Special Study: The Austro-Hungarian Army

Of the major belligerents in 1914, the Habsburg Monarchy (Austria-Hungary) was the militarily the weakest, and its army's performance in the Great War was decidedly mediocre, though not quite so bad as is often alleged. Most of the Austro-Hungarian Army's problems were derivative of the polity it served, though it must also be noted that the Army’s senior commanders were, with occasional exceptions, none too competent. As for the troops, they could fight well enough if properly armed and led—which all too often they were not.

The Habsburg Monarchy was an ill-blended medley of nationalities, an anachronism in the age of the national state, and so was its army. This was the source of many problems, including that of language. Since regiments were organized along “national” lines, career Army officers often had to learn three, four or even six languages in addition to their native tongue. Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Chief of Staff in 1914, spoke seven languages. But gradually this traditional professional standard had been abandoned in practice if not in principle.

The officer corps had always been dominated by German Austrians and Hungarians, and by the turn of the century neither group retained the cosmopolitan outlook of earlier times. These men resented having to learn the languages of the troops they commanded—Croats, Czechs, Bosnian Muslims, Poles, Slovaks, etc.—and did their best to evade the requirement. They relied instead on the “language of service”: the few hundred German words that the troops were made to learn so that they’d understand when their officers spoke of rifles, sabers, cannons, etc. It was a situation unlikely to foster organizational cohesion, nor did it.

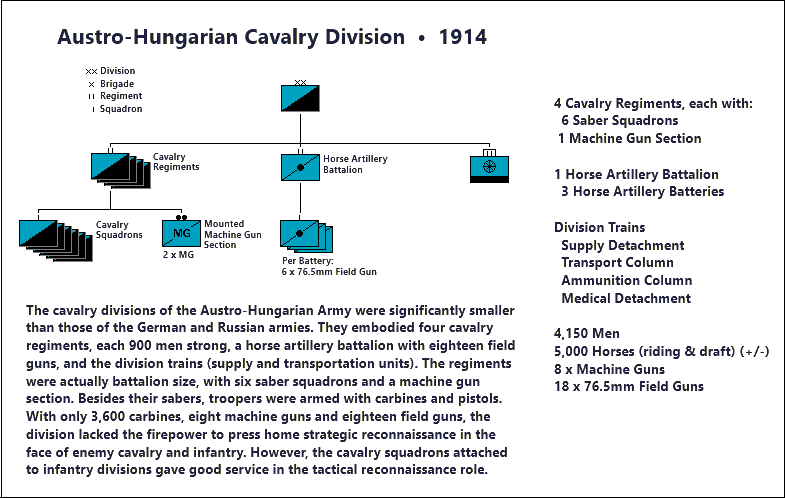

This fundamental problem of ethnicity was compounded by the Austro-Hungarian Army’s administrative deficiencies. In 1914 the Army was small (forty-eight infantry divisions, eight cavalry divisions) and poorly equipped—this despite the fact that the empire had a population of fifty million and a respectable industrial base. But since 1867 the politics of "dualism"—the unstable, uneasy relationship between Vienna and Budapest—tended to stifle military reform projects. These were proposed from time to time but the Hungarians, determined to maximize their autonomy within the Monarchy, usually were loath to give the necessary money. Moreover, both the administrative machinery of the Army and its high command were notoriously inefficient. A case in point was the management of the cavalry arm.

In 1906 the Army’s Inspector-General of Cavalry was Archduke Otto, youngest son of the heir presumptive to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Otto was a notorious wastrel who treated the position as a sinecure and did no work. A bevy of mistresses took up most of his time, and eventually took his life. When to no one’s surprise he died of syphilis, Lieutenant-General Rudolf Ritter von Brunderman was appointed in his place, with promotion to the rank of General of Cavalry.

