Part Nine: Opening Round in the East (4)

(For clarity, German units are rendered in italics.)

Legends cluster around the famous Battle of Tannenberg. It was claimed, for instance, that in the years before the war General von Hindenburg had studied the problem of defending East Prussia and developed the plan that produced victory in August 1914. But this was no more than patriotic mythmaking, put out to bolster Hindenburg’s reputation. In fact, the Germans had their course of action laid out for them by the military geography of East Prussia and the configuration of its rail net. By the time that Hindenburg and Ludendorff arrived at the Eighth Army’s headquarters its staff officers, a certain Colonel Max von Hoffman prominent among them, had the plan ready: Rennenkampf’s First Army in the north would be held off by a thin screen of cavalry and Landwehr brigades while the bulk of the German forces hurried south to confront Samsonov’s Second Army.

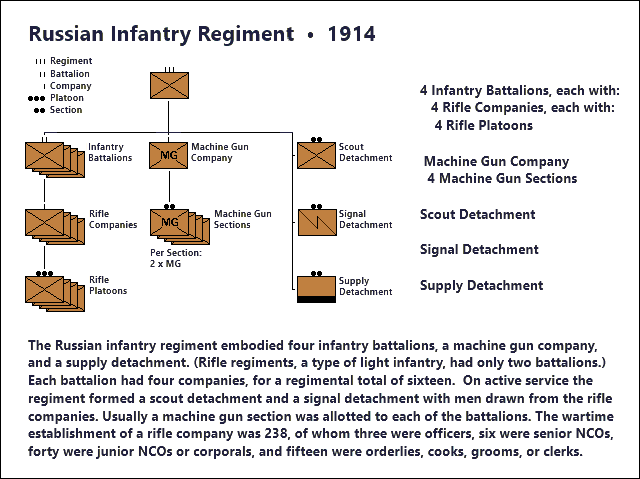

Meanwhile, on the other side of the hill, the actions of the two invading armies were becoming more and more disjointed. Their higher headquarters, Northwest Front, was far in the rear at Volkovysk and its commander, Zhilinskiy, provided nothing by way of direction beyond exhortations to speed up the advance. Despite having won a tactical victory at Gumbinnen, Rennenkampf was convinced that he faced most of Eighth Army and could not resume the offensive until his supply service sorted itself out. Samsonov, however, was more receptive to Zhilinskiy’s prodding. His troops had met the German XX Corps on 22 August and pushed it back in several places. This encouraged Samsonov to press on despite his own supply problems.

Zhilinskiy’s contribution was to bombard Rennenkampf with demands to get First Army moving in support of Second Army’s attack. But Rennenkampf was not short of excuses for doing nothing: German opposition, his own army’s exhaustion, lack of food, fodder and ammunition.

