Part Three: The Myth of the Master Plan

In August 1914 those iconic stigmata of the Great War—the trenches, the barbed-wire entanglements, the mud, all the ingredients of the hideous death match to come—were still over the horizon. The conflict began as a war of maneuver, and the battles fought in those first few months prepared the ground for a four-year stalemate.

It was Germany’s Schlieffen Plan—or rather its failure—that set the pattern for the war in the west. Field Marshal Count Alfred von Schlieffen, Chief of the Großgeneralstab (Great General Staff) from 1891 to 1906, grappled for fifteen years with the military dimensions of a scenario that Germany’s leaders had long dreaded: a two-front war.

It was a frightful prospect. To the west of the Reich lay France, nurturing bitter memories of the humiliation of 1871, meditating upon revenge. To the east loomed Russia, smarting from past slights, maturing vast ambitions. In Bismarck’s day his diplomatic sleight-of-hand had prevented the iron ring from closing around Germany, the keynote being to keep France isolated by preventing a Franco-Russian alliance. That meant staying on friendly terms with the eastern colossus despite the tensions between Germany’s ally, Austria-Hungary, and Russia over Balkan issues, a balancing act that the Iron Chancellor managed with some difficulty. But after Bismarck’s retirement his policy was abandoned—clearing the way for a Franco-Russian military alliance, which was formalized in 1894.

