Prefatory Note

At The Cosmopolitan Globalist, Claire Berlinski is engaged in an exhaustive analysis of the current crisis of confidence affecting American elites in the time of the Trump restoration. You can read her introduction to this project here. Though I have some substantial disagreements with Claire’s take on Trump and his enemies, it is not my purpose here to argue them. But in Part Three of her analysis, Claire proposes an analogy between France, 1918-1940, and contemporary America that is of interest to me. Historical analogies are always suspect, due mainly to the fact that they’re often pushed too far. As it happens, however, I suggested much the same analogy in this article, published a year ago on Substack. So you see, great minds think alike.

In proposing her version of this analogy, Claire takes as her text L’Étrange Défaite (The Strange Defeat), by the distinguished French historian Marc Bloch. The book was written in white heat, in the immediate aftermath of the 1940 military debacle that delivered France into the hands of the German Third Reich. Perforce, Bloch includes a strident denunciation of the decay and corruption of the French military establishment, which led to the loss of the Battle of France in a mere six weeks—really in just ten days. Not without justification, he links this military defeat with the deeper trends of demoralization, decay and corruption that afflicted French politics and society between 1918 and 1940. But the tale of La débâcle militaire 1940 is not so conveniently summarized.

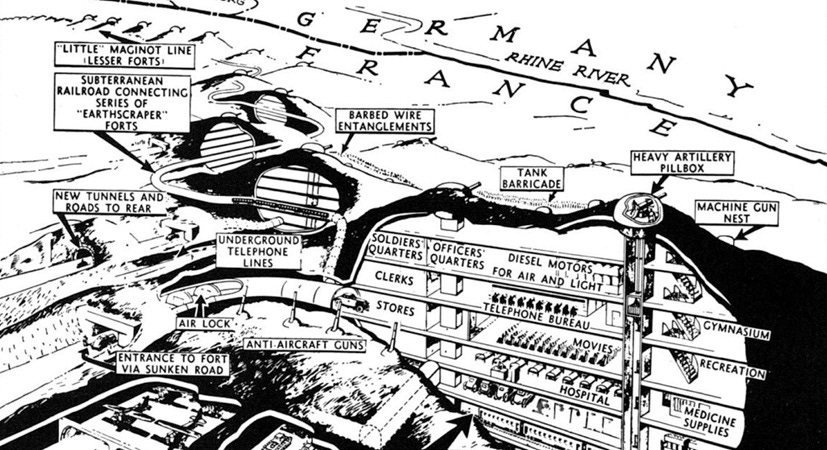

As I mentioned in a comment on Claire’s article, many legends swirl around the military events of May-June 1940, for instance that the French Army, expecting a replay of the static warfare of 1915-18, hunkered down behind its Great Wall, the Maginot Line, while the German Army’s invincible panzers stormed past its left flank. The reality was otherwise. And not to be disregarded is the element of uncertainty in war—which is, after all, an amalgam of rational calculation, guesswork inspired or otherwise, boldness, fear, and the rattle of rolling dice.

That’s the real story of France 1940.

French Defense Policy Between the Wars

The debacle of 1940 grew from roots sunk in the mud of the Great War’s Western Front.

Though on the face of things, France in 1918, triumphant over its ancestral enemy, was the most powerful nation in Europe, the reality was otherwise. The war had inflicted immense damage on the nation—physically, demographically, economically, spiritually. Much of the fighting had taken place on French soil, inflicting terrible damage on the nation’s physical fabric. Proportionately, France suffered higher casualties—killed, wounded, missing in action—than any other belligerent. In total, 1,315,000 Frenchmen died or went missing on the battlefield, representing twenty-seven percent of all men aged between eighteen and twenty-seven. Nearly a million and a half of the 4,200,000 war wounded were permanently maimed. During the war years, there were 1,400,000 fewer births in France than would otherwise have taken place—this in a country whose birthrate was already declining before 1914. These grim realities promoted a spiritual malaise, a depression of national morale, that affected every sector of French society.

This was the background against which French postwar military planning took place. Germany was disarmed, France was the strongest military power on the Continent—but that situation could not be assumed to last forever. Though Germany had been militarily defeated, effectively disarmed, and stripped of important territories, the country’s basic fabric, its power potential, remained intact. What if German power revived? How could France secure itself against that possibility?

