After British Second Army’s failure to capture the city of Caen on D-Day and the setback at Villars-Bocage (10-14 June), Allied ground commander General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery was forced to reassess his strategy. Having ruled out a direct assault on Caen, which he thought would be too costly in men and material, Montgomery considered the option of outflanking the city to the east by launching an offensive out of the Orne River bridgehead, which was held by British 6th Airborne Division. Operation DREADNOUGHT, as it was dubbed, would be entrusted to British VIII Corps, which was due to arrive in Normandy soon.

But a severe storm that blew up in the English Channel on 19 June and lasted three days caused considerable havoc, among other things delaying the arrival of VIII Corps. DREADNOUGHT, originally scheduled for 19 June, had to be put off for several days. Then the corps commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Richard O’Connor, voiced objections to the plan, pointing out that due to the small size of the Orne bridgehead it would be impossible fully to deploy his three divisions for the offensive.

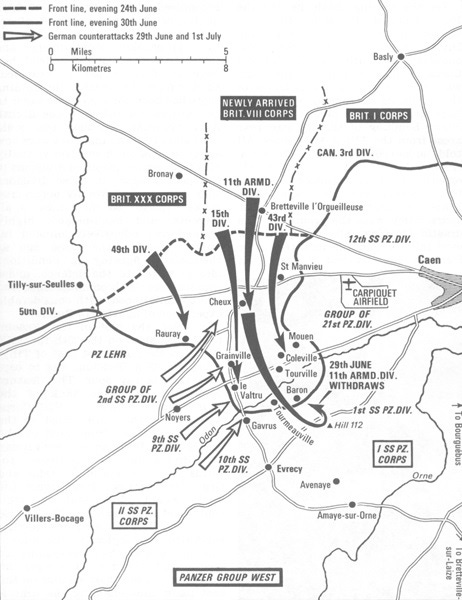

O’Connor’s objection was cogent, and so DREADNOUGHT was cancelled. Instead, Montgomery decided to insert VIII Corps between XXX Corps and I Corps, in the sector of 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. The revised plan, dubbed Operation EPSOM, projected an offensive to outflank and isolate Caen from the west, somewhat in the manner of the Villars-Bocage operation but larger in scale. EPSOM would be preceded by a preliminary operation, dubbed MARTLET. The 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division and the 8th Armoured Brigade (XXX Corps) would seize ground to protect the vulnerable right flank of VIII Corps, while 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (I Corps) would attack out of the Orne bridgehead with the objective of fixing 21st Panzer Division in place, preventing its deployment against EPSOM.

For EPSOM, the initial attack would be made by 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division of VIII Corps and the attached 31st Tank Brigade. To its left, the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division would initially remain on the start line to provide a “firm base.” The 11th Armoured Division with the attached 4th Armoured Brigade would be held in corps reserve, to be committed as the situation dictated. The attack would unfold in four phases: (1) a five-mile advance by the Scots, later dubbed the “Scottish Corridor,” to secure bridgeheads across the Odon River; (2) a drive by 11th Armoured, crossing the Odon and seizing the high ground farther to the southeast; (3) an advance to the Orne River, bypassing Caen; and (4) if possible, a drive across the Orne toward the Caen-Falaise Plain.

“We have now reached the showdown stage,” Montgomery told his commanders during a pre-attack conference on 23 June. He admitted, however, that the bad weather and the need to modify the plan had set back his timetable, granting the Germans precious time to strengthen their defenses. Nonetheless, the Allied commander was going for the big solution: a full-scale offensive by Second Army with the aim of unhinging the right flank of the German front, opening the way for exploitation toward Paris and the German frontier.

On the other side of the hill, Hitler had ordered Field Marshal Erwin Rommel to launch a counterattack against Second Army, and the Army Group B commander was in the process of assembling an armored strike force for that purpose. Major reinforcements were due to arrive from the Eastern Front: II SS Panzer Corps with two divisions, 9th and 10th SS Panzer. But after a rapid move by rail to western Germany, its arrival at the Normandy front was greatly delayed. As usual, Allied air supremacy made daylight movement by rail or road virtually impossible. Thus some of the time that Montgomery had lost due to bad weather was made up for him by Allied airpower.