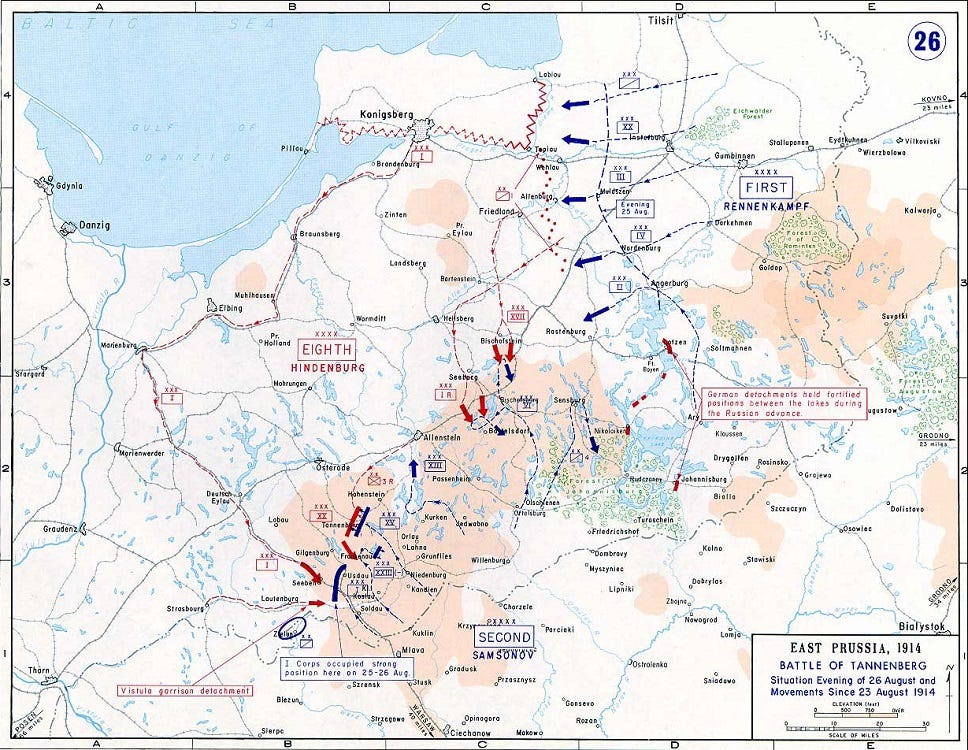

As Zhilinskiy nagged, Rennenkampf sat still and Samsonov marched into East Prussia, Eighth Army's redeployment proceeded. By 25 August I Corps had been moved from the Königsberg area to a strong defensive position facing Second Army’s left flank, while I Reserve Corps and XVII Corps had been moved to positions facing Second Army’s right flank. These redeployments had been conducted smoothly and rapidly: a tribute to the efficiency of the Eighth Army staff.

Of these developments, Samsonov had no inkling. He thought that his army faced XX Corps only, and that the prospect of a great victory beckoned. His plan was for Second Army’s center in the strength of three corps to attack XX Corps, nailing it in place. Meanwhile Second Army's left and right flank corps would advance to envelop the enemy and complete his destruction.

But in reality, Samsonov was leading his army into a trap. On 26 August, after an intemperate argument with Ludendorff over his supply situation, General von François launched I Corps into an attack on the Russian right flank. His corps artillery had not all arrived, however, and François did not press the attack too strongly that day. On the front of XX Corps there was heavier fighting, one Russian infantry division being routed and broken up. But Second Army was still gaining ground and at Eighth Army headquarters nerves began to fray. A report that First Army's advance was picking up speed moved Ludendorff to suggest that the battle should be broken off. But Hindenburg steadied his Chief of Staff, and the report was soon found to be exaggerated.

Also on 26 August Eighth Army was notified by OHL that three corps and a cavalry division from the western armies were being dispatched to East Prussia. Still confident of victory in the West but concerned about the situation in the East, Moltke thought that he could spare the troops. Ludendorff replied that the battle would probably be decided before the reinforcements could arrive; however, he added, they’d certainly be welcome.

