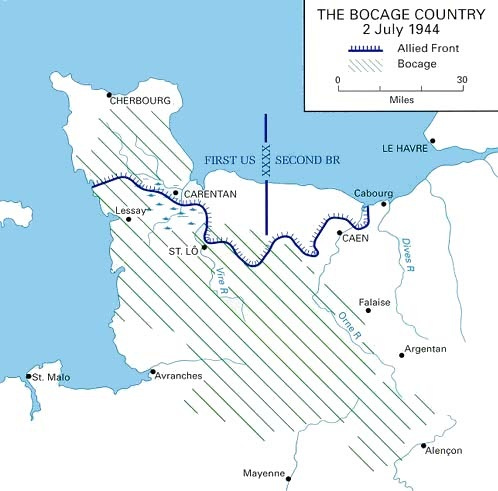

After the clearance of the Cotentin Peninsula, the capture of Cherbourg, and the termination of Operation EPSOM, the Allied front in Normandy ran from the vicinity of Caen in the east to Port-Bail-su-Mer on the English Channel in the west. The British sector of the front ran from Caen to the town of Cahagnes, where Second Army’s right flank linked up with US First Army’s left flank. The two armies constituted 21st Army Group, commanded by General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery. The Allies faced Seventh Army, which was responsible for the entirety of the German front until 28 June, when Panzer Group West (General of Panzer Troops Heinrich Eberbach) assumed command of the four corps of the right wing. This left Seventh Army with two corps, facing the Americans. After the death, possibly by suicide, of its previous commander, Colonel-General Friedrich Dollmann, command of Seventh Army had devolved upon SS-Obergruppenführer Paul Hasser, previously the commander of II SS Panzer Corps.

The disappointing outcome of EPSOM and the subsequent criticism that came his way had no effect on Montgomery’s basic strategy. He remained committed to a policy of unrelenting pressure by Second Army on the German front around Caen. If this should result in a breakthrough, well and good. But if not, it would draw enemy reserves to the Caen sector like a magnet—the Germans being well aware that an Allied breakthrough there would spell instant disaster for them. And meanwhile, First Army would push south, expanding its sector of the bridgehead in preparation for a major offensive. As broadly conceived, Operation COBRA, as it came to be codenamed, would first rupture the German front west of Saint-Lô, then drive south to Avranches, setting the stage for further advances into Brittany and due east, rolling up the entirety of the German front in northern France.

But Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley’s US First Army, which would conduct COBRA, faced no easy task. Though Cherbourg had been captured, the Germans had managed to wreck its port facilities. That meant that supplies and reinforcements would have to come in over the beaches, a cumbersome and time-consuming procedure necessitating the transfer of personnel and material from cargo ships to landing craft for delivery ashore.

Nor was the ground favorable for large-scale offensive operations. From First Army’s junction with British Second Army to the vicinity of Saint-Lô, and again from a point south of Saint Sauveur-le Vicomte to the Channel coast, its front traversed the bocage. In between these two sectors was a low-lying area of bogs and marsh, the Carentan plain.

The Field of Battle

The bocage is the characteristic terrain of Normandy. It consists of dense hedgerows: earthen mounds topped by a tangle of hawthorne, brambles, vines and trees, one to three feet wide and three to fifteen feet high, enclosing plots of pasture and orchid. Besides delineating property boundaries, the hedgerows protect crops and livestock from ocean winds and provide the inhabitants with a ready source of firewood. The plots are mostly small, some two hundred by four hundred yards, and variable in shape. The terrain thus presents the picture of an irregular checkerboard of enclosed fields, conforming to no logical pattern.

Each enclosed plot has one entrance for people, livestock, and vehicles. Since many plots are not adjacent to a main road, the bocage is crisscrossed by numerous trails between the hedgerows, essentially sunken lanes. In places where the hedgerows are high, the vegetation grows together overhead, shutting out direct sunlight.

Thus the bocage is challenging terrain for an attacker. Fields of observation and fire are limited, reducing the effectiveness of armor, artillery and close air support. But the bocage is ideal terrain for a defense in depth, as the Germans were quick to perceive. A group of enclosed plots constitutes a natural defensive position, well suited to the employment of machine guns, mortars and infantry antitank weapons, categories of armament that the Germans possessed in plenty. A network of such positions, echeloned in depth, cannot not be broken through by some bold armored thrust. For the Americans, the battle of the bocage would be a vicious close-quarters fight, grinding through the German defenses, strongpoint by strongpoint.

The Carentan plain is equally daunting for an attacker. West of the town are five large marshes, the prairies marescageuses, lying at or below sea level. These and many smaller bogs and swamps occupy more than half the area of the plain. In summer the ground is waterlogged and treacherous, impassable for vehicles except along the few paved causeways that link the area’s settlements. The other segment of the plain is hedgerowed agricultural lowland, divided into plots even smaller than those of the bocage. Though the ground there is somewhat firmer, fields of observation and fire are extremely limited, with few avenues of approach.