It might be thought that Brunderman, well regarded as a commander of cavalry and celebrated as the “boy wonder” of the Army, was an improvement over the late Archduke. But if Otto had done no work, at least he’d done no harm. The same could not be said of the man who replaced him, for Brunderman was a military reactionary who sought to preserve the cavalry’s traditional role as the “arm of decision.”

At the time of Brunderman’s appointment, the Chief of Staff, General of Infantry Franz Conrad von Hötzendorff, was striving with limited success to enact yet another program of reforms. Among them was modernization of the cavalry. Building on reforms introduced in the 1870s, Conrad sought to emphasize reconnaissance and dismounted combat over mounted shock action. Cavalry regiments were to receive machine gun sections and signals detachments. Their anachronistic uniforms—dark blue tunics over red breeches, plumed shakos and brass helmets—were to be replaced by the new “pike-gray” (hechgrau) field uniform.

Brunderman set his face against these innovations. He championed horsemanship and swordsmanship instead, harking back to an era when the cavalry charged home against the enemy in close order, sabers flashing. Though the machine gun and signals units were reluctantly accepted, the cavalry regiments did not receive the training in modern warfare that they so badly needed. Nor were they compelled to give up their showy uniforms, which were only replaced in 1915.

Conrad intrigued to get rid of Brudermann, and he was finally replaced in 1912—characteristically being kicked upstairs to serve as inspector-general of the whole Army. But that left little time for his successor to correct the cavalry’s many deficiencies, and when war came in 1914, the “arm of decision” failed in most of the tasks it was given. Brunderman himself was sacked and forced into retirement after the army he commanded in Galicia was ignominiously defeated by the Russians in August 1914.

Another source of the Army’s weakness was a lack of organizational uniformity. Thanks to dualism, the Habsburg Monarchy had not one army but three. The Imperial and Royal Army (kaiserlich und königliche or k.u.k Armee) informally called the Common Army, was maintained jointly by Austria and Hungary. But in addition there were the Austrian Landwehr and the Hungarian Honvéd, which were separate organizations, recruited in the Austrian and Hungarian Crown Lands respectively. The Hungarians, jealous of their autonomy, persistently opposed increased funding for the k.u.k Armee, preferring to spend money on the Honvéd instead.

Nor did the Army possess any real reserve divisions. Nominally, the Landwher and Honvéd were supposed to constitute a reserve, but since the Common Army was so small—a mere thirty-two infantry divisions—their sixteen divisions had to be embodied in the field army upon mobilization. Peacetime military budgets were so exiguous, and conscription was applied with such laxity, that in 1914 the reserve of trained men was only sufficient to bring the existing divisions up to war strength and to replace initial losses. Adolf Hitler was but one of many Austro-Hungarian subjects who found it easy to dodge the draft.