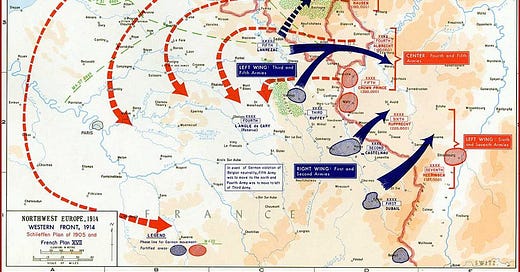

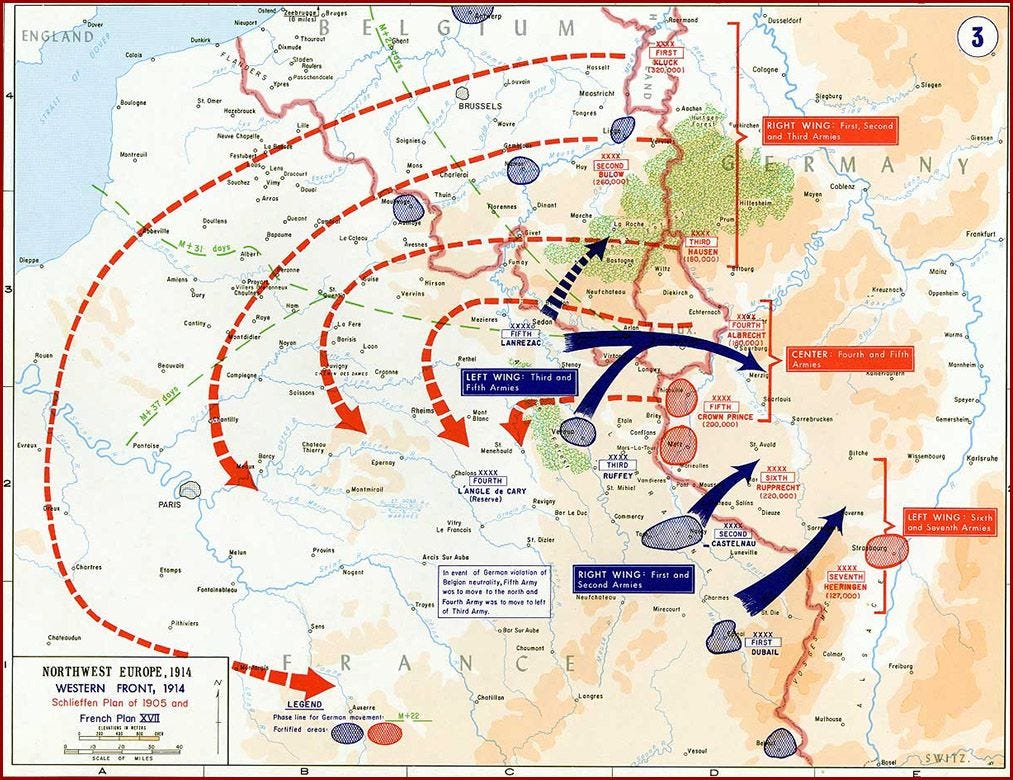

Once diplomacy failed and the nightmare of encirclement was upon them, the Germans fell back on military solutions. These, as formulated during Schlieffen’s tenure, took the form of various deployment (Aufmarsch) plans, each specific to a particular contingency. For example, Aufmarsch I West was his variant for a war between Germany and France with Russia remaining neutral. It envisioned an offensive with the bulk of the German Army massed on the right, moving through Belgium and the southern Netherlands, down the Channel coast, crossing the Somme and Seine rivers, wheeling north and south of Paris. The enemy’s left flank was thus to be shattered in a series of encounter battles, culminating in the annihilation of the French Army. The map at the head of this article depicts Schlieffen’s original concept of this operation.

He deemed the march through Belgium necessary because only in that way could the full strength of the German Army be brought to bear: Along Germany’s border with France, the space needed for such a deployment was not available. Between Belgium and Switzerland, the French had constructed a series of strongly fortified positions, so sited as to “canalize” any German offensive, narrowing its front and rendering its flanks vulnerable to counterattack. Moreover, these French defenses could not themselves be outflanked without, at the minimum, moving through Luxembourg and southern Belgium.

But if Belgian neutrality was to be violated, there seemed no reason to limit the operation to the southern portion of that country. To make an envelopment of the French left flank effective, the whole of Belgium must be used as the German right wing’s deployment area. Only in that way could the full power of the German Army be brought to bear.

Schlieffen thus proposed to concentrate the bulk of his forces on his right, while holding his left with minimal forces. He discounted the dangers of a French offensive across the common border, reasoning that it would facilitate Aufmarsch I West in the manner of a revolving door: The harder the French pushed against the German left wing, the more surely and swiftly the German right wing would descend on their left and rear.

Even so, Schlieffen was dubious about the prospects for success by offensive action. He noted that the German Army was too small (seventy-nine divisions in 1914) to carry out the great right-flank march; ninety-six divisions, he thought, was the minimum requirement. But such an increase in the size of the Army appeared impossible: The Reichstag would not give the necessary money, while the naval program so favored by Kaiser William II competed with the Army for available funds.

But Aufmarsch I West was only one of four deployment plans available to the German Army and the situation on which it was predicated—Russian neutrality in a Franco-German war—was considered the least likely. General Helmuth von Moltke, nephew of the great Moltke, who replaced Schlieffen as Chief of Staff in 1906, at first favored Aufmarsch II West, the plan for a war pitting Germany and Austria-Hungary against France and Russia. It was assumed that in that case both France and Russia would launch offensives after their mobilizations were complete. Aufmarsch II West therefore allotted four-fifths of the Army against France and one-fifth against Russia. In the east, the German and Austro-Hungarian armies would stand on the defensive. In the west the Germans would mass their forces against the attacking French, first checking the enemy's offensive, then launching a counteroffensive. After its successful conclusion, about a quarter of the Army in the west would go east to join the Austrians in a counteroffensive against the Russians.