For EPSOM, VIII Corps was reinforced by the 4th Armoured Brigade, the 31st Tank Brigade, and much of the artillery of I Corps and XXX Corps, for a total of 60,000 men and some 600 guns and howitzers, plus the guns of three cruisers of the Royal Navy. The corps commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Richard O’Connor, was highly regarded by Montgomery. He had commanded the Western Desert Force in North Africa in 1940-41, scoring an impressive victory over the Italians—an Axis fiasco that led Hitler to send a small mechanized corps to Libya under the command of Erwin Rommel. But then O’Conner had the misfortune to be taken prisoner by the enemy, and he spent the next two and a half years in Italian captivity. Regaining his freedom after Italy’s capitulation, he returned to Britain and was given command of VIII Corps.

O’Conner’s corps embodied some of the crack formations in Second Army. The 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division was generally regarded as the best British infantry division in Normandy. The 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division also enjoyed a good reputation. The 11th Armoured Division whose commander, Major-General Philip “Pips” Roberts, was an experienced tank man, was the best of the British armoured divisions. To use a cricket metaphor of which Montgomery was fond, he was putting in his “best batsmen.”

From northeast to southwest, the German defenders in the Caen sector were 21st Panzer Division, covering the direct approaches to the city; a battle group of 12th SS Panzer Division; Panzer Lehr Division; and a detached battle group of 12th SS Panzer Division. Also present were battle groups of several infantry divisions. The 1st SS Panzer Division was still on the move from Paris to Normandy, and 2nd SS Panzer Division was in the line around Saint-Lô, facing the Americans. The two divisions of II SS Panzer Corps were just arriving. The German troops were posted in well-prepared defensive positions. The German commander on the spot was SS-Obergruppenführer Josef “Sepp” Detrich of I SS Panzer Corps, a founding member of the Waffen-SS and one of Hitler’s oldest cronies.

In the sector of the British attack, the Odon River flows northeast to the southern suburbs of Caen, where it joins the Orne River. The terrain is mostly open farmland until the northern bank of the Odon is reached, where terrain combining a cluster of villages with the bocage—the hedgerow country of Normandy—favors the defense. On the south side of the river the ground rises to a height labeled on the map as Hill 112, just south of the villages of Gavrus and Baron. This was the first important EPSOM objective, the possession of which would open the way for a subsequent drive toward Falaise.

The British offensive commenced with Operation MARTLET on 25 June, the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division and the 8th Armoured Brigade of XXX Corps attacking with heavy air support toward the village of Rauray. They opened a three-mile gap in the German line, but despite suffering heavy casualties Panzer Lehr managed to retain control of the village. On the opposite flank, 51st (Highland) Infantry Division made scant progress against 21st Panzer Division, which later was able to detach a battle group to oppose EPSOM

EPSOM itself commenced the following day to the accompaniment of a powerful artillery bombardment. Despite rainy weather that limited air support, the Scots made good progress at first. But when they neared the Odon, the attack bogged down. The cluster of villages there had been developed into fortified strongpoints by the Germans, and a vicious close-quarters fight ensued. Two German counterattacks were repulsed with the help of prompt and powerful support by the artillery, but the Scots’ advance came to a halt a mile from the north bank of the Odon.

O’Connor thereupon decided to commit the 11th Armoured Division against the strongpoints south of the village of Cheux, which were held by the 12th SS. Little progress was made, however, the Germans extracting a heavy price for every foot of ground they gave. Thanks to bad weather and the staunch German defense, the first day of EPSOM closed on a note of frustration, with VIII Crops stalled a mile north of the Odon.

Though the Germans had managed to limit British gains, the size and power of the attack alarmed Sepp Detrich. He appealed to his higher headquarters, Seventh Army, for reinforcements. In particular, he wanted the newly arrived II SS Panzer Corps for a counterattack against the right flank of the British penetration. But General Dollman, the Seventh Army commander, and Rommel were against this: They wanted the arriving armored formations to be concentrated for the major counteroffensive ordered by the Führer. However, Rommel did agree to provide battle groups from 1st and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions to reinforce the defense in the Caen sector.

