Part Fifteen: Conclusion of the Opening Round

With the end of the Battle of Flanders and the onset of winter, fighting on the Western Front died down. Both sides were exhausted and frustrated by the failure of their initial plans. But General Joffre, the French commander-in-chief, remained steadfast in his determination to resume the offensive at the earliest possible moment. Ever the optimist, he was undaunted by the horrific casualties suffered by the French armies in the Battle of the Frontiers. The Germans too, he argued, had suffered heavily and were vulnerable to attack in the great bulging salient between Arras and Rheims. The British, whose army in France was slowly expanding, were of similar mind.

On the Allied side there was no doubt among the military commanders that it was both necessary and possible to win the war by defeating the Germans in France and Flanders. But as events were to show, this optimistic attitude was based on an overestimation of German losses and an underestimation of the strength of the defense in trench warfare. The French and British generals were adamant in their belief that the Western Front was the theater of decision. Only a few skeptics such as Winston Churchill ventured to suggest that strategic opportunities might be found elsewhere.

On the German side, disagreements had already arisen between General von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the OHL, and the heroes of the Battle of Tannenberg. Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff—the Duo as they came to be called—argued that the vulnerability of Russia, so plainly evident in the opening round, presented Germany with a golden opportunity. If Russia could be knocked out of the war, the German Army would then be free to concentrate against the Allies on the Western Front, thus guaranteeing victory.

Falkenhayn disagreed. He doubted that it was possible decisively to defeat Russia, a huge country, rich in manpower, whose vast spaces would swallow up the German and Austrian armies. Despite the unsatisfactory outcome of the opening campaign in the west Falkenhayn remained convinced that France and Flanders constituted the decisive theater of war. Thus originated the long, acrimonious strategic debate between Germany’s “westerners” and “easterners.” It was a debate complicated by the shaky condition of the Austrian armies, which had been soundly trounced in the war’s opening round. Thanks to that and much against his inclination, Falkenhayn was compelled to dispatch reinforcements to bolster up the Austrian sector of the Eastern Front. Whatever Austria-Hungary’s military deficiencies, Germany could ill afford to write off its major ally as excess baggage.

Another complication was Falkenhayn’s conviction that further offensives in the west would be futile. The Germans’ failure to break through at Ypres in October-November 1914—though they came close to doing so—and the high casualties they sustained had shaken his faith in victory by decisive battle. He now argued—and here the Chief of the OHL was prescient—that the war would last a long time, that it would be a war of material, and that attrition would determine the outcome. In effect, he reverted to the strategy of Ermattungsstrategie, exhaustion of the enemy.

Falkenhayn therefore set about mobilizing the German economy for a long conflict. Plans were laid for large increases in production of machine guns, heavy artillery and munitions. The allocation of labor, essential raw material and foodstuffs was brought under control of the War Ministry. By these means Germany gained a march on the Allies, who were slower to recognize that fundamental changes in the nature of war were occurring. Only gradually would it dawn on them that the Great War was a peoples’ war, with the armed forces just the spearhead of a mighty national effort.

On the Western Front itself, the crude entrenchments of the early days were being expanded and improved, and here again the Germans were ahead of the Allies. The trenches they dug were deeper, better constructed and better sited than those of the British and French. Much thought and effort were devoted to the development of an integrated defense based on machine guns and artillery.

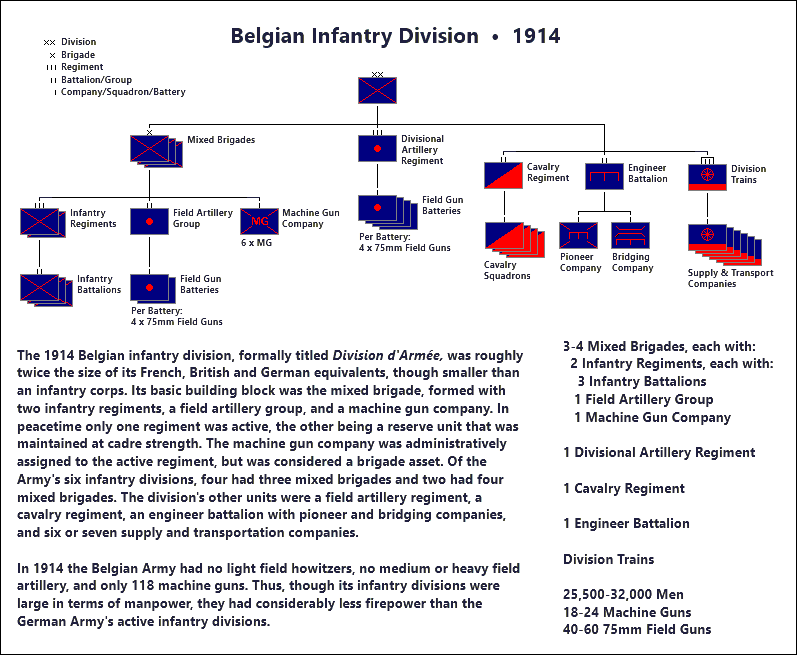

All this was in sharp contrast to the attitude of the French and British. When proposals were made to increase the British infantry’s allocation of machine guns from the paltry prewar scale of two per battalion to sixteen per battalion, senior commanders in France were loud in their objections. General Sir Douglas Haig, commanding the First Army, argued that the machine gun was “a much over-rated weapon,” and that two per battalion were more than sufficient. Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, thought that four per battalion would surely be adequate. Eventually the generals were overruled but their resistance to a weapon that had more than proved its worth in the opening round was an ominous portent.

