NOTE ON CODE NAMES

OVERLORD was the code name for the general plan of campaign for the liberation of northwest Europe. NEPTUNE was the code name for the Normandy landings. D-DAY was the code name for the date on which NEPTUNE was to be executed.

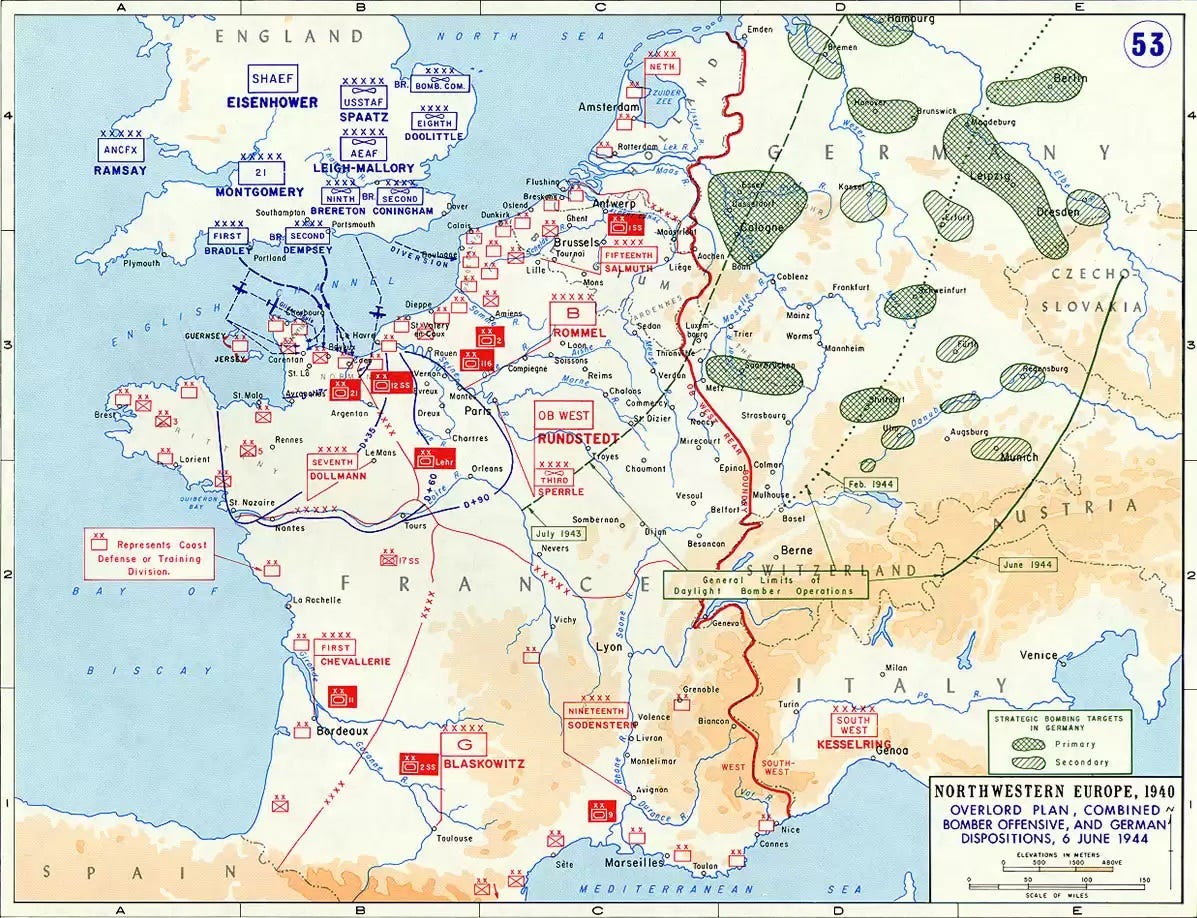

The headquarters responsible for planning and conducting Operation OVERLORD was titled Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force or SHAEF. The Supreme Commander was General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who’d been transferred from the Mediterranean theater in January 1944. His deputy commander was Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder of the Royal Air Force, and his chief of staff was Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith, US Army. SHAEF was answerable to the Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee: the senior officers of the British and American armed forces, especially General George C. Marshal, Chief of Staff, United States Army, and Britain’s General Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

