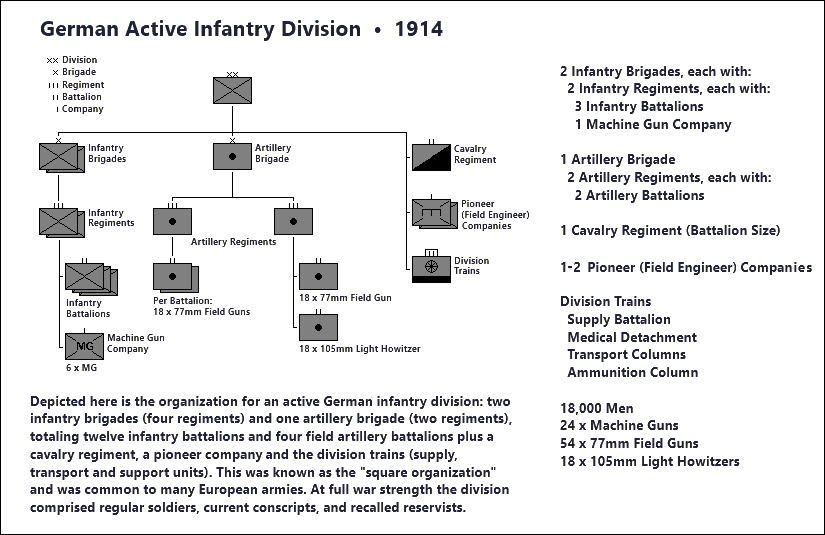

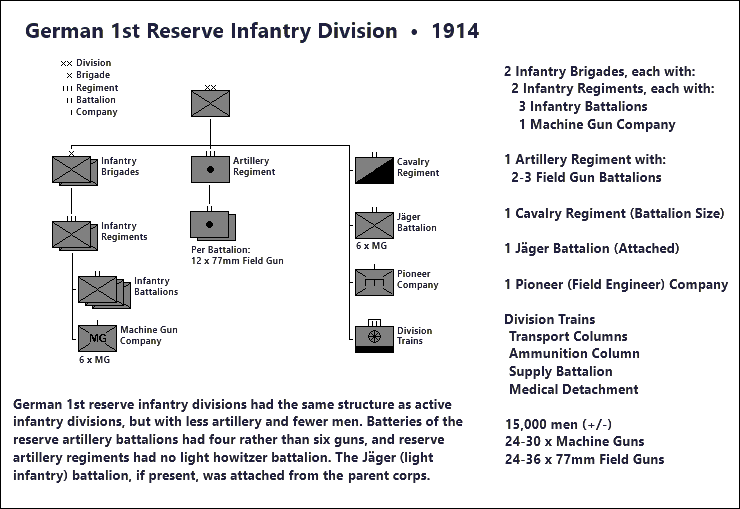

Throughout the Great War, the infantry division was the mainstay of the armies of all the belligerents. With a few exceptions, in 1914 all were organized as “square” divisions with two infantry brigades, each brigade with two infantry regiments, each regiment with three or four battalions. To these were added a field artillery brigade with two regiments, a battalion-size cavalry regiment as the reconnaissance element, one or two pioneer (combat engineer) companies, and the division trains (supply, transport, signal, and medical units).

Almost all of the active and reserve infantry divisions mobilized by the German Army in August 1914 were organized in this manner. Only the six Ersatz (replacement) infantry divisions deviated from the square division template, though later they were reorganized along that line. German infantry regiments had three battalions, for a division total of twelve, armed predominantly with rifles. Each regiment also had a machine gun company (6 x MG), for a divisional total of twenty-four. This allowance worked out to one machine gun for every five hundred riflemen. The machine gun was the MG 08, a sled-mounted, water-cooled, belt-fed weapon.

As for artillery, active divisions had 54 x 77mm field guns and 18 x 105mm light field howitzers in their artillery brigade. Reserve infantry divisions had only a field artillery regiment with 24 x 77mm field guns, and in some cases their infantry regiments had only a machine gun section (2 x MG). Personnel strengths were 18,000 for active divisions and 15,000 for reserve divisions, approximately eighty percent of whom were riflemen.

