The War at Sea: Strategic Imperatives

Note on British Naval Appointments

At the time of the Great War, the civilian head of Britain’s Royal Navy (RN) was the First Lord of the Admiralty, a senior member of the cabinet who headed the Board of Admiralty, the government ministry charged with administrative and operational control of the RN. It should be explained that the Board of Admiralty embodied the duties and responsibilities of the Lord High Admiral, one of the great and ancient offices of state. The term Admiralty referred to the powers of this office. In times past it had usually been held by the monarch or another member of the royal family, but since 1832 it had been “in commission,” its powers delegated to the Board of Admiralty, whose members were thus titled “the Lord Commissioners for Executing the Office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom.” In August 1914, the First Lord of the Admiralty was Winston Churchill.

The flag officer serving as professional head of the RN was titled First Sea Lord; his duties corresponded to those of a chief of staff. The senior staff officers under him were titled Second Sea Lord, Third Sea Lord, etc., each with specific responsibilities. The Third Sea Lord, for instance, was responsible for ship design, ordnance, naval construction, RN dockyards, and related material matters. In August 1914, the First Sea Lord was Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg.

The strategic imperatives governing the Great War at sea found their focus in the central standoff between Britain’s Royal Navy and Germany’s Kaiserliche Marine.

For Britain, a globe-spanning imperial power heavily dependent on imports to feed both industry and population, freedom of the seas was the sine qua non of victory, and naval supremacy was its guarantee. Throughout the war, therefore, the maintenance of naval superiority was the Royal Navy’s overriding priority. This explains why the hoped-for clash between the main battle fleets didn’t happen until May of 1916 and why, when it did, the outcome seemed indecisive.

When war broke out in 1914, both the Royal Navy’s leaders and the British public looked forward to an early fleet action in the North Sea: a triumphant super-Trafalgar. But the man newly appointed to command the Grand Fleet (as the Home Fleet was renamed when war came) took a sober, more realistic view. Admiral Sir John Jellicoe was a protégé of Jackie Fisher, the reforming First Sea Lord between 1904 and 1911 (and soon to be reappointed to that post). In August 1914 Jellicoe was serving as Second Sea Lord, responsible for manning, mobilization, and other personnel matters. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, selected him to replace the incumbent commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Sir George Callaghan, who was verging on retirement. Churchill felt that a younger, more dynamic commander was needed, but his decision caused much controversy. Callaghan was greatly admired throughout the service and even Jellicoe protested to the First Lord over his replacement—to no avail.

John Jellicoe himself was universally regarded as one of the ablest men in the RN; his appointment to command the Grand Fleet was a sound move on Churchill’s part. And it was a fortunate one for Britain because Jellicoe, despite his natural desire to bring the German High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte) to battle, was in no doubt of the risks involved. He knew that his primary responsibility as commander of Britain’s principal naval force was to preserve its power. While the Grand Fleet remained in being, dominating the North Sea and bottling up the German fleet, the freedom of the seas would rest with Britain and its allies. And more: British control of the exits from the North Sea would automatically impose blockade on Germany—strangling its overseas trade and cutting off its access to foreign sources of raw materials.

As a glance at the map shows, in the face-off between the Grand Fleet and the Hochseeflotte geography favored the former. Great Britain lay astride Germany’s routes out of the North Sea, into the Atlantic. The Strait of Dover and the English Channel were impassible to German shipping and the northern exits between the Orkney and Shetland Islands could easily be closed by minefield and patrols. The Grand Fleet’s war station was at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. Its presence there, and its frequent sorties into the North Sea, gave security to the patrols that enforced the blockade.

In short, the Grand Fleet’s mere existence secured the basic objectives of British naval strategy—a fact of which Jellicoe was only too well aware.