The Defenders

Though the battle of the bridgehead and the fall of Cherbourg cost Seventh Army many casualties and severe material losses, the Germans had by no means been defeated. Senior commanders, indeed, had no illusions about the battle’s ultimate outcome, but among the troops morale remained, if not high, then unbroken. This bore testament to the excellence of their leaders at the unit level. As the historian Max Hastings has noted, though German command at the corps level and above was usually not much better than that of the British and American armies—and occasionally worse—at the division level and below it was superb. This could not of course compensate for the enemy’s superior firepower and airpower, but it made the Allies’ task that much more difficult.

The Seventh Army sector was held by LXXXIV Corps from the Channel coast to a point northwest of Saint-Lô, and by II Parachute Corps from there to the junction with Panzer Group West just west of Caumont. LXXXIV Corps had a panzer grenadier division, an infantry division, an independent parachute regiment and several battlegroups formed from the remnants of five infantry divisions. II Parachute Corps had two parachute divisions and one battlegroup. German parachute units belonged to the Luftwaffe, not the Army, and by 1944 they were regarded as elite infantry, since only a minority of their troops were qualified parachutists.

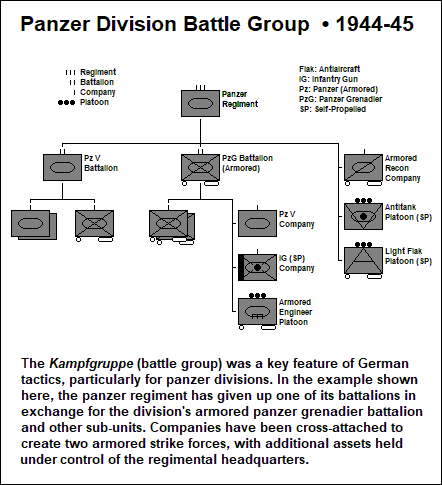

Their tactical doctrine, of which the battlegroup was a key component, enabled the Germans to maximize the defensive potential of the bocage and the marshes. Though on paper the German Army’s unit organizations looked much the same as that of the US and British armies, organization for combat was highly flexible. Battlegroups (Kampfgruppen) were formed by cross-attaching sub-units. Illustrated below is a Kampfgruppe built around the armored regiment of a panzer division. One of its two tank battalions has been swapped out for an armored infantry battalion. At the company level, one tank company of the armored battalion has been swapped out for an armored infantry company, creating two task forces, one tank heavy and one infantry heavy. The Kampfgruppe’s organization is completed by attached reconnaissance, antitank, flak (antiaircraft) and engineer units.

This procedure could be carried out at any level of command, for instance by attaching a platoon of self-propelled tank destroyers to a rifle company. The precise composition of a Kampfgruppe was dependent on its mission, the terrain, and available resources. In the bocage, defensive positions were typically held in company strength, with tanks and tank destroyers in concealed positions, weapons sited to dominate all avenues of approach, and preplanned mortar and artillery concentrations on call.

The type of Kampfgruppe described above represented standard practice in German divisions of all types. But there was another type which played a major role in the Normandy fighting: the alarm unit, raised on an emergency basis from available resources. The divisional battlegroups included in the Seventh Army order of battle were of this type. They were formed principally from the remnants of fought-out divisions, augmented with whatever other units lay ready to hand. Supply troops, artillerymen who’d lost their guns, combat engineers, stragglers, were formed into provisional infantry companies. Badly depleted units were consolidated. Naval and Luftwaffe units were drafted in. The German Army’s ability rapidly to form such Kampfgruppen and make them combat effective bore testament to the quality of its training and small unit leadership.

The emergency Kampfgruppe was usually of regimental or battalion strength, but once again the procedure could be carried out at any level of command. Time and again, small alarm units thrown hurriedly together in response to a crisis brought a promising Allied advance to a premature halt. When no orders from higher headquarters were available, junior officers and NCOs took the initiative themselves, commandeering troops in the area and leading them into a counterattack.

Between the difficult terrain and a tenacious defense, First Army’s breakout offensive would be no walkover. It was evident to every American soldier, from General Bradley on down, that the Germans intended to stand and fight—and more, that they’d conduct an active defense, counterattacking whenever possible to erase or limit American gains.

The conduct of the German defense thus reflected the strategy laid down by Hitler: to play for time while resources were assembled to mount a counteroffensive in full force, destroying the Allied armies in their bridgehead. That the German command in the West regarded this as a forlorn hope mattered not at all: The will of the Führer would now determine the course and outcome of the Battle of Normandy.