In a recent back-and-forth on the Gaza conflict with an “anti-Zionist” denizen of Substack, I was huffily informed that it is “never acceptable” for “innocent civilians” to be targeted in war. Now this represented an attempt to smuggle in a claim not backed by the evidence: that Israel is deliberately targeting civilians in Gaza and, one supposes, committing “genocide.” But that’s not my subject today.

There are several problems with my interlocuter’s claim. One is that the whole history of warfare refutes it. From ancient times to the present moment, it has always been considered acceptable to target civilian populations. The Peloponnesian War is usually symbolized by the clash of hoplite armies on some small patch of ground. But in fact, battles pitting the heavy-armed infantry of the Greek city-states against one another were comparatively rare. In his history of that epic conflict, A War Like No Other, Victor Davis Hanson notes that surprise night attacks, sieges, raids, devastation of productive land, the sacking and destruction of cities, filled the intervals between set-piece battles in the Greek tradition. Civilians in large numbers died in the course of this warfare: massacre, famine and plague ravaged Greece.

Many centuries later, the armies of the Union would fight much the same kind of war: Sherman in Georgia, Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. To read Bruce Catton’s account of Sheridan’s Valley campaign in A Stillness at Appomattox, the final volume of his Army of the Potomac Trilogy, is a sobering experience.

In between there were numerous other wars. In Henry V, Shakespeare has Chorus announce:

O, for a muse of fire that would ascend The brightest heaven of invention! A kingdom for a stage, princes to act, And monarchs to behold the swelling scene! Then should the warlike Harry, like himself, Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels, Leashed in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire Crouch for employment.

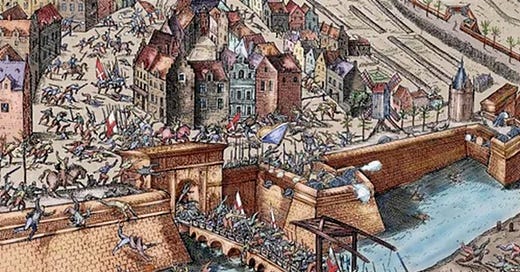

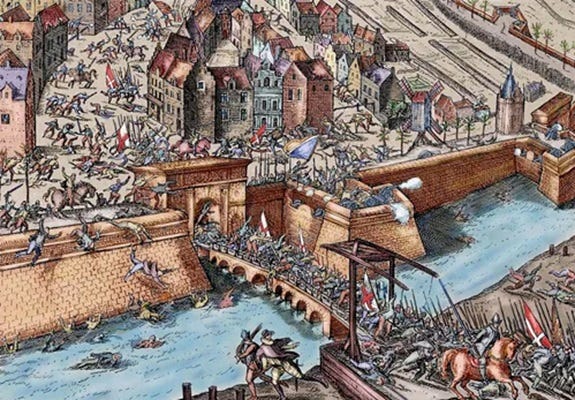

Henry’s invasion of France was the violent climax of the Hundred Years War in which, as one historian put it: “For over a century one Western nation systematically plundered another”—not sparing the civilian population. Some time later came the terrible Thirty Years War, in which as many as eight million soldiers and civilians lost their lives. In the Germanies, where much of the fighting took place, the populations of some areas fell by fifty percent.

In the eighteenth-century Age of Absolutism, wars were, indeed, less broadly destructive. This, however, was not primarily due to any softening of manners but to the character of the absolutist states and their armies. For instance, soldiers could not be trusted to live off the land. Composed as the armies were of mercenaries and the dregs of society, desertion was a chronic problem: Men sent out to forage could not be counted upon to return to the ranks. So in the train of the armies were ponderous supply columns, fed from a chain of “magazines.” Civilians had much less to fear from armies of this kind.

But these armies of the kings were a transitory phenomenon. The French Revolution heralded a revolution in the fundamental character of war. No longer were they affairs of state focused on some limited objective or, as in the case of Britain, on distant colonial gains. War now became an affair of whole peoples, of the nations in arms. And with the coming of the Industrial Revolution, the destructive potential of warfare jumped by orders of magnitude.

Attempts were made to limit the destruction that wars might cause. Hitherto, the laws of war had been customary rather than formal: for instance, the “practicable breach” in a siege. This custom laid down that when fortifications had been so reduced as to make an assault possible, the defending garrison might opt to capitulate with the “honors of war,” often being permitted to march off under arms. But if the defenders refused to capitulate, they would receive no quarter. In its way this was an eminently practical custom, designed to avoid useless bloodshed.

In the early twentieth century, the European nations sought to codify the laws of war. But while it would be going too far to say that these efforts were futile, the great wars of the twentieth century demonstrated their limitations.

During the World War I, the most striking example of warfare against “innocent civilians” was the Allied naval blockade of Germany. Estimates are that as many as 600,000 Germans died due to malnutrition and disease related to the blockade. It was a silent, slow-acting weapon, unlike the Allied strategic air offensive of World War II, which killed more than 400,000 German civilians.

Altogether, the record of misery and slaughter between 1914 and 1945 is horrific. A distinction may be drawn, however, between legitimate military objectives and the gratuitous atrocities of the kind perpetrated by the Germans in the USSR, the Soviets in Germany, and the Japanese in China. The Allied strategic air offensive against Germany had definite military objectives: to inflict the maximum possible damage on Germany’s industrial war-making capacity, to divert German forces—especially air forces—from the fighting fronts to home defense, and to score a decisive victory over the Luftwaffe in the skies over Germany.

These objectives necessarily entailed the death of numerous German civilians.

George Orwell, ever the contrarian, had a robust response to those in Britain who affected to deplore RAF Bomber Command’s campaign against urban Germany:

Every time a German submarine goes to the bottom of the sea, about fifty young men of fine physique and good nerve are suffocated. Yet people who would hold up their hands at the very words “civilian bombing” will repeat with satisfaction such phrases as “We are winning the Battle of the Atlantic.” Heaven knows how many people our blitz on Germany and the occupied countries has killed or will kill, but you can be quite certain it will never come anywhere near the slaughter that has happened on the Russian Front. (“As I Please,” Tribune, May 19, 1944).

Orwell’s general attitude on the subject was that of course, modern war is a disgusting business, but if you accept the necessity of fighting, you must accept the consequences of fighting. Moreover, you must accept that in a such a case as Nazi Germany, the term “innocent civilians” is problematical.

I am not arguing that war should be waged without regard for collateral damage, human or material. Military technology has advanced to a point where good effects on target can often be achieved without “carpet bombing”—an obsolete term of which the enemies of Israel are inordinately fond. America and Israel prove their moral superiority over their enemies by taking advantage of smart munitions technology.

But those enemies do not, nor do they want to. Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, Putinist Russia, seek deliberately to multiply civilian casualties as a terrorist tactic. And it can be seen, if anyone cares to look, that international law is useless against such bad actors. They’ll do as they please, regardless of what the Geneva Conventions say, and there’s nothing to stop them.

Laws selectively applied have no credibility. And laws without police aren’t really laws at all.

The people complaining the loudest about Israel's behavior in Gaza should consider a counterfactual: a Hamas victory over Israel.

That victory would have opened the way for the largest pogrom in history (assuming that the U.S. did not intervene).

Does anyone think that Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Syrians would be more restrained than Hamas on 10/7?

It would have been Nanking spread across Israel.

No. Israel is behaving with remarkable restraint.

Palestine and Hezbollah have for years bombarded Israel’s cities with indiscriminate mass rocket attacks; that they don’t succeed is a lack of ability. Their incompetence does not excuse their viciousness.