Part Eight: Opening Round in the East (3)

(For clarity, German units are rendered in italics.)

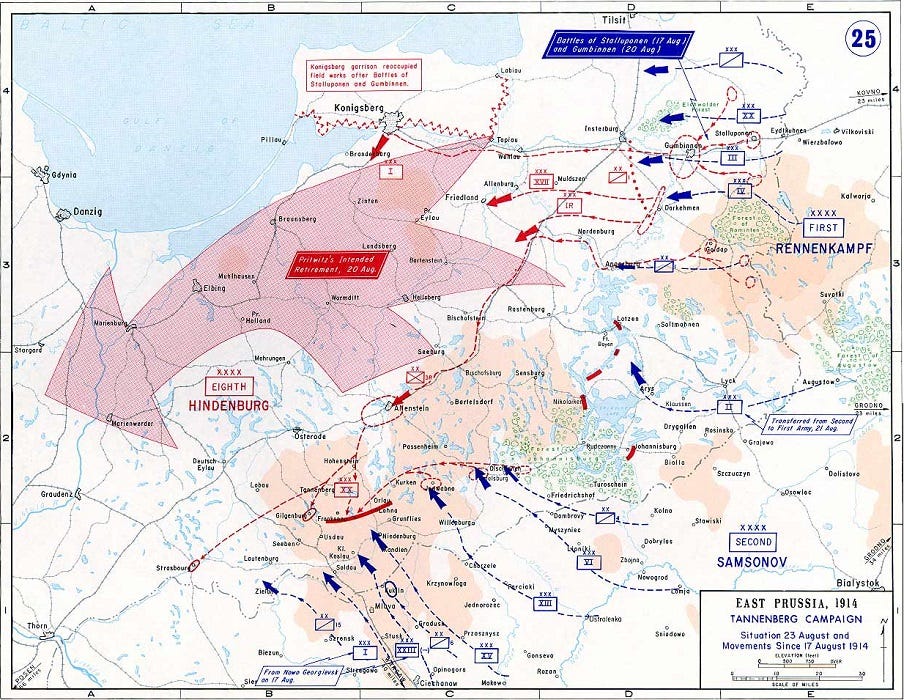

As the Austro-Hungarian armies marched across Galicia toward their rendezvous with disaster, Russian troops commenced the invasion of East Prussia. General of Cavalry Pavel Rennenkampf’s First Army (four corps and five cavalry divisions) crossed the frontier on 17 August, rather earlier than the Germans had expected. This was the northern prong of the Russian offensive, directed against Königsberg. On 18 August its vanguard was repulsed with heavy casualties by Eighth Army’s I Corps (Lieutenant-General Hermann von François) around the town of Stallupönen, some ten miles inside the East Prussian border. But he had attacked without orders and when Colonel-General Maximilian von Prittwitz und Gaffron, commanding Eighth Army, heard what had happened he ordered François to break off the battle and retire. Prittwitz intended to concentrate his forces some ten miles farther west, around the town of Gumbinnen. Not without protest, François complied with the Eighth Army commander’s orders. Once his corps vanished from their front, the Russians resumed their advance.

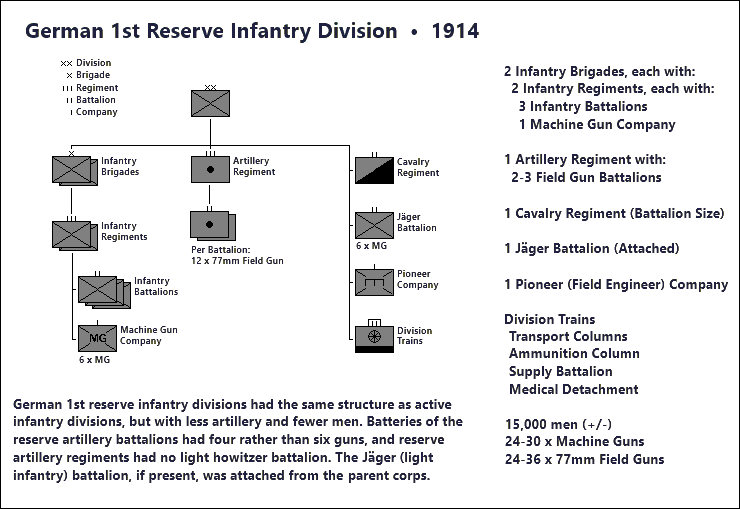

By 20 August, Prittwitz had the bulk of his army drawn up in the vicinity of Gumbinnen: I Corps on the left, XVII Corps (Lieutenant General August von Mackensen) in the center and I Reserve Corps (Lieutenant-General Otto von Below) on the right—six infantry divisions and a cavalry division in all. Intercepted radio messages (the Russians were blithely transmitting in the clear) revealed that Rennenkampf had declared a rest day for his army on 20 August, so Prittwitz decided to attack.