Over the course of the 1920s, the general staff of the French Army grappled with that question, and the solution it produced was two pronged. First, the vulnerable sectors of the common frontier with Germany would be covered by a deep belt of fortified localities: the Maginot Line. Second, under the terms of the military alliance with Belgium, the French Army would be prepared to intervene in that country in case of German aggression—for with the common frontier secured, Belgium would be Germany’s only route into France. “We must go into Belgium,” said Marshal Pétain when he was chief of staff in the 1920s. With the common frontier well defended by fixed fortifications, a significant portion of the French Army would be free to advance against the attacking Germans—to fight the decisive battle on Belgian, not French, soil. French soldiers and politicians agreed that the devastation of northeastern France that had occurred in 1914-18 must on no account be allowed to happen again.

The much-maligned Maginot Line was, therefore, a reasonable measure of defense that both economized on troops and narrowed the Germans’ strategic options. Nor was the French general staff wrong in thinking that the Germans, if they came again, would come through Belgium.

As for the French Army’s postwar tactical doctrine it was based, naturally enough, on the lessons of the Great War. It thus emphasized the importance of a well-organized defense, the domination of the battlefield by strong artillery concentrations, and the carefully prepared set-piece attack with tanks in direct support of the infantry. Having learned to its great cost in 1914-18 what modern weapons could do, the French Army placed its faith in firepower over mobility.

This is not to say that French military leaders disregarded the potential of mechanization; they realized that horse cavalry had had its day. In 1931, therefore, the long process of mechanization of the cavalry began. The 4th Cavalry Division was selected for conversion and in 1935 the divisional elements that had so far been mechanized received a separate identity as the 1st Light Mechanized Division (1er Division Légères Mécanique or 1st DLM). At the beginning of the war there were two DLMs in the Army’s order of battle, with one more in process of formation. The designation light for these divisions was something of a misnomer, denoting their ability to deploy rapidly rather than their size or equipment. In fact, they were well-organized, well-equipped armored divisions that compared favorably to the German Army’s panzer divisions.

The French Army’s other major mechanized formation was the armored division (division cuirassé or DC), equipped with heavy tanks. The DC was conceived as a “breakthrough division,” opening the way for the infantry in the attack. Three of these divisions were in existence in 1939 and one more was forming.

Significantly, however, the French Army had evolved no unified tactical doctrine for the employment of tanks. Unlike the German Army, which brought all mechanized forces together in a single arm of the service—the Panzerwaffe—French tanks were shared out between the cavalry and infantry arms. The light mechanized divisions and the partially mechanized light cavalry divisions (divisions légères de cavalerie or DLC) received light and medium tanks; the armored divisions had light and heavy tanks. Organizationally, the three division types were quite different, and they were not intended to operate together.

Also unfortunate was the combination of mechanized formations with horse cavalry in the light cavalry divisions. Because of the difference in capabilities between mechanized and mounted units, they could not easily coordinate their actions or provide useful mutual support. And finally, a large number of tanks were allotted to twenty tank groups (groupes de bataillons de chars), two or three battalions strong, earmarked for direct support of the infantry. The existence in 1940 of the light cavalry divisions and tank groups shows that the French Army's senior leaders had not really grasped the full military potential of mechanization.

May 1940: The Opposing Forces and Plans

In May 1940, on the eve of the German invasion, the mobilized French Army comprised three armored divisions (with one more in process of formation), three light mechanized divisions (really armored divisions), seven motorized infantry divisions, five light cavalry divisions (partially mechanized), 101 infantry divisions (including North African and colonial units) and thirteen fortress infantry divisions. Of these, ninety-one infantry divisions and all the others listed were in metropolitan France. There were also a number of separate mechanized brigades and horse cavalry brigades.

The French Army could count on the support of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) with its ten motorized infantry divisions, one tank brigade and two armored reconnaissance brigades. Also expected to be included in the Allied order of battle was the Belgian Army (twenty infantry divisions, two motorized cavalry divisions), and possibly the Dutch Army (ten infantry divisions).