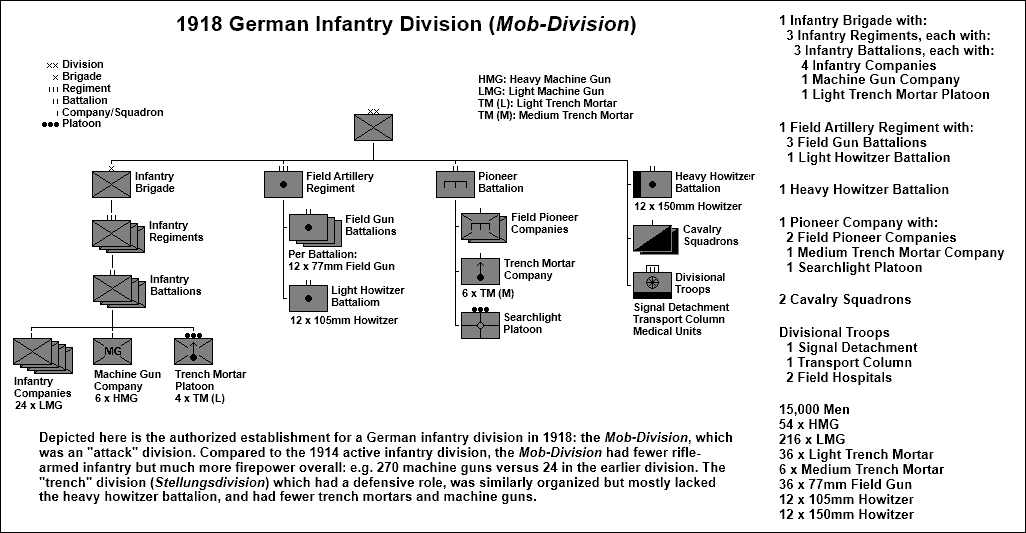

By 1918, however, the German infantry division had evolved into quite a different type of combat unit, with less manpower but significantly more firepower than the 1914 square division. Two factors combined to drive this process: the need to make the most efficient possible use of manpower, and the addition of new weapons and specialist units required for modern war, especially on the Western Front.

A revision of the infantry division’s basic structure was decreed in late 1915, the square configuration giving way to a “triangular” structure. One infantry regiment was deleted and one infantry brigade headquarters was dissolved, leaving three infantry regiments under the remaining brigade headquarters. The regiments were reinforced with additional machine gun sections on an as-needed basis, and in the autumn of 1916 these sections were combined to provide each regiment with three machine gun companies, one per battalion, for a divisional total of 54 x MG. Also organized at this time were some ninety separate Maschinen-Gewehr-Scharfschützen-Abteilungen (machine gun sharpshooter battalions), three companies strong, with 18 x MG. These battalions were attached to divisions as needed. By late 1916, the Army had about 12,000 machine guns on hand as against the 1914 total of 1,600.

In addition to the machine gun company, each battalion also acquired a mortar platoon with four light mortars, called Minenwerfer (mine thrower) in German. Though this weapon had a comparatively short range, its high-angle trajectory made it very effective in trench warfare.

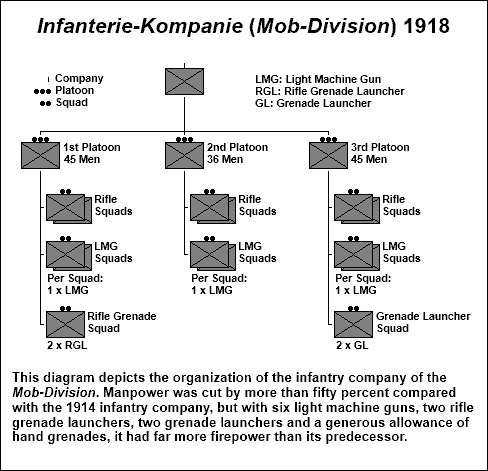

Also in 1916, a light machine gun, the MG 08/15, was introduced. This weapon was a modification of the MG 08, with a sling, buttstock, pistol-grip trigger and air-cooled barrel. The initial scale of issue was three per infantry company, for a divisional total of 108, though it was not until late 1917 that every infantry company was so armed. By early 1918, the scale was doubled to six per company, for a division total of 216, which worked out to one machine gun for every fifty-five riflemen.

The division’s thirty-six infantry companies were also reorganized. In 1914 a company had 243 men, divided into three platoons of eighty-one men each, armed exclusively with rifles. By early 1918 an infantry company had three platoons, one with two rifle squads, two LMG squads and a rifle grenade squad (45 men); one with two rifle squads and two LMG squads (36 men); and one with two rifle squads, two LMG squads and a grenade launcher squad (45 men). The grenade launcher, called a Granatenwerfer or grenade thrower in German, was a lightweight weapon with a range of about three hundred yards. Rifle grenades and the grenade launcher supplemented hand grenades, of which there were two types: the stick grenade (blast effect) and the egg grenade (fragmentation effect.)