SHAEF’s major subordinate commands for the initial invasion, code-named Operation NEPTUNE, were British 21st Army Group (General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery), Allied Expeditionary Air Force (Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory), and Allied Naval Expeditionary Force (Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay). Montgomery’s army group embodied British Second Army and US First Army. Leigh-Mallory’s command embodied the RAF’s Second Tactical Air Force and the USAAF’s Ninth Air Force. Ramsay’s command encompassed the naval forces that would conduct and support the D-Day landings.

Besides these forces SHAEF could call on support from other commands: the USAAF’s Eighth Air Force; the RAF’s Bomber Command, Coastal Command, and Air Defence of Great Britain (formerly Fighter Command); and the Royal Navy’s various commands including the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow.

Montgomery’s 21st Army Group was responsible for the landings and the consolidation and expansion of a bridgehead sufficiently large for a buildup of follow-on forces, culminating in a breakout offensive to roll up the German front in Normandy. At that point, SHAEF would move to France and take direct command of all Allied forces in the theater, which by then would constitute 21st Army Group (British Second Army and Canadian First Army) and US 12th Army Group (US First and Third Armies). Montgomery was to remain in command of 21st Army Group, while General Omar Bradley, the US First Army commander, would step up to the command of 12th Army Group.

Planning for the invasion of Europe began as early as 1941, before America’s entry into the war: The British Chiefs of Staff examined the possibility of a relatively small landing in the context of a sudden German collapse. But nobody took this scenario very seriously, and it was not until the Americans appeared on the scene that invasion planning gathered real momentum.

From the start it was agreed that the war could only be won by confronting and defeating the German Army in northwest Europe. The question was how soon this would be possible. The British, with their recent, none too happy, experience of fighting the German Army, tended to emphasize the risks of a too-hasty invasion. They also thought that worthwhile operations could in the meantime be conducted in North Africa and the Mediterranean area. For their part, the Americans pressed for concentration of forces and an invasion at the earliest feasible date.

The plan for an invasion in 1942 was dubbed Operation SLEDGEHAMMER. It soon became apparent, however, that action in 1942 was out of the question, and even 1943 seemed problematical, given the demands made on Allied resources by other theaters of war and the time required to complete BOLERO, the buildup of American forces in Britain.

A brutal reality check was supplied by the disastrous failure of Operation JUBILEE, a large-scale raid carried out by a joint British/Canadian force against the German-occupied port of Dieppe, France, on 19 August 1942. JUBILEE was in the nature of an experiment to see if a major port could be seized by direct amphibious assault; Dieppe was to be held for a short time only. But the result was a fiasco. The port was never reached, much less occupied, and the assault force suffered heavy casualties. Of the 5,000 Canadian troops committed to action, 3,367 were killed, wounded, or captured—a casualty rate approaching seventy percent. The RAF lost 106 aircraft; the Royal Navy lost over thirty landing craft and a destroyer. It was said later that the lessons learned at Dieppe were valuable to the invasion planners, but the price was high.

Nonetheless, planning for an invasion in 1943 went ahead under the code name ROUNDUP. Once again, the plan was premised on the collapse or great weakening of Germany. A secondary consideration was the need to take some of the pressure off the Soviet Union. Soldiers and civilians, American and British, well understood that if Russia were defeated or driven to make a separate peace, the defeat of the Axis powers would be all the more difficult and costly. Besides that, there was considerable public pressure in America and especially Britain for early action to help the USSR. This was seconded by the complaints of the Soviet government, Stalin asserting that Russia was fighting Nazi Germany alone, while the Western Allies sat on the sidelines and twiddled their thumbs.