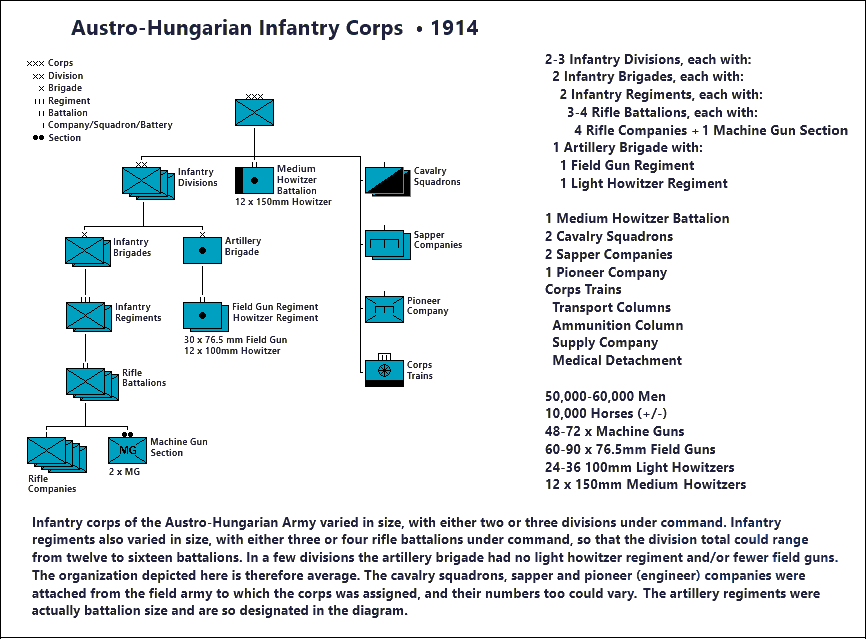

The tripartite nature of the Army also had the unfortunate effect of complicating the structure of its infantry divisions. Infantry regiments of the k.u.k Armee had four battalions, whereas those of the Landwehr and Honvéd had only three. Thanks to this, an infantry division could have as few as twelve or as many as sixteen infantry battalions, depending on the identity of its four infantry regiments. The average strength was fourteen battalions.

The divisional artillery brigade was also variable in size and quality. Usually there were two regiments, really the size of battalions, one with field guns and one with field howitzers. The former usually had five batteries, each with six guns; the latter usually had two batteries, each with six howitzers. But the number of batteries could vary, and some divisions had no howitzer regiment at all. Moreover, Austrian guns and howitzers were mostly outmoded, made of heavy bronze/steel alloy, with primitive recoil systems and roughly half the range and rate of fire of comparable German and Russian field artillery.

As for medium and heavy field artillery, at the beginning of the war the Army had very little. An infantry corps was supposed to include a medium howitzer battalion with twelve 150mm howitzers, but not all of them had one assigned. Heavy guns and howitzers suitable for employment in the field were practically nonexistent, most such weapons being permanently installed in fortresses like Przemysl in Galicia.

In 1914, therefore, the Army as a whole was ill prepared for war. Infantry training was primitive. The artillery was armed with a miscellany of obsolete weapons. Far too much faith was placed in cavalry, which as noted above was poorly trained for reconnaissance, the only useful role it still had on the modern battlefield. The result was a string of costly and humiliating defeats in the first year of the war. German assistance staved off a complete collapse, but the Army’s battle capacity had been gravely undermined and it never fully recovered. By 1917 it was operating on the Eastern Front as a mere auxiliary of the German Army, often under direct German command.

Though tales of mass surrender and desertion were exaggerated, the Army’s Slav troops grew increasingly unreliable as the war wore on. Czech soldiers especially were bitterly resentful of the disdain with which their mostly German Austrian officers treated them. Often the reliability of a given unit depended on which enemy it was fighting. Croat troops, for instance, generally fought harder against Italy, the hated “hereditary enemy,” than they did against the Russians.

Still, the Austro-Hungarian Army gave a better account of itself than might have been expected. Italy entered the war in 1915 at a moment when the Habsburg Monarchy’s military fortunes were at their nadir. Coveting Austrian Trentino, the city of Trieste and the eastern Adriatic littoral, the Italians anticipated a quick victory. But the Austro-Hungarian Army fended off no fewer than eleven Italian offensives between 1915 and 1917—this despite the fact that it was heavily outnumbered. Then in 1917, with a reinforcement of German divisions, the Austrians launched a counteroffensive that demolished the Italian Army and very nearly knocked Italy out of the war.

But this last victory came to nothing. The process of disintegration set in motion by the outbreak of war had progressed to the point that by 1917, nothing could save the Habsburg Monarchy and its Army. The former’s collapse in October 1918 was swiftly followed by the latter’s dissolution.

Don't mean to nitpick, but the Austro-Hungarians did have the output of the Skoda works (see the 8 30.5 cm Mörser M.11 howitzers which served with the Germans in 1914). It was will and finances, not capacity that hindered them.

Lesson for our military today.

As I look at the A-H military's focus on uniforms, I am reminded of trends in our military:

https://i0.wp.com/spacenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/7492233-scaled.jpg?fit=2560%2C1707&ssl=1