The idea that wars are there to be won seems to have gone right out of the thinking of today’s American military leadership and that of its political masters. One has only to review Donald Trump’s vacuous prattle about the Russo-Ukrainian War to see that. He speaks of peace in the abstract: merely, an end to the fighting. What kind of peace, though? That is, or ought to be, the relevant question. But in the corridors of power, it’s either scorned or simply ignored.

If the President supplies today’s foremost example of this muddled thinking, there are many others, stretching back to the Vietnam War. Over the decades, a belief has grown up that a war is something to be managed, not won. With the advent of the Kennedy Administration the focus of American strategic thinking shifted from the nuclear balance of terror and the core doctrine associated with it: massive retaliation. The Eisenhower Administration had embraced this doctrine, partly as a cost-cutting measure.

It was thought that a powerful nuclear deterrent would be cheaper to create and maintain than broad-spectrum armed forces, suitable for multiple contingencies. Intercontinental ballistic missiles, long-range strategic bombers, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, constituted the American “strategic triad,” which was mirror-imaged by the Soviet Union’s own strategic forces. Implied in this was a belief that any military conflict between the superpowers would escalate into all-out global nuclear war. And that belief would preserve the peace—because for both sides, the risks associated with war were literally unthinkable.

This strategic vision recalled the preachings of the airpower prophets in the years between the world wars. They had argued that strategic bombing, directed against an enemy nation’s heartland, could destroy its industrial base and shatter the morale of its civilian population: a massive knockout blow that would terminate the war in short order. The legacy military branches, the army and the navy, would become mere auxiliaries of the air force, the arm of decision. But World War Two revealed a considerable gap between theory and practice. Only with the development of nuclear weapons was that gap closed.

Massive retaliation had its critics in and out of government. For instance, Mordecai Roshwald’s 1959 novel, Level 7, depicted a mechanism of nuclear war so automated that human participation was confined to the pressing of a few buttons, and so programmed as to exclude any military action short of all-out global nuclear war.

Among those who were ill content with the balance of terror were the bright young men who came in with John F. Kennedy. Was it really true, they asked, that any military conflict between the superpowers must culminate in global nuclear war? Must the only response to Soviet aggression be massive retaliation? Suppose deterrence failed? These nagging questions gave birth to the strategy of flexible response, which was soon embraced by the new administration. Going forward, the US and its allies would maintain military forces capable of countering aggression at a lower level of conflict. In place of massive retaliation there would be an escalatory ladder, providing opportunities to end a war at some lower level of conflict.

Flexible response dovetailed with another strategic fad of the Kennedy era: counterinsurgency (COIN) warfare, which attracted attention as decolonization reshaped the Third World. There, it was argued, the superpowers would seek to cultivate clients among both the new nations of Africa and East Asia and existing regional powers like Iran and India. A country might be worth cultivating because it was rich in resources—oil for instance. Or it might provide bases for forward-deployed forces—Subic Bay and Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines for instance. And occasionally, somewhere in the Third World, some country might be the venue for a proxy war, with the superpowers sponsoring rival factions—Vietnam for instance.

Counterinsurgency warfare doctrine was billed as a sophisticated politico-military enterprise in which actual warfighting was merely one aspect of the overall strategy. Political tutelage, economic development, social reform, “winning hearts and minds”—the military effort would be coordinated with these non-military projects. No longer would soldiers be limited to the pursuit of victory in battle. They’d also be expected to serve as role models, mentors, teachers, builders—nation building, as these activities came to be called. It was, so to speak, the foreign policy equivalent of the Johnson Administration’s ambitious domestic program, the Great Society.

COIN was a good fit with the Kennedy Administration’s New Frontier conceit. Its proponents marketed it as amalgam of sophisticated analysis, innovation, and idealism. The target audience was the rising generation of American leaders, a cohort naturally disposed to view war as a multi-faceted management challenge.