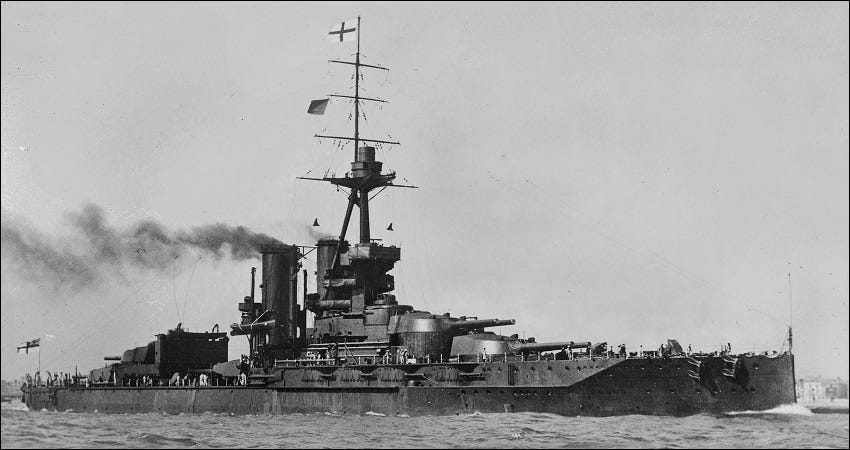

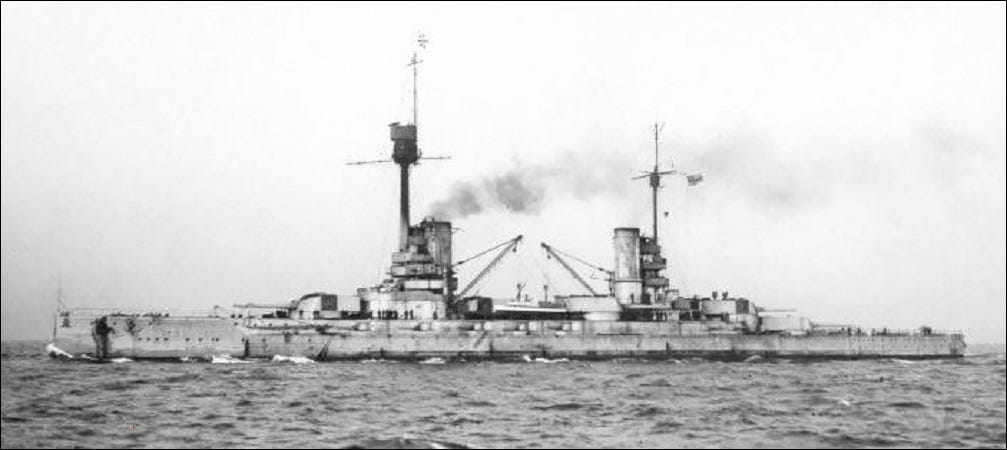

In August 1914 the Royal Navy in home waters outnumbered the Kaiserliche Marine by twenty-one dreadnought battleships plus four battlecruisers to fourteen dreadnought battleships plus five battlecruisers. The RN soon acquired three additional dreadnoughts: two built in Britain for the Ottoman Empire, seized in August 1914, and one built for Chile, purchased later in the year. Both navies had additional battleships and battlecruisers under construction, but work was slowed or stopped on all but those that were close to completion. Initially both battle fleets included some pre-dreadnought battleships, but these were quite outclassed by the dreadnoughts and most of them were soon relegated to secondary duties.

Jellicoe worried constantly that some mishap—battleships torpedoed by submarines, or sunk in a minefield, or caught unsupported by a superior German force—might pare down the Grand Fleet’s margin of superiority. These anxieties influenced his conduct of operations in the North Sea from the beginning of the war to May 1916, when the two battle fleets finally clashed at Jutland. In August 1914 Jellicoe carefully explained to Churchill the dangers of a too-aggressive policy. The obvious German strategy would be gradually to even the odds by sinking a ship here and a ship there. Therefore, said Jellicoe, he would “decline to be drawn” into a possible submarine ambush or onto a suspected minefield. Churchill, despite his passionate desire to bring off a decisive fleet engagement, accepted this reasoning. At all costs, the Grand Fleet must remain in being.

And in fact, German naval strategy at the beginning of the war envisioned just such a gradual evening of the odds: Early operations in the North Sea were intended to provoke a reaction from the British, presenting opportunities for isolating and destroying some portion of the Grand Fleet. To that end, the Hochseeflotte’s First Scouting Group with its high-speed battlecruisers conducted a number of bombardments of British North Sea coastal towns in late 1914 and early 1915. The idea was to lure out the Grand Fleet’s Battlecruiser Squadron, which would then be engaged by the whole Hochseeflotte, lurking just over the horizon. But the desired ambush never came off, thanks to the fog of war and uncertainty that obscured naval operations at a time when radar did not exist and air reconnaissance was in its infancy.

Elsewhere, in the Mediterranean, the Pacific and the South Atlantic, the early days of the naval war witnessed many dramatic incidents, including a stinging defeat for the Royal Navy that was soon avenged. But at sea as on land, the bedrock strategic imperatives of those early days set up the pattern of the Great War.

Banal comment, but consider the enormous expenditures by Germany and how little it brought the Germans (other than firmly convincing England that German was the greatest threat).

As we look at the American Navy today and the potential for a maritime war with China, we have to wonder about the wisdom of some of our naval expenditures - have we spent our limited resources wisely?