Part Twelve: Opening Round in the West (3)

(For clarity, German units are rendered in italics.)

As with Tannenberg, legends cluster around the First Battle of the Marne. Celebrated incidents like the taxicabs of Paris rushing troops to the front were magnified beyond their importance by wartime propaganda, and the battle itself acquired mythic status, as attested to by the title bestowed on it: the “Miracle of the Marne.”

The facts are more prosaic. In a remarkably prescient prewar Cabinet paper Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, set down his ideas about the likely course of a German offensive against France. He foresaw a forty-day campaign with a German advance to the vicinity of Paris culminating in a decisive battle that would check the invading armies and throw them back. Churchill pointed out that as the invaders advanced their front would become wider, their communications more tenuous, the security of the area in the rear of their front-line forces less certain. Troops would have to be detached to mask fortresses, guard rail lines, occupy captured cities, etc. Casualties would further thin the Germans’ ranks, and fatigue would reduce their battle capacity.

But what came so clearly to Churchill in peacetime was less easily perceived by those caught up in the storm and stress of battle. As August gave way to September and the armies of the German right wing drew steadily closer to Paris, many leaders on the Allied side took counsel of their fears. The French government decamped to Bordeaux, leaving Paris to its military governor, General Joseph Gallieni, whose orders were to place the national capital in a “state of defense.” Gallieni, who was General Joffre’s designated successor as commander-in-chief in case of the latter’s death or incapacity, demanded three regular corps—some six divisions—to bolster his scratch force of Territorial troops. This Joffre refused—though later, with the Germans at the gates of the capital, he changed his mind and placed the newly raised Sixth Army under Gallieni’s command.

The disastrous outcome of the Battle of the Frontiers and the Great Retreat had shaken the confidence of soldiers and civilians alike. Prominent among those exhibiting signs of stress was the commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), Field Marshal Sir John French. The hard-fought Battle of Mons with its many casualties had shocked him, the Great Retreat had depressed him, and his suspicions about the intentions of his French allies had metastasized into defeatism. Late in August he informed the British government that he intended to take the BEF out of the line entirely, withdrawing it to the Channel coast in anticipation of an evacuation from France.

In London, this missive was received with consternation: Prime Minister Asquith and his Cabinet colleagues were aghast at the suggestion that Britain should abandon its embattled ally. The Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, was dispatched to France with peremptory orders: The BEF was to stay in the fight and conform to Joffre’s general plan of campaign. But Sir John French's nervousness was understandable enough, for on the face of things the German offensive was unfolding according to plan. By 29 August First Army had advanced to within fifteen miles of Paris and its commander, General Alexander von Kluck, was confident of victory. His immediate opponent, the French Fifth Army (now commanded by General Franchet d'Esperey), had been badly knocked about and Kluck judged that one final thrust would lead to the collapse of the French left flank and the fall of Paris.

Supposedly Kluck was under the orders of his left-flank neighbor, General von Bülow, commanding Second Army—this to ensure that the advance of the right wing was properly coordinated. The Chief of the OHL, General Helmut von Moltke, far away in Luxembourg, had delegated authority to Bülow in compensation for his own inability to control the battle. Kluck, however, took scant notice of this technicality.

Though First Army remained on the move, the advance of Second Army had stalled out to the east of Paris, just south of the Marne River, and Bülow was becoming concerned about the security of his right flank. He wanted First Army to sidestep left, closing the gap that had opened between the two armies. Kluck paid little heed to Bülow’s calls for support: Scenting victory, he remained intent on his quarry: the tottering Fifth Army. But now the inexorable logic of events forced the First Army commander’s hand.

On 30 August Kluck made a fateful decision: Seeking to turn Fifth Army’s left flank, he once more altered his army’s line of advance. Schlieffen’s grand design had the German right wing enveloping Paris to the north and west; Kluck now proposed to pass to the east of the French capital. And there can be little doubt that had his ploy succeeded the French Army would have sustained a heavy defeat, with the loss of Paris and perhaps even of the war. Nor was Kluck’s turn unwelcome to Bülow, who saw that it would close the gap, now thirty miles wide, that so worried him. It seemed indeed that victory was within the Germans’ grasp.

