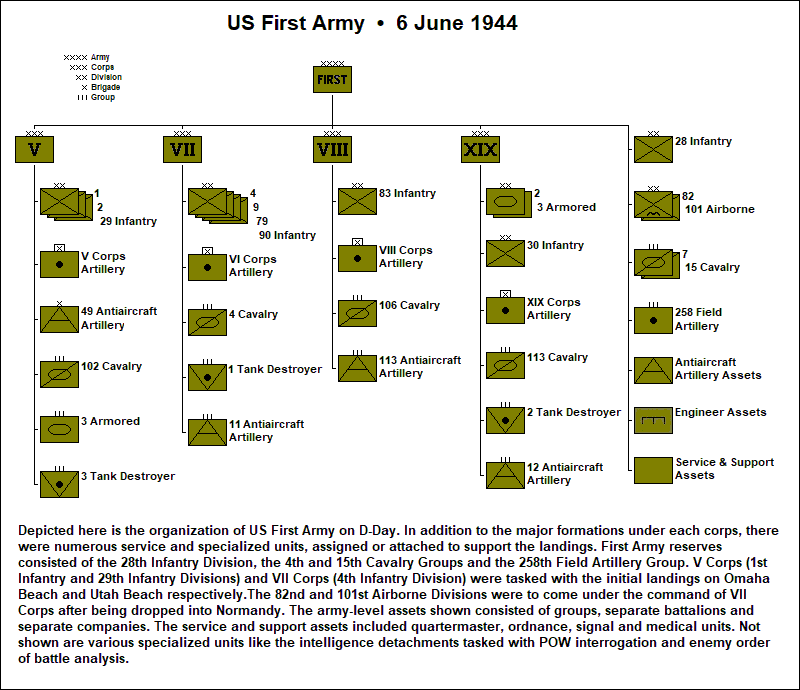

On D-Day, 6 June 1944, eight Allied divisions were committed to battle: three American infantry divisions, two British infantry divisions, two American airborne divisions and one British airborne division. The American contingent was under US First Army; the British/Canadian contingent was under British Second Army.

From west to east, the landings were to be conducted as follows. US 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions under US V Corps were to assault Omaha Beach; the US 4th Infantry Division under US VII Corps was to assault Utah Beach. British 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division was to assault Gold Beach, Canadian 3rd Infantry Division was to assault Juno Beach, and British 3rd (London) Infantry Division was to assault Sword Beach. US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were to land inland behind Utah Beach; British 6th Airborne Division was to land inland behind Sword Beach.

Attached to all five infantry divisions for the assault were numerous support units: artillery, amphibious tank, specialized armor, commandos and rangers, naval shore fire control parties, combat and construction engineers, beach groups (to organize the beachhead, manage traffic, evacuate wounded, etc.), military police and more. The divisions themselves, however, had a standard organization. Differences between the US and British organizations were found mostly in the divisional sub-units.

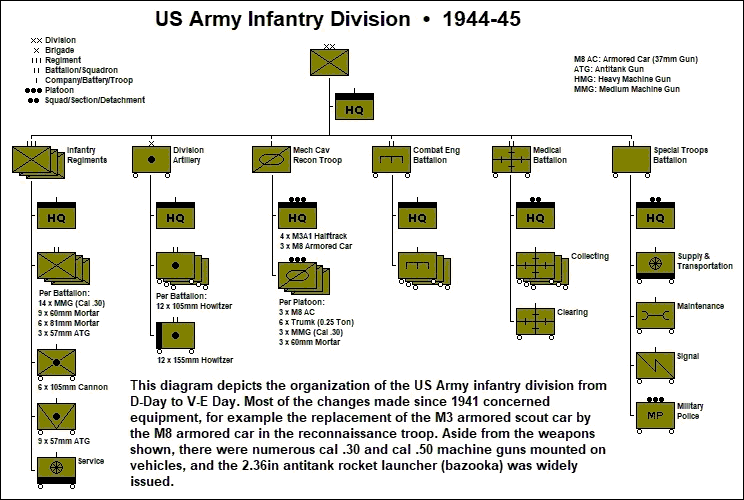

The US infantry division was a “triangular” unit: three infantry regiments, each regiment with three battalions, each battalion with three rifle companies and a heavy weapons company. Each regiment also had an infantry cannon company and an antitank company. The division artillery (DIVARTY) command was a brigade-echelon headquarters controlling four field artillery battalions, three with 105mm howitzers and one with 155mm howitzers. The division’s organization was completed by a mechanized cavalry reconnaissance troop, a combat engineer battalion, a medical battalion, and a special troops battalion (division headquarters company plus supply, transportation, maintenance, signal, and military police assets).

The British infantry division was also triangular, with three infantry brigades, each brigade with three battalions, each battalion with four rifle companies and a support (heavy weapons) company. The division artillery command (Commander, Royal Artillery or CRA) controlled three field artillery battalions, all with 25-pdr howitzers, an antitank battalion, and a light antiaircraft battalion. The division’s organization was completed by an armored reconnaissance battalion, a machine gun battalion (medium MGs and 4.2in mortars), a combat engineer battalion, and an array of service and support units similar to those of the US infantry division. The US and British airborne divisions were also triangular, with three regiments or brigades. They were, however, more lightly armed, for instance with 75mm pack howitzers in place of 105mm or 25-pdr howitzers.