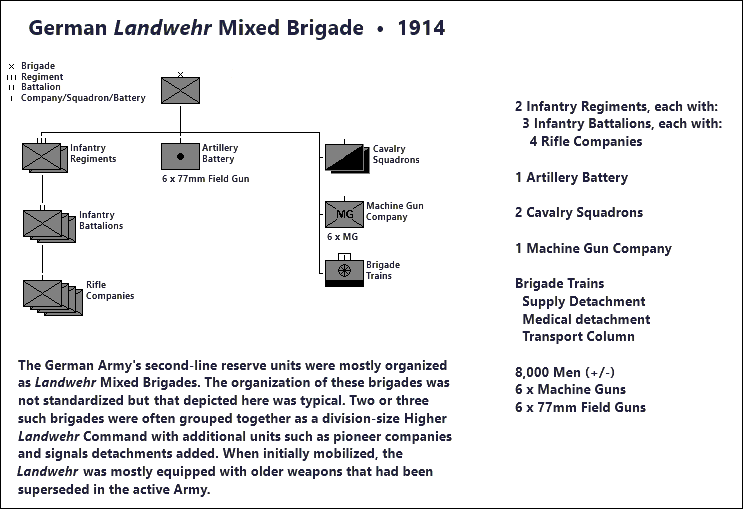

On the left after a hard fight, I Corps gained the upper hand over Russian XX Corps but in the center things went wrong. Mackensen committed his XVII Corps to a frontal attack that broke down after heavy fighting. Under violent fire from the Russian artillery, the German infantry panicked and fled. Prittwitz thereupon ordered I Corps and I Reserve Corps to retire also. That evening he telephoned Moltke at OHL to announce that Eighth Army had been defeated at Gumbinnen and would probably be compelled to retreat behind the Vistula River, abandoning East Prussia completely. Prittwitz’s alarm was compounded by the news that Russian Second Army (five corps and three cavalry divisions under General of Cavalry Alekesander Samsonov) had commenced its attack out of the Polish salient, moving northwest into East Prussia. There was nothing south of the Angerapp-Stellung to oppose the Russians except the two divisions of XX Corps (Lieutenant-General Friedrich von Scholtz) and some Landwehr troops. Fearing that Second Army’s advance would cut the rear communications of the German forces standing against First Army, Prittwitz succumbed to panic. Late that evening he telephoned Moltke again, confirming his decision to quit East Prussia.

Though the possibility that East Prussia might be lost had always been recognized, Moltke shrank from its consequences. To yield the ancient heartland of the Hohenzollern monarchy in the first weeks of the war would deal an enormous psychological blow to the Army and the nation. Agitated protests poured into OHL from East Prussian landowners and even from the Kaiser himself. General von François, who believed that the situation was not as dire as Prittwitz supposed, protested directly to the monarch against the proposed withdrawal. On 21 August, therefore, Moltke decided that Prittwitz and his chief of staff, Major General Alfred von Waldersee, had to go.

Looking around for suitable replacements the Chief of Staff’s eye fell on one Major-General Erich Ludendorff, a man who had recently made his mark in the west, during the siege and capture of the Belgian fortress of Liege. But Ludendorff was too junior to be given command of Eighth Army; he would be made its chief of staff. For the army’s new commander Moltke resorted to the retired list. From it he selected the 67-year-old Colonel-General Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg, a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War with a solid reputation. In response to Moltke’s telegram inquiring when he could report for duty, Hindenburg responded tersely, “Am ready.” Wearing the obsolete blue uniform of a Prussian general (he had not had time to be fitted for the new field gray) Hindenburg joined Ludendorff on the train that was to carry them both east.

Meanwhile, ignorant of the fact that he was about to be sacked, Prittwitz had somewhat recovered his balance. Thanks to aerial reconnaissance, supplemented by the Russians’ habit of transmitting radio messages in the clear, he had good information about his opponents’ dispositions and intentions—knew, for example, that despite having gotten the better of the fighting at Gumbinnen, First Army was doing nothing. The offensive into East Prussia had been launched before the Russian armies’ supply services were fully mobilized—this in response to insistent French pleas for early action—and Rennenkampf judged that his army’s logistical problems ruled out an immediate advance. Making matters worse, a difference in gauges meant that Russian trains could not use the East Prussian rail net. It was thus proving doubly difficult to bring forward the rations, fodder, ammunition and replacements that his army needed. Farther south, Samsonov’s Second Army was experiencing similar problems as it marched into East Prussia.

Armed with this knowledge his staff proposed, and Prittwitz agreed, to leave only a thin screen of cavalry and Landwehr troops facing First Army. The bulk of Eighth Army would move south to confront Second Army, an operation made possible by efficient staff work and the well-managed East Prussian rail net. This was the situation on 23 August when Hindenburg and Ludendorff arrived at Eighth Army headquarters—bearing the news to Prittwitz and Waldersee that they had been dismissed. Thus was the stage set for the storied Battle of Tannenberg.

"...a difference in gauges meant that Russian trains could not use the East Prussian rail net."

I have read variations of this in every account of Eastern Front fighting (1st and 2nd world wars).

Every officer (on both sides) knew this.

Converting to the other gauge is tedious, time consuming, and requires a depot, but not technically difficult.

It seems to me that the Russians could have bought 30 older trains (engines and carriages) from the French and stored them in Poland (no secrets divulged since everybody knew a Russian invasion was in the cards).

15 trains supplying each Russian army might have alleviated supply issues.

On the other hand "Everything in war is simple, but the simplest thing is difficult."