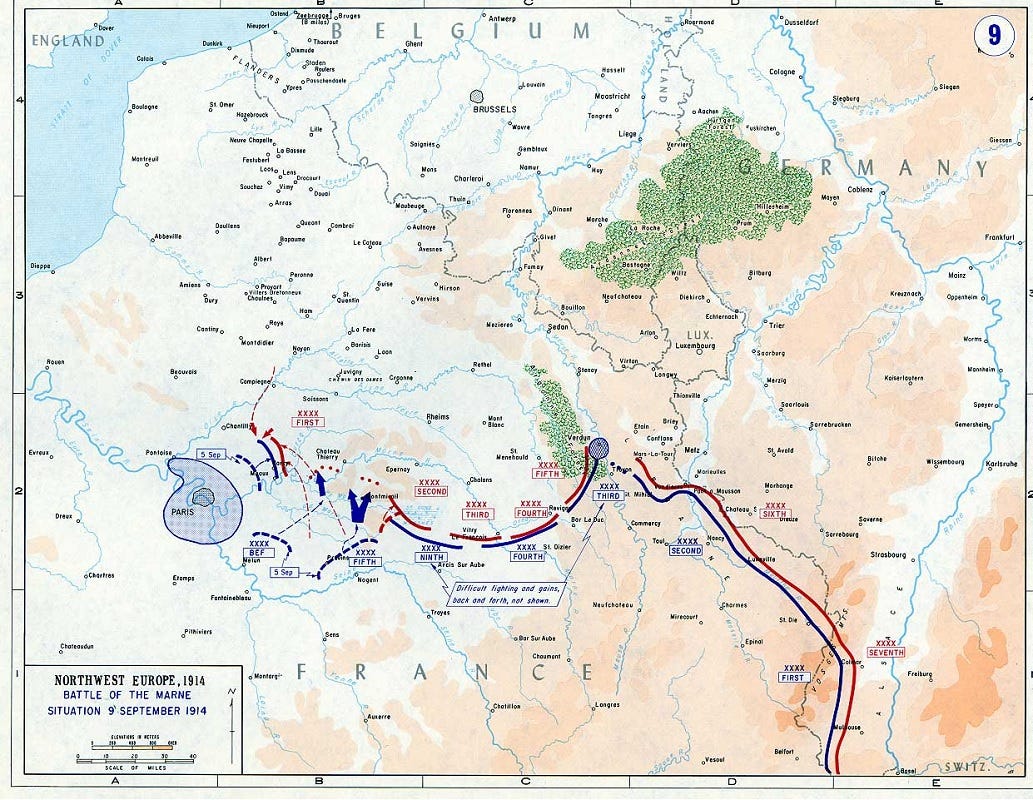

But it was not to be. For as Winston Churchill had foreseen, the German advance became more and more disjointed as casualties, fatigue and the fog of war exacted their toll. When Kluck made his turn, he had no inkling of the presence near Paris of the new Sixth Army. The French, however, were better informed: Radio intercepts, confirmed by air reconnaissance, had alerted Gallieni to the German change of front. “They offer us their flank!” he exclaimed, and with Joffre’s agreement he ordered Sixth Army to attack. It did so on 5 September, striking First Army’s exposed right flank. This was the opening engagement of the Battle of the Marne.

A commendably prompt counterattack on 6 September by IV Reserve Corps, the right-flank corps of First Army, stopped Sixth Army in its tracks and drove it back. Kluck, now alert to the danger, turned his army to face west, a necessary move but one that prevented the closure of the gap between it and Second Army. The latter was by now in a precarious position. On 8 September Joffre ordered the reinforced Fifth Army to join the attack, striking Bülow’s right flank, driving it back and widening the fatal gap. Into it marched the BEF. Brushing aside such German cavalry patrols as they encountered the British troops reached and crossed the Marne, and by 10 September they held a bridgehead six miles deep. Second Army’s flank had been turned. Farther east, attacks by the French Fourth and Ninth Armies added to the pressure on the German right wing.

