The story of D-Day itself is well known: General Eisenhower’s bold decision to launch the operation despite an uncertain weather forecast, the airborne assault, Bloody Omaha, the British failure to seize Caen, the 21st Panzer Division’s unsuccessful counterattack on the evening of 6 June. It was indeed “the longest day,” at the end of which the Allies were ashore. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s plan to defeat the invasion on the beaches had misfired.

But General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery’s original plan had also misfired. He had intended to capture Caen and the high ground beyond on D-Day itself, setting the stage for a breakout on the Allied left flank that would unhinge the entire German front in Normandy. To that end, the capture of Caen was to be accompanied by a rapid advance west of Caen by British and Canadian armor to “peg out” positions far inland. But Caen was not captured. This not only prevented a decisive breakthrough but restricted the size of the British/Canadian portion of the Normandy bridgehead.

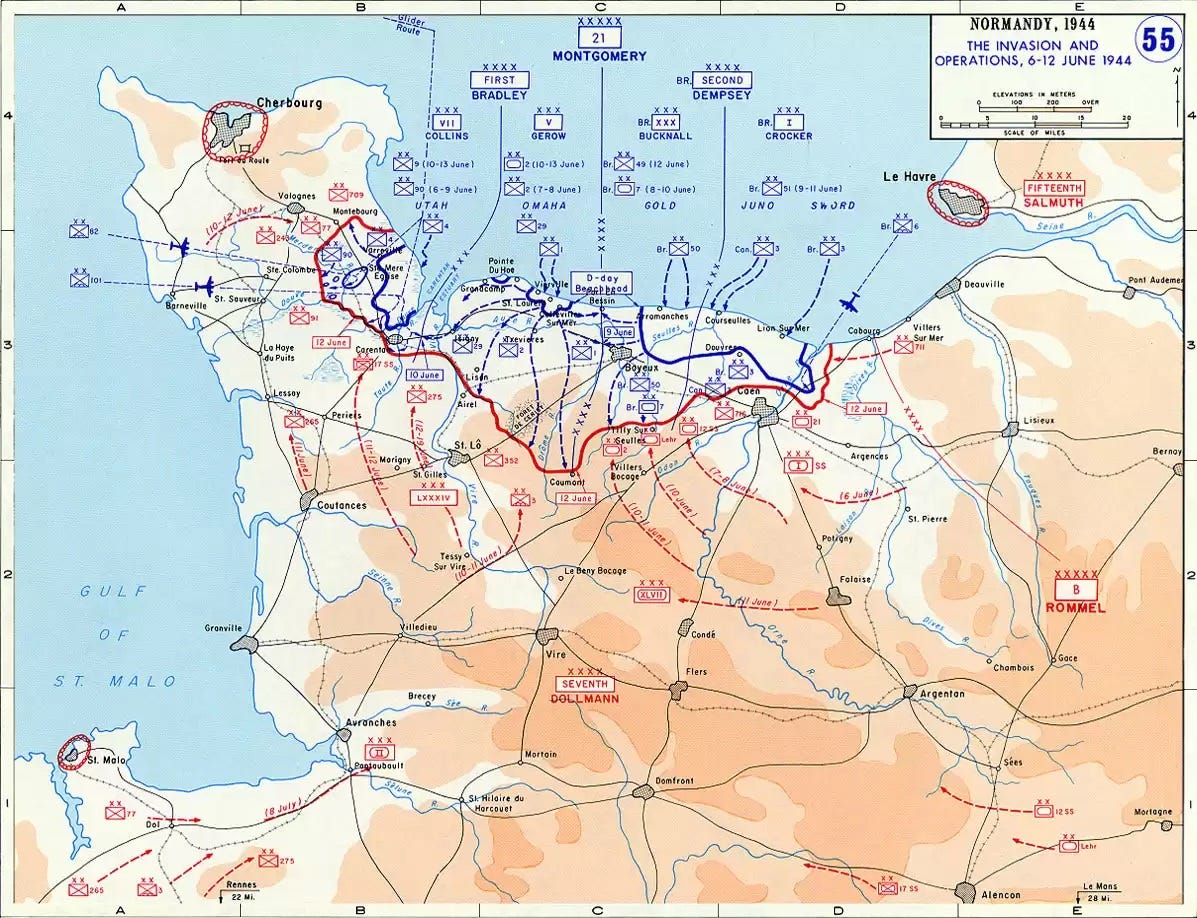

Nevertheless, the five invasion sites were soon linked together, and the consolidation of the Allied bridgehead was complete by 12 June. The front was now some sixty miles in length and twenty-five miles deep at its widest point. On the Allied right was US First Army; on the left was British Second Army. Their missions, respectively, were to capture Cherbourg, the major port at the northern extremity of the Cotentin peninsula, and to widen the British sector of the bridgehead by capturing Cean.