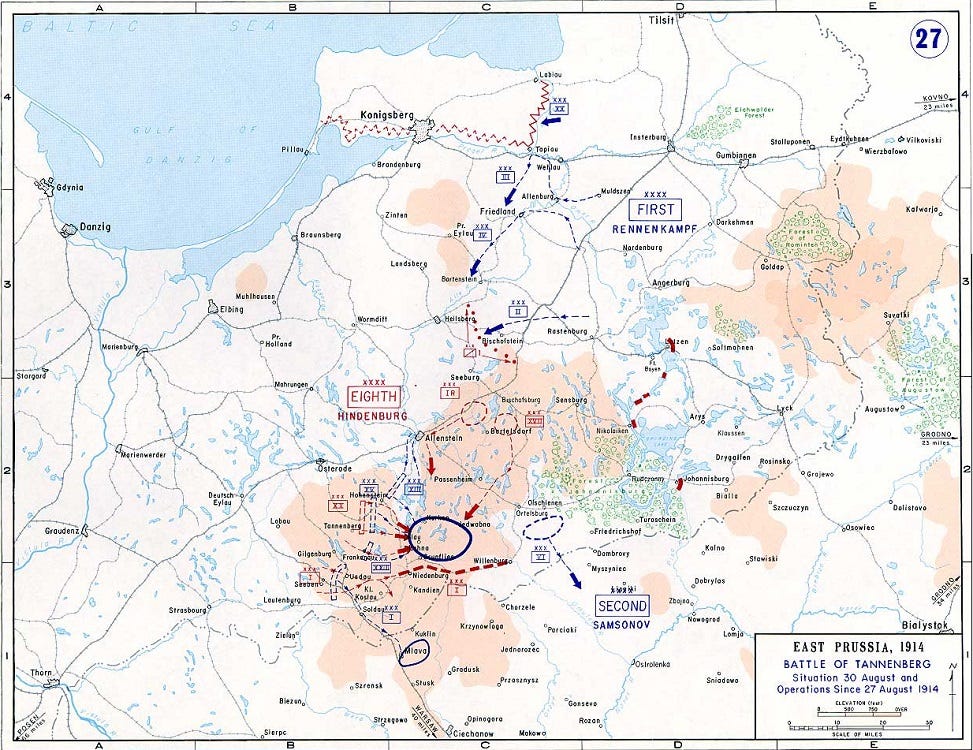

But there was no real reason for Moltke’s concern. On 27 August, with his artillery concentrated and his troops resupplied, François launched a full-scale attack that drove the Russian left flank (I Corps) back in confusion. The same thing happened on the Russian right, where XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps, now fully concentrated, attacked and drove back VI Corps on 27-28 August. That left Samsonov’s center group—three corps strong—in a perilous position, with German forces advancing past both its flanks. This, ironically, was the fate that the Russian commander had planned for XX Corps. By the time Samsonov realized what was actually happening, it was too late. Troops of I Corps and XVII Corps made contact on the evening of 28 August, encircling the three center corps of Second Army.

Though Samsonov ordered a retreat, the German cordon prevented all but isolated groups from slipping away. Throughout the day on 29 August the Russians launched desperate attacks in an effort to break out, thousands dying in the attempt. By 30 August the surrounded troops had lost all cohesion and mass surrenders began. But General Samsonov was not among the prisoners. He chose instead to commit suicide, lamenting to his staff: “The Tsar trusted me. How can I face him after this disaster?”

In all, Second Army lost 78,000 killed or wounded and 92,000 made prisoner. Three corps were annihilated and two more were chased out of East Prussia in disorder. At the end of August, the remains of Second Army amounted to less than the strength of a division: perhaps 12,000 troops in all. As for First Army, it had indeed resumed its advance on 26 August, though moving at a snail's pace. The aggressive behavior of the German screening force—cavalry supplemented by Landwehr troops drawn from the garrison of Königsberg—continued to deceive Rennenkampf that he was facing much stronger opposition. On the day of crisis, 28 August, his leading troops were still fifty miles distant from Second Army’s right flank.

Having disposed of Second Army, the Germans redeployed back to the north. A week after Tannenberg, in the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes, First Army was driven out of East Prussia. With the lesson of Samsonov’s catastrophe before his eyes, Rennenkampf made sure to retreat in good time and his army, though badly battered, regained Russian soil in one piece.

Though Tannenberg was a great victory that gave a tremendous boost to German morale, it was far from decisive. Even as Samsonov’s army was being destroyed, fresh Russian forces were reaching the front in ever-greater numbers. In Galicia, the Austro-Hungarian Army had met disaster. And far away in France, the German offensive was beginning to falter. Germany had gained a breathing space, but it was clear that the war would continue for a long time.

