The Great War: Recommended Reading

B.H. Liddell Hart's classic one-volume history of the conflict

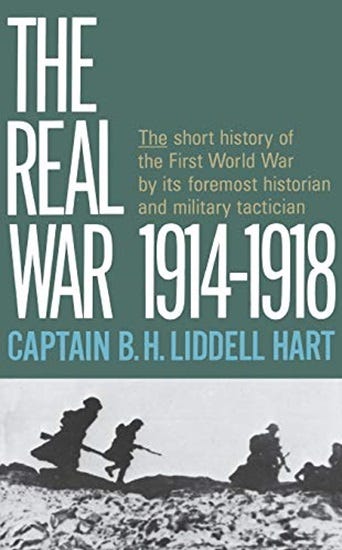

Ever since the guns fell silent on 11 November 1918, countless military histories of the Great War have been written and published. Official histories were compiled by the general staffs of the belligerents, scholarly works appeared, popular accounts and personal memoirs caught the imagination of the public. No one could possibly read them all, of course, and of those I’ve read myself—a goodly number—there are a select few that I’d recommend to a general audience. The Real War by Captain B.H. Liddell Hart is foremost among them: a classic first published in 1930 that has remained in print ever since.

Basil Henry Liddell Hart was born in Paris in 1895. His father was a Methodist minister whose family came from Gloucestershire and Herefordshire in England. His mother’s family, the Liddells, were Scottish. He was educated at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge and when war broke out in August 1914, Liddell Hart volunteered for the British Army, accepting a commission as a second lieutenant in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry.

Sent to France in 1915, Liddell Hart served briefly at the front before suffering a severe concussion during an artillery bombardment that sent him back to England to convalesce. Returning to the front as a captain in 1916, he fought in the Battle of the Somme, where his battalion was practically wiped out. Liddell Hart himself was wounded three times, not too seriously, but was sent home again after being badly gassed. He never returned to France, spending the rest of the war as a training officer. Liddell Hart remained in uniform after the war, but two heart attacks, probably due to gas poisoning, compelled him to retire in 1927. Thereafter he became one of Britian’s most prominent military commentators, and a trenchant critic of British wartime strategy and command.

Liddell Hart’s wartime experiences made a profound and lasting impression on him. He came to believe that Britian’s commitment of a large army to the Western Front had been a fundamental—and costly—strategic error. Historically, he noted, British wartime strategy left continental warfare to allies, supporting them with subsidies and a small expeditionary corps, while using the mobility afforded by naval power to strike the enemy’s vulnerable areas away from the main front: a policy of “limited liability.” This is the concept that informs his analysis of the Great War.

The Real War, therefore, is part history and part polemic—a point that readers should bear in mind. That being said, the book provides a coherent chronological account of the war. After two introductory chapters on the origins of the conflict and the opposing forces and plans, the military course of events is presented in five sections. Each section begins with an introduction to the relevant phase of the war, followed by more detailed accounts of its major events. Perhaps recalling Clausewitz’s famous analogy of wrestling to war, Liddell Hart gives them titles borrowed from wrestling. “The Clinch,” for example, deals with the first battles, east and west, that set up the pattern of the war. And despite a certain emphasis on the famous Western Front battles, other theaters of war—the Eastern Front, Italy, Rumania, Turkey, Palestine, Mesopotamia, the war at sea— are not neglected.

Throughout The Real War, the themes of limited liability and the indirect approach recur, most clearly in the author’s very critical account of the Dardennes campaign. This unsuccessful attempt to knock out the Ottoman Empire by leveraging Allied naval superiority is indeed a sad tale of muddle and indecision. Had the operation succeeded, the route north into the Black Sea would have been opened, enabling British and French aid to reach their hard-pressed Russian ally. But whether this alone would have sufficed to bring down Germany and Austria-Hungary is a doubtful question—though Liddell Hart makes the best possible case that it might have done so.

Regarding the Western Front, The Real War is sharply critical of the lack of imagination exhibited by the British and French commands from start to finish. The author points out that though the Allied offensives were often well conceived from the strategic point of view, they took insufficient note of the tactical realities.

Until 1917, the opinion of British and French headquarters was that with enough artillery and sufficient troops, one final push would bring the German Army to its breaking point. And curiously enough, there was some truth in this. The Battle of the Somme, remembered as a disaster for the British Army, had been almost as disastrous for the Germans in terms of casualties. There was this difference, however: The German command responded to that crisis by abandoning the Somme line, shortening the front by some twenty-five miles. And the new front, called the Hindenburg Line by the Allies, replaced linear trench defenses with a new system of defense in depth. Liddell Hart notes with approval “that [the German command] had the moral courage to give up territory if circumstances advised it”—the clear implication being that the Allies were not so wise.

Liddell Hart became closely identified with the “tank prophets” of the interwar British Army, as previewed by his treatment of “The Growing Pains of the Tank” in The Real War. Once again he is critical of the British command, which not only failed to appreciate the tank’s potential as a means of breaking the trench warfare deadlock but waged a bureaucratic war against the civilian officials and soldiers who were promoting the new weapon. In this, happily, the naysayers were unsuccessful, and the tank survived to play a major role in the defeat of Germany.

In The Real War’s “Epilogue,” the author pronounces his verdict on the outcome of the conflict, which is that Britain’s Royal Navy won it. Its weapon was blockade, which slowly but surely sapped German strength and will: Liddell Hart’s “indirect approach” applied at the highest level of strategy. He argues that Germany’s last great bid for victory by offensive action in the spring of 1918 was motivated by a consciousness among Germany’s civilian and military leadership that the country could no longer stand on the defensive, with hopelessness, hunger and revolution stalking the land—adding, however, that if Germany had opted for a defensive policy, the Allies might have settled for a negotiated peace on more favorable terms for their adversary.

As an introduction to the history of the Great War, The Real War holds its own against later works. Clearly and concisely, it describes the origins and course of the conflict, with due regard for its global character. And though Liddell Hart has a definite point of view, opinion and fact are fairly balanced. His account of the war is readable, provocative and highly recommended.

Liddell Hart's work is also highly respected on the continent, where military officers and historians always treated it with great regard.