Aufmarsch II West was based on Ermattungsstrategie: the “strategy of exhaustion.” Moltke and his General Staff colleagues had come to doubt that the alternative, Vernichtungsstrategie, the “strategy of annihilation,” was feasible in the age of mass armies. But by standing on the strategic defensive and winning battles on the tactical offensive, Germany might hope to create a diplomatic situation leading to a negotiated peace on favorable terms. In 1906, with the Russian Army in a shambles after its drubbing in the Russo-Japanese War and the country itself reeling from the shock of the 1905 revolution, this strategy appeared to be Germany’s best military option. Owing to Russia’s size, sparse rail net, administrative inefficiency and social instability, the mobilization of its army required at least two months: about twice as long as German and French mobilization. There would be ample time, therefore, for Germany to win the defensive battle against France in the west, and then to redeploy forces to the east against Russia. Moltke also counted on the German Army’s qualitative superiority for success on the battlefield.

But with the passage of time the assumptions underlying Aufmarsch II West seemed increasingly questionable. Russia and the Russian Army recovered much more quickly than expected from the ravages of war and revolution. An economic boom provided the industrial base and financial resources for large new military and naval programs, while French loans underwrote a major expansion of the rail net, which obviously would speed up Russian mobilization. Watching all this with alarm from Berlin, Moltke and the General Staff saw their margins of time and military superiority ebbing away—and this drove them to a decision that was to determine the course not only of the coming war but of twentieth-century history.

Fearful that the strategy of exhaustion would commit Germany to a long, eventually losing, war of attrition, Moltke turned again to the strategy of annihilation. Aufmarsch II West was modified to embody the strategic offensive that Schlieffen had planned for a war between Germany and France only: the Aufmarsch I West right wheel through Belgium, aiming at the destruction of the French Army. The Chief of Staff believed that Russian mobilization, improved though it was, would still take more time than that of the other powers. Here, then, was Germany’s opportunity. If the French Army could be destroyed before the Russian Army was ready to march, the encirclement of the Reich would be broken. With France prostrate, Russia could then be dealt with at leisure, and would probably opt for a compromise peace.

The German deployment plan of August 1914 was, therefore, a hybrid scheme. The balance of German forces between east and west was about equal to that of Aufmarsch II West but the revised plan of operations envisioned offensives in both theaters of war. In the east the main burden of offensive action would fall initially on the Austro-Hungarian Army, attacking into Russia from Galicia, this to relieve pressure on the small German force defending East Prussia. After France had been defeated a large part of the German Army in the western theater would go east to join the Austrians in the offensive against Russia.

Moltke also made some important tactical alterations to Schlieffen’s original plan for the offensive against France. Whereas the latter had called for maximum strength on the right and was willing to yield ground on the left, Moltke worried about a French breakthrough in Lorraine. He therefore took forces from the armies of the right wing, allotting them to the left wing. Schlieffen had planned for the right wing to pass through the southern tongue of Dutch territory, called the Maastricht Appendix. Moltke decided that it would be wiser to preserve the neutrality of the Netherlands. The result was that the front of the German right wing was somewhat constricted in the first phase of the campaign.

Thus the Schlieffen Plan as executed in August 1914 was not, as many believe to this day, one man’s brainchild, handed down intact to his successor. Though the plan was largely based on Schlieffen’s work it also reflected the thinking—and the fears—of Moltke. And though Germany's decision to seek victory through Vernichtungsstrategie ended in failure, it nevertheless determined the subsequent course of the war.

One wonders what would have happened if the Germans had gone on the defensive in the west and focused the bulk of their forces against Russia.

One benefit would have been to keep England out of the war (at least for a time).

But as you described, Germany was determined to crush France.

Love this three part essay. We’re curious about the comparison of 1914 to 1870 more than to 1815, both in armies and strategies. We’ve always understood 1870 as a dress rehearsal of sorts, with the German actors forgetting their lines, so to speak, by 1914.

If the Germans had allowed the French to exhaust themselves in offense around Lorraine--not an unreasonable expectation, given the French elan mindset and politics--surely that would have opened the Belgian flank for strong advances before the British arrived?

Going back to Napoleon and his propensity for dealing with his enemies one at a time, it seems like the Germans gave up on divide and conquer and doomed themselves to failure by taking on the world.