For the campaign in the West, the German Army had available ten panzer (armored) divisions, eleven motorized infantry divisions (including three SS-VT formations), 129 infantry divisions, three mountain infantry divisions, one horse cavalry division, and the equivalent of two airborne divisions.

As noted above, French tanks not assigned to the armored, light mechanized, and light cavalry divisions were mostly in tank groups of two or three battalions each, tasked with the mission of infantry support. The French Army had 3,254 tanks in total, and though some models dating from the First World War remained in service, many were modern and in terms of firepower and armor protection they generally outclassed the 2,439 tanks at the disposal of the German Army. However, all German tanks were concentrated in the ten panzer divisions. In other classes of weaponry, the two armies were roughly comparable.

Overall, therefore, the two sides were evenly matched, with a slight advantage going to the Allies. Only in the air did the Germans enjoy a significant margin of superiority, and this was to be a major factor in the outcome of the battle.

As noted above, the French High Command expected a German offensive to come through Belgium, as it had in August 1914. It planned, therefore, for a rapid advance into Belgium as soon as the Germans violated that country’s neutrality, so as to check the enemy before he could reach French soil. Though at the instigation of King Leopold III, Belgium withdrew from its alliance with France and declared neutrality in October 1939, the French still intended to move into Belgium. But now that operation could not be coordinated in advance with the Belgians, and could not commence until the Germans actually invaded—two significant drawbacks.

All in all, however, the French high command’s appreciation of enemy intentions was reasonable enough. And indeed, in its original form the German plan, codenamed Fall Gelb (Case Yellow) was a somewhat less imaginative variant of the famous Schlieffen Plan: a drive through Belgium and into France, terminating on the line of the Somme River. The German General Staff regarded this operation as nothing more than the first phase of a protracted campaign.

After the conquest of Poland, Hitler began pressuring the Army to launch its attack in the West as soon as possible: a prospect that unnerved his senior officers, who were all too well aware of the Army’s lingering deficiencies. Fortunately from their point of view, the winter of 1939-40 was one of the worst in many years, and the attack in the West had repeatedly to be postponed. Then, when a copy of the Fall Gelb operations order fell into the hands of Dutch military intelligence, those staff officer and commanders who had been advocating a quite different plan got their opportunity to present their ideas to the Führer.

The Manstein Plan, as it came to be called after the officer chiefly responsible for its formulation, replaced the drive through Belgium toward the Somme with a drive through the hilly, heavily forested area called the Belgian Ardennes toward the Channel coast in the vicinity of Abbeville. Farther north, a German advance into Belgium and the Netherlands would function as a “matador’s cloak,” distracting Allied attention from the Ardennes. If all went according to plan, the armies of the Allied left wing would move into Belgium, there to be trapped and annihilated as the main German attack cut their rear communications.

This revised plan, informally christened Sichelschnitt (cut of the sickle) fired Hitler’s imagination, and he approved it—time and chance having conspired to bring it to his attention.

A Battle Lost

The sad tale of the 1940 Battle of France may briefly be summarized as follows. The German offensive commenced on 10 May with the invasion of Belgium and the Netherlands. The Allies reacted promptly and according to plan, sending the armies of their left wing into Belgium with the mission of establishing a line of defense on the Dyle River.

The right flank of the Allied advance pivoted on the Belgian Ardennes, which occupied the gap between it and the Maginot Line’s northwest terminus. The French high command judged that the Ardennes terrain was too rugged for a rapid, large-scale deployment of mechanized forces. This judgement was reinforced by a 1938 war game whose results suggested that if the Germans attempted such an operation, there would be plenty of time to bring up reinforcements to deal with it. Accordingly, the sector was covered by a single army including low-grade reserve infantry divisions, understrength and armed largely with obsolescent weapons.

The German “matador’s cloak” in the Low Countries performed just as intended, fixing the attention of the French high command in that direction while the blade of the sickle—six panzer divisions and three motorized infantry divisions—advanced through the Ardennes toward the line of the Meuse River. With the Luftwaffe’s Stuka dive bombers acting as “flying artillery,” the panzers shattered the French divisions facing them, crossed the Meuse, and drove on toward the Channel coast.