But the dismal science of logistics and the demands of other theaters scotched the possibility of an early invasion of France. Though the Allies had agreed that the defeat of Germany must be their first priority, the Pacific theater could not simply be ignored. And in America, there was political pressure on the US government to get American troops into action against Germany as soon as possible. An invasion of French North Africa in early 1942, Operation GYMNAST, had been proposed but rejected, but now it was revived under the code name TORCH.

The North African invasion was launched on 8 November 1942, and it resulted in the total defeat and surrender of Axis forces in Tunisia. There followed the invasion of Sicily and Italy in mid-1943, which irrevocably committed the Allies to a campaign in southern Europe. And though Stalin & Co. were loath to admit it, all this did take some of the pressure off the Eastern Front.

At the TRIDENT Conference (Washington DC, May 1943) the British and Americans finally agreed that the invasion of France would take place in the spring of 1944, with Eisenhower in overall command. A British officer, Lieutenant-General Frederick E. Morgan, was appointed Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), with the responsibility for planning the operation. His first task was to select the invasion site, and the choice soon narrowed down to either the Pas de Calais or Normandy. Though the former was located at a point where the English Channel was at its narrowest, it was rejected because the terrain was unsuitable for the establishment of a sufficiently large bridgehead. It was proposed, therefore, that the landings should take place on the coast of Normandy, in the area between the base of the Cotentin Peninsula and the city of Caen.

Logistical constraints, especially the shortage of landing craft, led Morgan and his staff to settle on an initial assault by three divisions, with two more in immediate support. But when they saw this plan in December 1943, both Eisenhower and Montgomery judged it to be too small in scale. The latter argued for a five- or six-division landing to secure a bridgehead large enough to accommodate a sufficiency of follow-on forces, and this was accepted. Montgomery, who would command all ground forces during initial operations, thereupon assumed the role of chief planner—much to Morgan’s resentment at being sidelined. And though the final plan bore the stamp of Montgomery’s high professionalism and attention to detail, it is only fair to record that the work done by the COSSAC staff provided a solid foundation on which to build.

In its final form the D-Day plan involved six infantry divisions (three American, two British, one Canadian) and three airborne divisions (two American, one British). To ensure that sufficient landing craft would be available, D-Day was postponed from early May to early June.

The lessons of Dieppe and the Allied amphibious operations in the Mediterranean strongly influenced the OVERLORD plan. For instance, it was realized that the first wave of troops to hit the beaches would require the maximum possible fire support. This would be provided by the battleships, cruisers and destroyers of the Allied navies, and by amphibious tanks and specialized landing craft armed with artillery and antitank guns that would accompany the troops ashore. The mission of the airborne divisions was to seize key terrain inland and secure the flanks of the bridgehead. In the weeks before the invasion, Allied airpower was to isolate the battlefield by destroying bridges, tunnels and railroad marshaling yards. Once the invasion was underway, the air mission would be to hinder the movement of German reserves and provide close air support for the ground troops.

NEPTUNE was the largest and most complex amphibious assault every attempted, and though the Allied commanders professed confidence in the outcome of D-Day, all recognized that it would be, as their adversary Field Marshal Rommel put it, the longest day of the war for both sides.

The Russians second front demands were disingenuous.

The western allies (involuntarily) created a second front when Japan attacked them instead of Russia. This allowed Stalin to move Pacific troops to defend Moscow, which was a Godsend for the Russians.

The western allies created a third front in Africa and then Italy (my grandfather was in one of the units transferred from the Stalingrad Front to southern Italy - much to his relief).

The western allies created a fourth front with their air campaigns. Perhaps 20,000 dual purpose AA guns defended the Reich - imagine what they would have done to Russian tank formations.

Additionally, Germany kept its best fighters in the west to counter the advanced western aircraft. Imagine how many Hartmann's would have been created if those fighters formations had been on the eastern front.

Consider what the Russians might have faced if German industrial production had not been throttled by western air power.

So Overlord was really the fifth front helping the Russians.

Plus, let's not forget Lend Lease. The Russians were hugely aided by the supplies received - just look at pictures of the Russian armies in 1945.

Perhaps 25% of German combat power fought in the west; but counter factually, consider if those tank formations and air power had been available at Kursk.