings evolved the vast DE construction program.

The 1942-45 DEs were divided into six classes, but these were really variations of the same basic design, exemplified by the characteristics of the initial “Evarts” class—also known as the GMT class—of which 97 were constructed. These ships had a standard displacement of 1,192 tons, were 283 feet long with a beam of 35 feet, and were powered by two General Motors diesel engines (hence the GMT or General Motors Tandem designation) giving a top speed of 20-22 knots. This was some 15 knots slower than a fleet destroyer but adequate for escort work. Average convoy speeds were 12-14 knots and most German U-boats could make no more than 18 knots surfaced and eight knots submerged.

The GMTs were were armed with three 3in/50 dual-purpose guns, one quadruple 1.1in (28mm) antiaircraft gun, nine single 20mm AA guns, one Hedgehog AS mortar, eight DCT and two DC racks. Ship’s complement was 156 officers and men. Later on the light AA armament was changed to one twin 40mm Bofors and eight 20mm AA—roughly standard for all DE classes by 1944. The "Evert" class and later DEs were fitted with the latest search and attack sonar equipment. It was housed in a retractable pod that when deployed reduced the DE's sea speed to 10-12 knots.

All but three of the GMTs were completed by the end of 1943. Of the class, 65 were commissioned in the US Navy and 32 went to the Royal Navy as the “Captain” class. The RN transfers were not fitted with the quadruple 1.1in AA gun mount, receiving extra 20mm guns instead.

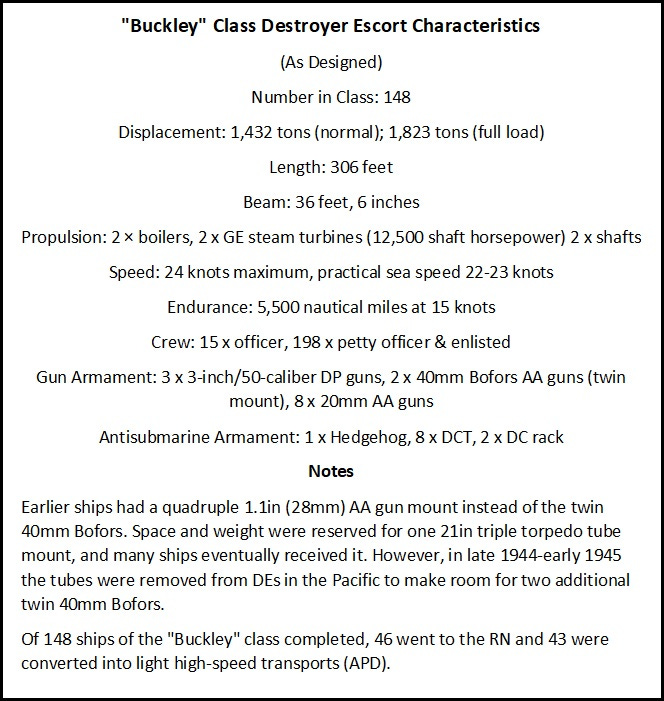

Next came the “Buckley” class, also known as the TE class, reflecting a change from diesel engines to steam-fired General Electric turbo-electric propulsion. They were also longer (300 feet) than the GMTs. Together, the TE power plant and the extra length gave the Buckley class a better turn of speed than their predecessors: 23-24 knots. Initially the TEs carried the same armament as the GMTs, but many of them later received two 5in/38 DP guns in place of the 3in/50s—the original DE design having incorporated space and weight reservations to accommodate this heavier armament. Space and weight had also been reserved for a triple torpedo tube mount, and many of the TEs eventually received it. With 148 units constructed, the TEs constituted the largest wartime DE class; 46 went to the Royal Navy. The only other foreign transfers during the war were fourteen of the subsequent “Cannon” (DET) class, of which six went to the Free French Navy and eight to the Brazilian Navy.

The following four DE classes were similar to the TEs, differing mainly in the type of power plant. Many of the later ships were completed with 5in/38 guns and torpedo tubes, though in 1944-45 the tubes were removed from DEs in the Pacific to make space for extra 40mm AA guns. At one point in 1943 there were no fewer than 1,005 DEs on order—this to ensure that a minimum of 300 would be delivered by the end of the year. But 305 were canceled in late 1943, 135 in 1944 and two after the war in 1946.

The DEs were designed for prefabricated construction. Components were manufactured all over the United States for delivery to shipyards were final assembly took place. Though it took six months to construct the first DEs, later on they were being turned out in six to eight weeks. By way of comparison, construction of the USS Gearing, name ship of the USN’s final wartime fleet destroyer class, took ten months from laying down to commissioning.

