Part Seven: Opening Round in the East (2)

(For clarity, Austro-Hungarian formations are rendered in italics.)

The success of the German war plan—maximum effort in the West, minimum defense in the East—was dependent on the cooperation of the Austro-Hungarian ally. Prewar staff talks had reached an agreement in principle that in the event of a general European war, Austria-Hungary would launch an offensive against Russia from Galicia, thus relieving the pressure on the German Army in East Prussia. The Austrian Chief of Staff, General of Infantry Franz Graf Conrad von Hötzendorf, confirmed this arrangement to his German counterpart only months before war broke out in August 1914.

Privately, however, Conrad was a prey to uncertainty over Austria-Hungary’s best course of action. Admittedly, the strategic problem before him was a difficult one. It seemed likely that a European war would begin in the Balkans with a clash between Austria and Serbia. In Vienna, the Serbian kingdom with its designs on the Slavic provinces of the Habsburg Monarchy was seen as an existential threat, the elimination of which must be the primary Austrian war aim. If the war remained localized, well and good: Serbia could be crushed with ease. But if Russia came in everything would change. The agreement with Germany, not to mention the magnitude of the Russian threat, would require the greatest possible concentration of Austrian forces in Galicia. But though militarily Serbia was much the lesser threat, emotionally she was regarded as the main enemy by almost all Austro-Hungarian soldiers and statesmen.

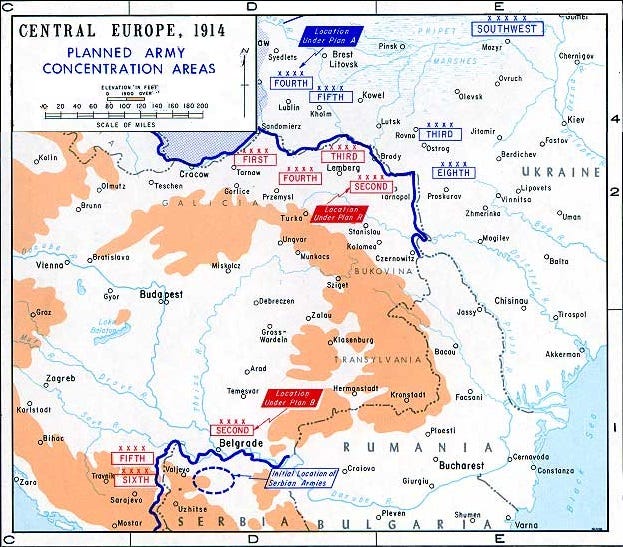

To cope with these contingencies, the Austro-Hungarian mobilization scheme (see map) divided the Army in three. A-Staffel, (thirty infantry divisions and eight cavalry divisions) would go to Galicia. Minimalgruppe Balkan, (eight infantry divisions and some cavalry) would deploy against Serbia. B-Staffel (ten infantry divisions and two cavalry divisions) was the strategic reserve, to be directed against either Serbia or Russia as the situation dictated. If the war remained localized, B-Staffel would deploy against Serbia; if it became general, B-Staffel would go to Galicia, against Russia. The railway timetables, heart of the mobilization plan, were carefully plotted to allow for an independent movement by B-Staffel. Supposedly, this arrangement ensured the flexibility necessary to cope with either contingency. But in fact, Conrad was determined to “strike Serbia down with rapid blows” in the first weeks of the war regardless of the overall situation—an intention that he concealed from his counterpart in Berlin.

In August 1914 the German High Command therefore expected the main body of the Austro-Hungarian Army—A-Staffel and B-Staffel totaling forty infantry divisions and ten cavalry divisions—to deploy well forward in Galicia, poised for an offensive. It was with consternation, therefore, that Moltke learned of Conrad’s intention to launch an immediate attack on Serbia. For this purpose, the latter had sent most of B-Staffel (now designated Second Army) to reinforce Minimalgruppe Balkan, (now designated Fifth and Sixth Armies). What was more, the three armies of A-Staffel were now to deploy well inside Galicia, there to await a Russian offensive.

Though it violated the agreement with Germany, a defensive deployment in Galicia made good military sense. Thanks to chronically exiguous prewar military budgets, the Austro-Hungarian Army was poorly armed and equipped. An especially glaring weak spot was its artillery deficit. On average, an Austro-Hungarian infantry division had only forty-two field guns and howitzers, many of them obsolescent models. Lack of money had also reduced the annual intake of conscripts to a fraction of those eligible.

The Army’s reserves of weapons, munitions and trained men were therefore scanty. Heavy losses in the first months of war, particularly of professional officers and NCOs, could never be made good, and that would cripple the Army. Offensive action in the early going would therefore be hazardous; to take up a strong defensive position in Galicia seemed much the wiser course of action. If the invading Russians were successfully repulsed, an Austrian counteroffensive might then be mounted.

Pushed and pulled by these contradictory considerations, Conrad took refuge in dithering—with unfortunate results for Austro-Hungarian mobilization.

Insistent German protests against a defensive deployment in Galicia, culminating in a direct appeal from Kaiser Wilhelm to the Emperor Franz Josef, forced the Austrian Chief of Staff to shift to an offensive deployment in Galicia after all—this after the troops of A-Staffel had already detrained, far from the frontier. To reach their new positions, they were forced to march forward on foot and horseback over distances of up to two hundred miles, exhausting men and horses in the process. Then, as the Austrian offensive against Serbia developed, Conrad sent most of Second Army to Galicia after all—thus robbing the attack on Serbia of the strength necessary to ensure success. And crowning this tale of muddle and indecision, Second Army arrived in Galicia too late to influence the course of events there.

The Russians, meanwhile, were completing their deployments against East Prussia and Galicia. Southwest Front was responsible for the Galician offensive. It controlled four armies with sixty-four infantry and cavalry divisions, a force considerably larger than the Austrians could muster and one that would be further strengthened by troops coming in from points east. The shortages of weapons and munitions that would later plague the Russian Army were yet to emerge and supplies were ample for the initial campaign. The Russian plan was, broadly, to defeat the Austrians in Galicia, then to debouch onto the Hungarian plain via the Carpathian passes, dealing a death blow to the Habsburg Monarchy.

After some preliminary cavalry skirmishes the battle for Galicia commenced on 22 August 1914 and its course would do much to determine the outcome of the Great War.

"...Conrad took refuge in dithering..."

Amazingly, he was allowed to dither for almost the entire war.