The divisional field artillery brigade was downsized to a regiment of four battalions. The battalions’ firing batteries were reduced from six to four field guns or howitzers, for a divisional total of 36 x 77mm field guns and 12 x 105mm light field howitzers. By early 1918, this was the standard for all infantry divisions on the Western Front. The surplus guns and howitzers thus made available were used to form eighty independent field artillery regiments that could be allocated to divisions as necessary. Many infantry divisions also received a heavy artillery battalion, usually armed with 150mm howitzers. Divisions on the Eastern Front, where serious fighting was over by the end of 1917, had much less artillery and in some cases none at all.

Finally, the divisional pioneer company was expanded into a battalion consisting of two pioneer (combat engineer) companies, a medium trench mortar company (6 x Minenwerfer), and a searchlight platoon.

These changes cut the infantry division’s strength from the 1914 average of 18,000-15,000 to about 15,000. However, the reduction in rifle strength was more than offset by the great increase in machine gun strength, from twenty-four in 1914 to 270 by 1918. In like manner, the reduction in artillery strength was offset by the addition of forty-two light and medium trench mortars.

By 1918 on the Western Front, the German field armies embodied two infantry division types: the “attack” division (Angriffsdivision or Mob-Division) and the “trench” division (Stellungsdivision). They had the same basic structure, but the attack divisions received the latest equipment and the best-quality manpower. The trench divisions were manned by older men, and many did not receive the full allowance of machine guns, trench mortars and artillery.

Though they were not organic to the infantry divisions, mention should also be made of the special infantry assault battalions (Sturmabteilungen) that first appeared in 1915 and by 1918 were fully integrated into the combat organization of the German Army. These battalions were formed with the youngest, fittest soldiers, and they received extensive training in infiltration tactics. On the attack, these stormtroopers (Stoßtruppen) constituted the spearhead, moving forward in company or platoon strength, bypassing centers of resistance whenever possible, making for the enemy’s vulnerable rear areas. Their officers and NCOs were expected to display initiative, seizing opportunities without reference to higher headquarters. Behind them came larger battlegroups to eliminate surviving enemy strongpoints and consolidate the ground gained in preparation for the commitment of the reserves.

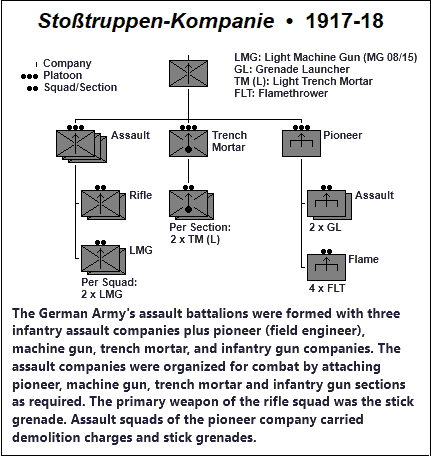

The Sturmabteilung was a combined arms unit, usually consisting of three companies, each company with three infantry assault platoons, a light trench mortar platoon, and an assault pioneer platoon. The infantry assault platoons each had two rifle squads and two light machine gun squads, the trench mortar platoon had four light trench mortars, and the assault pioneer platoon had two assault squads carrying demolition charges, and a flamethrower squad. The main weapon of the rifle squads was the stick grenade. Some battalions also had an assault artillery battery with four or six light mountain howitzers or 77mm field guns for direct fire support. The assault battalions were pooled at the field army or corps level and allocated to divisions as required. Usually, divisions tasked to conduct the initial attack had an assault battalion assigned to them.

The evolution of the German infantry division from 1914 to 1918 reflected the development of new tactics and operational methods to cope with the special demands of trench warfare on the Western Front. These were, of course, applicable to the Eastern and Italian fronts as well and indeed, some of the German Army’s new offensive tactics and techniques were tried out in those theaters of war before 1918. A fuller description of that tactical evolution will be the subject of a subsequent article.

Your comment about the increase in firepower resonates through every military.

No military ever had enough firepower (with the exception of the US in the Gulf Wars).

Both the number of weapons and the amount of ammunition needed is usually underestimated.

The Ukraine War is a prime example, with artillery and ammunition being in short supply (especially glaring is the western European situation, where their militaries equipped for a war of a few weeks against a numerically limited enemy).

In crass terms, most militaries prepare to fight Luxembourg, even when Russia is the likely enemy.