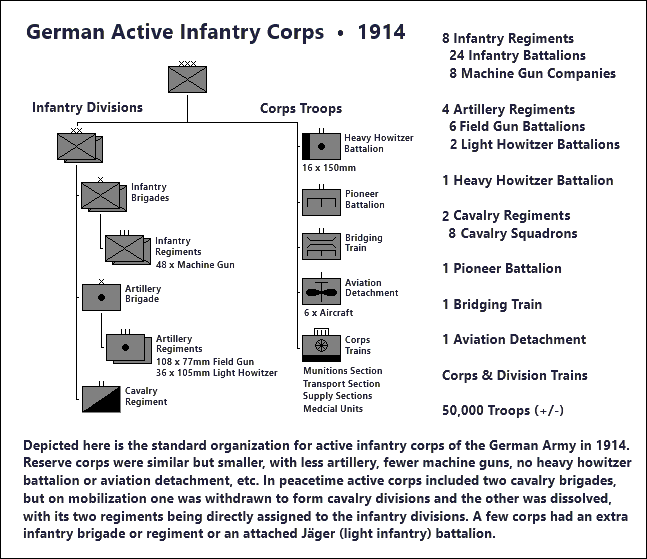

Tannenberg did show that the German Army was a military instrument of considerable efficiency. As has been noted, the correct line of operations in East Prussia was obvious from a glance at the map. It was the execution of that operation that demonstrated German superiority: the handling of reserves, the quality of the staff work, the management of the rail net. The Russian Army did not lack for brave soldiers. It had some—if no surplus—of capable commanders. In 1914 it was reasonably well armed and equipped. But there was nothing on the Russian side to compare to the German Army’s Großgeneralstab (Great General Staff) or even to its NCO corps, whose excellence explains why even second-line Landwehr formations fought so effectively. That the Germans did not hesitate to strip fortified areas of their garrisons and send such relatively elderly reservists into the field demonstrated a level of confidence in NCO leadership that other armies did not share.

After Tannenberg rumor suggested that the mutual animosity of Rennenkampf and Samsonov deterred the former from hurrying to the latter’s relief. Supposedly the two had argued violently during the Russo-Japanese War and actually came to blows on a railroad station platform in Manchuria. While the personal factor should never be discounted—think of Hitler’s deep dislike of the officers who dominated the German General Staff—there probably was nothing much to such stories. Rennenkampf’s caution was natural enough in the circumstances, and no action was taken against him at the time. His dismissal from the Army in October 1915 was due to his ethnic background. Rennenkampf was a Baltic German, born in Estonia, and with the war going badly for Russia such men made for convenient scapegoats. He was even tried for treason but was acquitted and permitted to retire with full pension rights. But in 1918 he was arrested by the Bolsheviks and after refusing a demand to take service with the Red Army, Rennenkampf was shot.

On the German side, Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff were hailed as the saviors of East Prussia and the prestige they gained thereby was destined to elevate them to the summit of power. But the famous partnership was not as smooth as legend had it. Hindenburg was quite well aware that his Chief of Staff regarded himself as the real brains of the operation and he, Hindenburg, as a mere figurehead. For his part Ludendorff resented the share of credit that went to Hindenburg for victories that he, Ludendorff, believed were due to his own genius. But despite these frictions, the two men formed an effective team. Stolid, phlegmatic, unimaginative but decisive, Hindenburg (usually) provided the steadying hand that Ludendorff, intelligent, driven, highly professional but nervy and high-strung, so greatly needed.

As for Colonel Max von Hoffman, who was deputy chief of operations at Eighth Army headquarters during Tannenberg, it is to his diary that we owe much of our knowledge of what went on in the German headquarters during those days of crisis. An extremely intelligent man with a sardonic streak, he was known to have remarked that the famous Duo had received the plan of battle ready made on the day of their arrival in East Prussia—a claim, indeed, with a good deal of truth in it. Hoffman remained on the Eastern Front throughout the war, playing a notable role in later battles and campaigns.

Von Hoffmann is one of those figures who seems to have added far more value to campaigns than his rank or rewards would suggest.

His name shows up in many major campaigns.

Don't know much about him.