But in the days following the landing, Second Army continued to encounter heavy resistance on the approaches to Caen, and it seemed unlikely that the city could be taken by direct assault. Slowly but steadily, more German divisions were reaching Normandy, many of which were concentrated in the Caen sector. No less than the Allies, the Germans realized that the fall of Caen and an Allied breakthrough would spell instant disaster for them.

However, American pressure farther west had opened a gap in the German line. Montgomery decided to exploit it by pushing an armored spearhead south to the town of Villers-Bocage and the high ground beyond, from which position it could move east against Caen, outflanking the German defenses around the city. The attack was to be made by 7th Armoured Division—the famed Desert Rats—of XXX Corps. To fix German reserves in place, 51st (Highland) Infantry Division would make a subsidiary attack east of the Orne River. It was a good enough plan, but faulty execution led to a humiliating fiasco.

The Highlanders attacked on 11 June but were stopped in their tracks. Heavy fighting over the next few days cost both sides many casualties, but the British could make no progress.

Meanwhile, the advance of 7th Armoured had commenced on 10 June, and on 13 June its leading brigade reached and occupied Villers-Bocage. A little farther south was Point 213, the high ground that constituted the division’s initial objective. An armored/infantry task force was dispatched to seize and hold Point 213. But lying in wait for the British was a small detachment of the 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion commanded by Obersturmführer Michael Wittmann, a highly decorated “panzer ace” with the destruction of 117 Russian tanks to his credit.

In one of the most remarkable small-unit actions of the war, Wittmann’s handful of Tiger tanks ambushed and shot to pieces the numerically superior British task force. The Germans then launched an attack on the British in Villers-Bocage, and though this was beaten off British losses were again heavy, and the brigade commander decided to abandon the town and take up a new defensive position on higher ground to the north. But after an all-day battle on 14 June, 7th Armoured Division was compelled to withdraw to its starting positions. The Desert Rats had shot their bolt.

The British failure at Villers-Bocage ended Montgomery’s hopes of disrupting the German defense by seizing Caen. But for all his bombast and vanity, the commander of 21st Army Group was nothing if not a realist. He was quick to recognize that a change of plan was necessary, nor did he dither over the options. Second Army would continue to maintain pressure on the German front in the Caen sector. If a breakthrough could be achieved, well and good. But if not, the German reserves, including Rommel’s trump card, the panzer divisions, would be pinned around Caen, clearing the way for a breakthrough offensive by the Americans on the Allied right.

Villers-Bocage was disappointing for another reason. When he assumed command of 21st Army Group with responsibility for the initial stage of the ground campaign, Montgomery had insisted that veteran formations from his former command, Eighth Army, be transferred to Britian for OVERLORD: the 7th Armoured Division, the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, and the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division. It was believed that these battle-tested units would stiffen the untried divisions of Second Army, most of which had seen no action thus far.

But though the 50th performed well in Normandy, the 7th Armoured and the 51st did not. Containing as they did a high proportion of men who’d been serving in combat since 1940, neither division lived up to Montgomery’s expectations. The truth was that their veteran troops were tired men. They felt that they’d done their share of fighting and were bitter at being thrown into the breach again. As the saying goes, there are old soldiers, and there are bold soldiers, but there are no old bold soldiers. Those veterans of the Western Desert, Sicily, and Italy can perhaps be forgiven for agreeing with Falstaff that discretion is the better part of valor.

Villers-Bocage was an omen of troubles to come as the campaign progressed, for the British Army, an amalgam of untried and veteran units, was a force of uneven quality. Some divisions performed outstandingly well. Some improved once they gained experience. But others proved unreliable. This was particularly true of the infantry, which bore the main burden of the battle and suffered the highest casualties. That the Army was on the verge of a manpower crisis only compounded the problem. Britian’s wartime mobilization had peaked at the end of 1943 and the day was coming soon when replacements would no longer cover losses. Montgomery was well aware of these unwelcome realities, and they influenced his conduct of the battle.

The Americans too would face similar problems as the campaign in northwest Europe went on, though they never became quite as acute as those confronting the British. But problems or no, the Battle of Normandy was underway and the question before the Allied command was stark: How to win it?

Your comments about tired men resonates.

My German grandfather entered the army in 1939. Took part in the fighting in France, Russia, and Italy.

Captured in April, 1945, he was released in late 1946.

Returned home and found that the women were running the businesses well and he was not needed.

Nobody in Germany wanted to hear about a lost war.

He committed suicide in 1965.