US and British armored divisions were also quite similar. The former had two combat commands: tactical headquarters to which divisional sub-units could be attached as required to create task forces. (A third combat command was added later). The sub-units consisted of three armored battalions (M4 medium and M5 light tanks), three armored infantry battalions (M3 armored halftracks), and three armored self-propelled field artillery battalions (105mm howitzers). The division’s organization was completed by an armored cavalry reconnaissance squadron with armored cars and light tanks, an armored combat engineer battalion, an armored signal battalion, and the division trains (supply, transportation, maintenance and medical assets). This organization was introduced in 1943 and was called the light configuration. However, the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions, which had already been sent overseas, were not converted, retaining the previous heavy configuration.

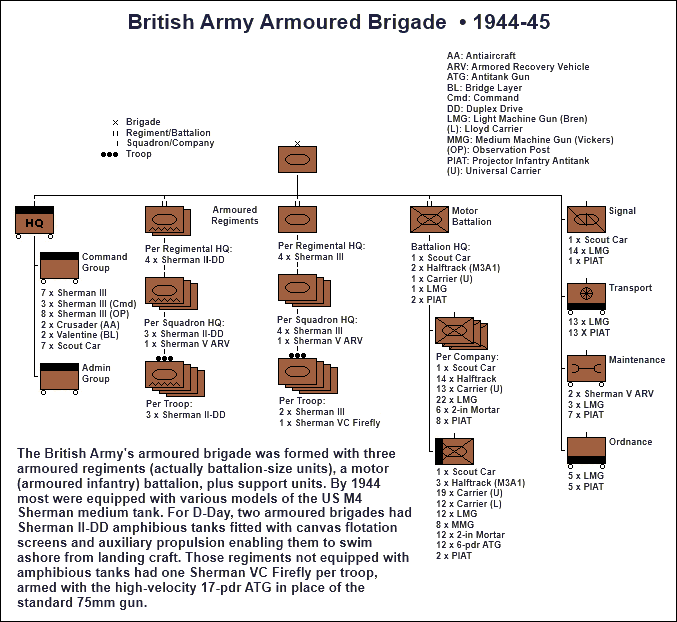

The British armoured division had about the same number and type of sub-units, but instead of combat commands these were under an armoured brigade and an infantry brigade. The former had three armoured regiments (actually the size of a battalion) with US M4 Sherman and British Cromwell medium tanks, and a motor (armoured infantry) battalion. The infantry brigade was identical to those of the infantry divisions. Divisional artillery consisted of one towed and one armoured self-propelled field artillery battalion, both with 25-pdr howitzers, an antitank battalion, and an antiaircraft battalion (both armoured self-propelled).

The Allied order of battle also included a large number of non-divisional combat units, either held under corps or army control, or attached to the D-Day assault divisions. Attached to the US 1st Infantry Division, for instance, were a regimental combat team from the 29th Infantry Division, the Provisional Ranger Group (two battalions), a detachment of the 3rd Armored Group (three battalions), two armored self-propelled field artillery battalions, four combat engineer battalions, an antiaircraft automatic weapons battalion, and an assortment of service units. The British 3rd Infantry Division had an armoured brigade, a commando brigade, and an array of specialized armour and engineer units under command.

All assault divisions, infantry and airborne, were task organized. The US airborne divisions, for example, were split into three echelons: Force A (parachute landing), Force B (glider landing), and Force C (seaborne landing).

Following D-Day and the consolidation of a bridgehead, additional Allied forces would land in Normandy. US First Army’s strength would rise to two armored divisions, ten infantry divisions, and two airborne divisions. British Second Army’s strength would rise to three armoured divisions, nine infantry divisions and one airborne division. Ultimately, sufficient forces would arrive to permit the activation of US Third Army under 12th Army Group and of Canadian First Army under 21st Army Group. Later still, US Ninth and Fifteenth Armies would join 12th Army Group, which thus became the largest combat force ever fielded by the United States Army.

A notable feature of the evolving Allied order of battle for OVERLORD was the growing disparity caused by the growth of the US contribution and the stagnation of the British contribution. Britain’s wartime mobilization commenced in 1939 and reached its maximum potential by late 1943. From that point on, British military power was a wasting asset—as the country’s civilian and military leaders were well aware.

The many critics of Montgomery’s allegedly excessive caution during the Battle of Normandy failed to appreciate that the British Army’s ability to replace manpower losses was nearing the limit. But the commander of 21st Army Group was acutely aware of the problem, and of the need to “do the business,” as he put it, with the fewest possible casualties. This factor was one among several that governed his conduct of the battle.

British anxieties concerning the manpower problem proved to be well founded. Even before the Battle of Normandy ended, Montgomery was compelled to dissolve one infantry division, using its personnel as replacements for the Second Army's remaining divisions. Inevitably, this stagnation of its military capacity diminished Britain’s influence in the upper echelons of the Grand Alliance. Ironically, the Americans too found themselves faced with the same problem later, but in Normandy they were not yet troubled by it.

Such was the composition of the Allied Expeditionary Force whose first echelon would be committed to action on D-Day, 6 June 1944.

The first chart on the US First Army shows the 3rd Armored Division in two places, under V Corps and under XIX Corps. Is that correct?

I've read elsewhere that to avoid confusion during transport, divisions were landed in the same order as they had been stationed in England, so Americans landed in the western part and British in the eastern part of Normandy. The western part was hedgerow country, unsuitable for tanks although the Americans had the stronger armored component and stronger growth potential, as you noted.