On June 27, VIII Corps repulsed a German counterattack and subsequently the Scots, joined now by the 43rd (Wessex), were able to push on to the Odon. They captured a bridge, enabling 11th Armoured to get across the river and establish a bridgehead just short of Hill 112. But the Second Army commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Dempsy, was worried about the possibility of another German counterattack. He therefore ordered the advance to be suspended until the Odon bridgehead could be consolidated and expanded.

A powerful German counterattack was indeed to come. Dollman at Seventh Army had been losing his nerve for days and the news that the British had a bridgehead over the Odon, coming so soon after the fall of Cherbourg, sent him into a panic. On 28 June he ordered SS-Obergruppenführer Paul Hasser, commanding II SS Panzer Corps, to launch an immediate counterattack. Hausser, whose troops had just arrived, requested a delay to get the attack properly organized. Dollman refused. So the attack went in on 29 June, to be decisively repulsed by the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division. That same day, Dollman died, whether of a heart attack or by suicide has never been definitively established. Hausser was named to replace him.

Also on 29 June, 11th Armoured captured Hill 112: the vital terrain feature on which the success of EPSOM depended. But now the fog of war and what Clausewitz had called “frictions” intervened. At Second Army, Dempsy gathered the impression that the II SS Panzer Corps counterattack was merely a feint, and that the main counterattack was yet to come. Nor was he given any inkling that the Germans had received a drubbing at the hands of the Scots. And so he ordered O’Connor to abandon Hill 112, pull 11th Armoured back across the Odon, and position it in readiness to deal with the expected German counterattack.

Dempsy’s understandable but mistaken decision set the seal of failure on EPSOM. When the situation was clarified and the British attempted to retake Hill 112 on 30 June, they found the Germans well dug in. The fighting was intense, and casualties mounted alarmingly. A rash commander might have prolonged the battle. But whatever his faults, Bernard Montgomery was a realist. Though bitterly disappointed, he saw that EPSOM had misfired, and late in the day on 30 June he ordered the offensive to be suspended.

Coming as it did in the wake of the Villars-Bocage fiasco, the failure of EPSOM supplied Montgomery’s numerous critics, British and American, with plenty of ammunition—and their ire was compounded by the Allied ground commander’s lack of candor. Montgomery had calculated all along that offensive action in the British sector of the Normandy front would pin major German forces in place. If a breakthrough could be achieved, well and good. If not, however, the Germans would be prevented from organizing a large-scale counteroffensive, and a breakthrough in the American sector would be made easier. But ego and hubris prevented Britain’s best general from taking anyone into his confidence. Everything was always claimed to be going according to plan.

There was another factor. British casualties during EPSOM had been alarmingly high. As ever, it was the infantry that suffered most, the gallant 15th (Scottish) losing nearly fifty percent of its infantry strength. In all, VIII Corps suffered over 7,000 casualties (killed, wounded, and missing in action). For their part, the Germans suffered some 3,000 casualties. Montgomery was aware that in view of the manpower crisis confronting the British Army, such losses could no longer be fully replaced. Already he was facing the necessity of disbanding one of his infantry divisions to keep the rest up to strength. This no doubt was a factor in his decision to cut his losses on the Odon.

Tactically and operationally, the Battle of the Odon was a German victory, in that they were able to prevent a British breakthrough, and that the ground gained by the British was of scant tactical significance. Strategically, however, EPSOM further eroded the German position. Rommel’s planned counteroffensive would never take place, since the requisite forces were now committed to the defense of Caen. After EPSOM, all the Germans could do was play for time—with the odds titling more steeply against them with every day that passed.

Interesting column on battles during the Normandy campaign that are not discussed much. Having just watched "A Bridge Too Far" for the second time after many years, I'd been interested in your analysis and comments on Operation Market Garden, another ambitious failure by Field Marshall Montgomery.

General comment about Allied logistical skills.

Overlord showed the Western Allies to have the best logistical capability of any military in memory.

The pier at Gaza showed that the US military has lost that institutional memory.