In the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and the Pacific, the DEs with their modern sonar and heavy antisubmarine armament were successfully employed as convoy and amphibious force escorts. Particularly notable was their service in the latter theater. For the campaign being waged against Japan, the US Navy evolved the task force concept: in land warfare parlance, a combined arms organization. Task forces embodying the most modern ships—variously aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, fleet destroyers—provided distant cover for landing operations by acting on the offensive against enemy naval forces. The actual landings were conducted by task forces including attack transports, cargo ships, specialized amphibious warfare vessels, etc., with direct gunfire and air support provided by older battleships, cruisers and the small escort aircraft carriers. DEs were the primary escorts for such task forces.

At the Battle off Samar (25 October 1944) the three “Fletcher”-class fleet destroyers and four DEs of Task Unit 77.4.3 (call sign Taffy 3), an escort carrier group, fought a valiant action against a greatly superior Japanese force that was attempting to close with and destroy the Leyte invasion force. Attacking with guns and torpedoes, the “little boys” of Taffy 3 staved off disaster by preventing the Japanese from reaching the highly vulnerable US invasion fleet. Among the US ships lost was USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413) of the “John C. Butler” class, sunk in action against a Japanese heavy cruiser three times her size—which she severely damaged with gunfire and torpedoes at point-blank range before being sunk herself.

During the war, no fewer than 94 DEs were modified to serve as high-speed light transports (APD), reinforcing the prewar flush-deck APD conversions in the Pacific theater. Of the “Buckley” class, 43 were modified after completion as DEs; of the “Rudderow” class 50 were modified while under construction and one after completion as a DE. The conversion included an enlarged superstructure to accommodate troops, with davits added to handle four small landing craft (LCVP). Gun armament was altered to one 5in/38 forward plus three twin 40mm Bofors and six single 20mm AA. The APDs carried no Hedgehog but they did retain DC racks and throwers.

Like their flush-deck predecessors, the DE APD conversions proved extremely useful in the Pacific and saw arduous service: transporting raiding parties and underwater demolition teams, running supplies, escorting convoys and conducting antisubmarine patrols. A few DEs of the “Buckley” class were modified to serve as radar pickets (DER), armament being reduced to make room for long-range radar equipment. Though not very successful, this modification foreshadowed the more extensive DER conversions of the Cold War era.

The DEs transferred to Britain as the “Captain” class received only minor modifications in RN service. Most served in the Atlantic as antisubmarine escorts, but some were allocated to Coastal Forces as flotilla flagships. These ships were fitted with additional light weapons, most prominently a 2-pounder (40mm) pom-pom in the bow against German E-boats. Three other “Captains” were modified to serve as amphibious command ships for the Normandy invasion. They lost all their antisubmarine armament and the aft 3in/50 gun, and had deckhouses added to accommodate command staff and additional communications equipment. At the end of the war, all of the “Captains” were returned to the US.

After 1945 almost all of the DEs were quickly decommissioned. Most of the “Everts” class were struck from the Navy List and scrapped in 1946-47. The ships of the “Buckley” class went into the Reserve Fleet, where they remained until being stricken and scrapped from the mid-Sixties to the mid-Seventies. Of the “Canon” class, large numbers were transferred to friendly foreign navies, e.g. six to the Royal Netherlands Navy in 1951-52 as the “Van Amstel” class. Other DEs were transferred on loan to the US Coast Guard (1951-54), and many were recommissioned for service during the Korean War. They also proved useful as training ships for the Naval Reserve and at least a dozen were so employed. Finally, a number of DEs were reconstructed to serve as radar picket ships (DER) in support of carrier task forces. Thirty DEs were so converted and the last of them did not leave active service until the mid-1970s.

The very last DE in service was the Philippine Navy’s BRP Rajah Humabon (PS-11), the former USS Atherton (DE-169) of the “Canon” class. After service in World War II she was decommissioned and placed in the Reserve Fleet until 1955, when she was transferred on loan to the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force along with a sister ship. As Hatsuhi (DE-263) she served for twenty years, being returned to the US in 1975. In 1978 she was refitted and transferred to the Philippine Navy, with which she was destined to serve for forty years. At the time of her final decommissioning in 2018, Rajah Humabon was classified as a patrol ship, with all antisubmarine weapons removed. Otherwise, however, the old veteran looked much the same as she had during her wartime service with the US Navy.

A couple random points.

The Roosevelt administration anticipated the US involvement in WW2, so the US ship building effort really started in 1940.

(Contrast that foresight with our current lethargy as the possibility of war with China increases.)

Then, as now, the US ship building industry lacked both enough skilled workers and enough ship yards.

We got around the problem by modifying building techniques and training people to produce. And by building green field shipyards.

Today that same lack of workers and shipyards is considered an insurmountable problem.

An additional point.

Back then, naval architects designed world class ships - quickly.

Contrast that to the interminable design process for the new frigates and icebreakers.

Time for our naval policy makers to derive some inspiration from the past.

Fantastic!