By the time that the French realized what was happening, only the most energetic measures could have retrieved the situation. But their reaction was anything but energetic. Counterattacks were ordered, but they were poorly coordinated and came to nothing. By 20 May, leading elements of the German advance reached the mouth of the Somme River on the Channel coast. The cut of the sickle had thus severed the rear communications of the Allied right wing, which included the best divisions of the French Army and most of the BEF. Counting the Dutch and Belgian armies, this encirclement cost the Allies some sixty divisions.

Though the fighting raged on for another month, the issue was never in doubt. In just ten days, the German Army had won the Battle of France.

The Anatomy of Defeat

As the foregoing sketch suggests, the strictly military causes of France’s 1940 debacle were nothing out of the ordinary. Military history records many similar tales of woe. A divided and lethargic high command, faulty strategic and operational assumptions, ill-conceived tactical doctrine—all these things affected the outcome. But it’s not true, as often alleged, that the French Army fought poorly. Though the reserve divisions holding the Ardennes sector were routed, other French units, for instance the light mechanized divisions in Belgium, performed admirably. Indeed, the DLMs proved themselves a match for the German panzer divisions in a stand-up fight. And in the second phase of the campaign, despite the odds against it, the French Army put up stiff resistance before succumbing to the inevitable.

Nor can it be said that the existence of the Maginot Line was a factor in the French defeat. On the contrary, it served precisely the purpose for which it was built. By securing the common frontier between France and Germany, the Maginot Line enabled the French Army to concentrate its best divisions for what was expected to be the decisive battle in Belgium. It was that misconceived plan of campaign, not the Great Wall of France, which set up France and its allies for defeat.

The French Army’s tactical doctrine, which failed fully to exploit the possibilities of mechanization, may be said to have played a secondary role in the debacle. An examination of the French order of battle reveals that there were sufficient modern tanks available to create several additional armored divisions. For instance, the five light cavalry divisions each contained a horse cavalry brigade and a light mechanized brigade. The latter could well have been used to form two or three light armored divisions, perhaps with an additional tank battalion coming from the separate tank groups. By themselves, however, such measures would not have compensated for the French high command’s fatal strategic and operational blunders.

The element of chance, however, weighed in heavily. The bad winter weather that forced the German offensive to be postponed gave time for a drastic revision of Fall Gelb to be developed and approved. Had the original plan been followed, the French Army would have had the opportunity of fighting its anticipated battle in Belgium, possibly with success. Even if defeated in such a battle, the Allies would not have sustained the catastrophic losses they sustained in reality.

Still, for all its shattering impact, La débâcle militaire 1940 did no more than put a period to the long story of France’s decline and fall. It was not so much the magnitude of the defeat suffered but the French nation’s reaction to it exposed the long-maturing demoralization, decay and corruption so lamented by Marc Bloch. France, once the foremost country of Europe, a great power, a beacon of culture and civilization, stood revealed in the eyes of the world and of its own people as an empty vessel, defeated, bitterly divided along class and political lines, drowning in despair. The fit symbol of this debased France, an abject vassal state of the Third Reich, was its new chief of state: Philippe Pétain, Marshal of France, hero of the Great War, now an old man, a confirmed pessimist, a bitter enemy of democracy who was all too willing to find for France a place in Hitler’s New Order.

When Rommel came to the Meuse near Dinant, he found a bridge intact, with the French artillery on the heights above. He couldn’t believe his luck and rushed his tanks across the river, all the while expecting the French to wake up and wreck his plans. They never did (they were awaiting orders that never came). It was luck like this that favored the Germans throughout the campaign.

As for the French reaction, many saw Hitler as the savior of what they regarded as a hopeless societal malaise. Many others, my nanny among them, wanted no part of the fight between the foreigners and the French oligarchy. She owned a cafe frequented by resistance terrorists and the site of multiple German reprisals, yet like many, she never picked a side in a war that had nothing to do with her.

History is written by the victors and rarely resembles actual events. Events tend to be sloppy and messy and are almost never resolved one way or the other. But if we’re going to celebrate myths, you can’t do much better than the Allied version. Just don’t fight your next war on that basis.

Interesting, but I cannot see any resemblance between France in 1940 and USA now. True, both nations are overwhelmed be defeatism, but the Americans want to surrender Ukraine and Taiwan without a fight. Much more like Munich in 1938.