On the Eastern Front the situation was rather different. There, thanks to the great length of the front relative to the number of troops engaged, a war of movement remained possible. Trench warfare was not unknown in the east, but it never became the dominant tactical and operational factor, as happened in the west.

For the Russian Army, the opening round in the east had ended in defeat at the hands of the Germans in East Prussia but victory over the Austrians in Galicia. These results intensified a dispute in the Russian military command that predated the war: Where to place the main effort? As Germany had “westerners” and “easterners,” the Russians had “northerners” and “southerners.” The former advocated placing the main effort against Germany, seen as the main enemy; the latter argued for placing it against Austria-Hungary, seen as easier to defeat.

This dispute had not been resolved before the outbreak of the war, so that Russia conducted two completely separate campaigns in the opening round—and nobody’s mind was changed by either the Tannenberg debacle or the victory in Galicia. The northerners alleged that the invasion of East Prussia had failed because it was undertaken prematurely, before the Russian Army was fully mobilized. The southerners offered the collapse of the Austrian armies in Galicia as proof that they had been right all along. Once again, the dispute was not resolved and the Russian Army continued to fight two separate wars, with much bickering between the commanders involved as to the allocation of material and reserves.

A more immediate problem, however, was a shortage of weapons and munitions, the Russian Ministry of War and General Staff having underestimated the rate at which both would be consumed. Prewar stocks were used up in the opening round and since no provision having been made for a large-scale conversion of industry to meet wartime needs, production was quite inadequate to cover the Army‘s ongoing requirements. The resulting shortages, serious enough in themselves, also provided the generals with a convenient excuse for their repeated failures against the Germans. But as a matter of fact, the shell shortage was never as dire as the generals alleged. Many of the defeats they sustained at the hands of the Germans could have been prevented or at least ameliorated by more sensible planning and tactics.

So Europe entered the first winter of the war. In the west, the Allies busied themselves with plans for the offensives of 1915 that would, they were confident, overthrow the German Army. In the east, Germany was preoccupied with the necessity of shoring up the Austrian front in the Carpathians, where continued Russian pressure threatened a breakthrough into Hungary that would be disastrous for the Habsburg Monarchy. Falkenhayn, resigning himself to the inevitable, therefore decided that in view of the Austro-Hungarian emergency, the main German effort for 1915 would have to be made in the east. If it could not be decisively defeated, the Russian Army must at least be neutralized. To that end, considerable forces were taken from the Western Front and transferred east. As a first step, Falkenhayn planned a limited offensive, to be launched in mid-November, with the objective of destroying Russian forces in the Polish salient.

A complicating factor for the Central Powers was the possibility—increasingly likely in view of the Austro-Hungarian emergency—that Italy would enter the war. That country had bailed out of the Triple Alliance in August 1914, alleging that Austria’s aggression against Serbia negated Italy’s treaty obligations. And though the Italian government declared neutrality, its designs on the Austrian Trentino, Trieste and the eastern Adriatic littoral were hardly a secret. Italy thus found itself in the congenial position of soliciting bids for its support in the war. Germany pressed the Austrians to yield up some territory in exchange for continued Italian neutrality, adding in an undertone that after victory it could always be taken back. The Allies offered to support Italy’s annexation of the desired territories in exchange for its entry into the war.

But for the moment the Italians hesitated, for not all political factions in Italy were in favor of war. By and large, the liberal-nationalist government and its supporters were the war hawks, while the socialists and the conservatives mostly opposed intervention. But with the string of defeats suffered by the Austrians in Serbia and Galicia, the temptation to take the plunge grew stronger and stronger.

On the Allied side, the situation was complicated by the Ottoman Empire’s entry into the war on the side of the Central Powers (2 November 1914). This development opened new theaters of war in the Caucasus against Russia and in Middle East against Britian. The resulting diversion of troops and resources from the both the Western and Easterns Front was of considerable benefit to the Germans and Austrians.

As 1914 drew to a close, however, few among the belligerents were willing to admit that militarily the war was deadlocked. With the significant exceptions of Falkenhayn on one side and of a few skeptics like Churchill on the other, the generals remained confident that with more troops and more firepower they could overcome their difficulties and achieve decisive victory on the main European fronts. In 1915, a second round of battles, west and east, would put that confidence to the test.

"Prewar stocks were used up in the opening round and since no provision having been made for a large-scale conversion of industry to meet wartime needs, production was quite inadequate to cover the Army‘s ongoing requirements."

"Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose."

Europeans still haven't learned the lesson - see Ukraine.

Great series here. We’ve lived in Belgium since 1965 (just north of Waterloo), and have wandered all over the western battlefields. Less familiar with the eastern areas, so that part of your history is especially interesting. Reading on...