Deepening anxiety at OHL about the situation at the front had already led Moltke to dispatch to the armies a staff officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Hentsch. He was given instructions to ascertain the situation and, if necessary, to issue orders in OHL’s name. It may seem remarkable that an officer of modest rank was given such powers, but this was a feature of the German general staff system. Arriving at Bülow’s headquarters on 8 September, even before the BEF had reached the Marne, he concluded that Second Army was in danger of encirclement, and that an immediate retreat of the entire German right wing was necessary. Kluck, whose army was still fighting well, protested that victory was just around the corner but Hentsch, making use of the authority he had been given, carried his point. Orders were issued for a general retirement to the line of the Aisne River. Thus was the Battle of the Marne decided in favor of the Allies.

The German armies retreated in good order, not too closely pursued by the French and British, who were as tired and worn out as their opponents. On 13 September the Germans reached the Aisne and there they established an entrenched position: the first appearance in the West of a defensive system that would soon become ubiquitous. The armies of the German left wing were ordered to desist in their attacks around Verdun and give up troops to reinforce the Aisne position.

Kluck’s turn is usually represented as the cardinal error that ruined Schlieffen’s master plan. But in fact, that plan had already gone wrong when Second Army became stuck while First Army continued to advance, thus opening the gap between them. Once that happened it became impossible for Kluck, with both flanks unprotected, to pass north and west of Paris. Somehow that gap had to be closed, either with fresh troops or by a move to the east on the part of First Army. Had it been closed, the Germans might still have prevailed. But the presence of the French Sixth Army near Paris scotched that possibility. Its attack on 5-6 September, though tactically unsuccessful, compelled Kluck to halt his army and face west. The gap between First and Second Armies remained open, soon to be exploited by the BEF and Fifth Army. Lieutenant-Colonel Hentsch, who later was much maligned for his role in the battle, did no more than bow to the inevitable when he ordered the retreat of the German right wing.

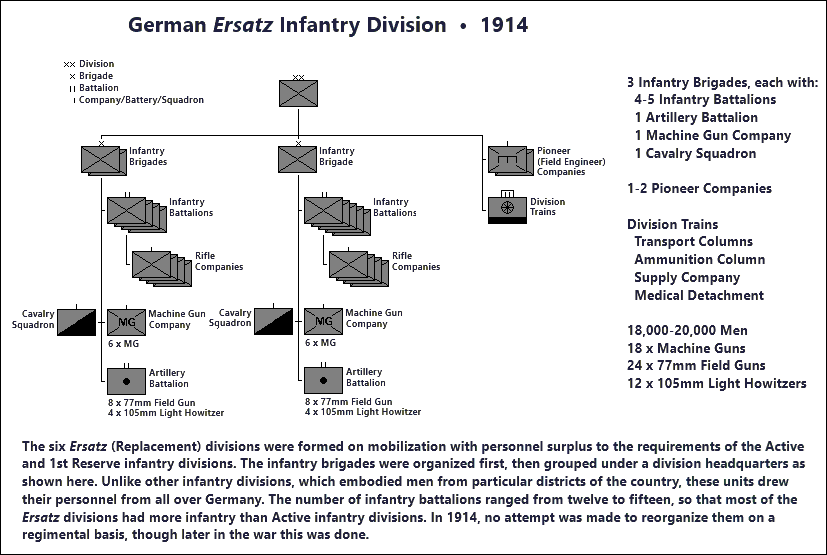

The failure of the great offensive had a shattering effect on Moltke. He is said to have reported to the Kaiser, “Majesty, we have lost the war.” Shortly thereafter he suffered a nervous breakdown. For fear that the news of his collapse would depress national morale, he was not immediately relieved as Chief of the OHL. But all business was taken out of his hands and entrusted to his eventual successor, General of Infantry Erich von Falkenhayn, the Prussian Minister of War. For a month the wretched Moltke lingered on at OHL, his presence an unwelcome reminder of the victorious hopes that had been dashed on the Marne. Later he was given command of the Replacement Army (Ersatzheer), responsible for mobilizing reserves, raising new units, and training conscripts. But his health continued to deteriorate, and he died in June 1916.

Thought Germany’s bid for a quick victory had failed, the war of movement in the west was not yet at an end. Beyond Paris the flanks of the opposing armies remained open. It was the possibility, recognized by both sides, that the enemy’s flank might yet be turned that led to the misnamed Race to the Sea: a series of engagements that extended the front from the Aisne line to the Channel coast in Belgium. And there, around the town of Ypres, was fought the first of those sanguinary battles by which the Western Front acquired its sinister reputation.