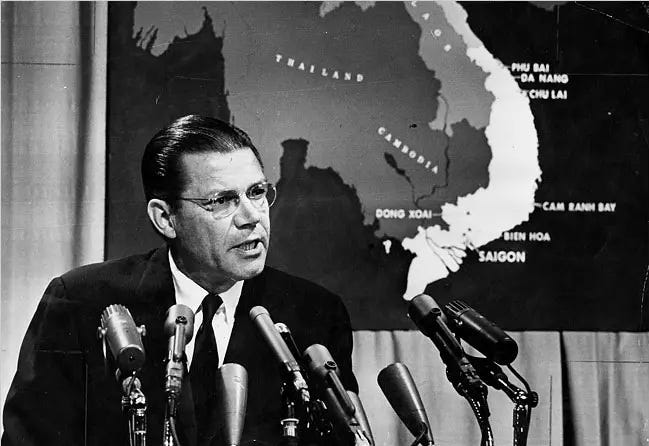

Robert Strange McNamara, Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, was the ultimate exemplar of this mindset. Born in California, educated at the University of California, Berkeley, and Harvard Business School, he had served in the US Army Air Forces during World War Two, primarily as a statistical analyst in the Pentagon. After the war, Henry Ford II hired McNamara and a cohort of USAAF veterans—nicknamed the Whiz Kids—to develop modern management, planning, and organizational systems for the financially troubled Ford Motor Company. McNamara himself served briefly as president of the company from 1960 to 1961, when JFK nominated him for Secretary of Defense.

As SecDef, McNamara introduced some salutary administrative reforms, such as the consolidation of DoD intelligence functions in a new Defense Intelligence Agency. But McNamara, the ultimate Organization Man, was out of sync with the senior leadership of the armed forces: men like General Curtis Lemay, Chief of Staff of the Air Force between 1961 and 1965. These senior officers, who’d held combatant commands during World War Two, doubted that modern management techniques were broadly applicable to actual warfighting. Theirs was a more traditional conception of war in which rational calculation was but one aspect of command: War was also the theater of primitive emotions and of the element of chance, in much the sense of Carl von Clausewitz’s characterization of war’s character as a “fascinating trinity.”

In Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam, H.R. McMaster records how this disconnect helped to precipitate America into its costly and ultimately futile military adventure in Vietnam. The Joint Chief never really accepted the strategy that McNamara sold to LBJ: a campaign of “graduated pressure” that would eventually bring North Vietnam to the conference table while limiting American liability. In this the SecDef was catering to his president’s political priorities: Vietnam must not be allowed to derail LBJ’s 1964 presidential campaign, nor his ambitious domestic program, the Great Society. McNamara was confident that the Vietnam War could be managed to that end.

But though the Joint Chiefs dissented from the strategy of graduated pressure, they never made this plain to the commander-in-chief. The principle of civilian control of the military was deeply implanted in these men. And no doubt, their reluctance to speak up was buttressed by LBJ’s reminder to them that he was the coach and they were on his team. Nevertheless, McMaster fingered their silence as one facet of the dereliction of duty that led to an open-ended Vietnam commitment.

The outcome, of course, was defeat—not defeat on the battlefield, but defeat on the home front. Graduated pressure, based on the delusion that violence could be carefully calibrated to produce the desired result, merely prolonged the war. The American commitment grew and grew, from the initial 5,000 Marines deployed to Vietnam in 1964, to over half a million by 1968. This was a force more than sufficient to defeat North Vietnam—but victory as traditionally defined was not the American objective. It was a situation that domestic public opinion would not tolerate in the long run, as casualties multiplied to no apparent purpose, and it destroyed Lyndon B. Johnson’s political career.

LBJ’s successor, Richard Nixon, had a better understanding of the realities. Elected president in 1968, he entered office with a mandate to end America’s military involvement in Vietnam. And within the political constraints imposed on him, Nixon and his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, did precisely that. By threatening North Vietnam with escalation and proving that it meant business, the Nixon Administration eventually forced North Vietnam to the conference table. The resulting Paris Peace Accords (1973) extricated the US from its direct military commitment to South Vietnam, with reasonable prospects for that country’s survival.

But as if some malign spirit of history had laid a curse on America’s involvement in Vietnam, the Watergate scandal destroyed the Nixon Administration and with it the American guarantees to South Vietnam that were embodied in the peace agreement. And so the war ended in 1975, with the fall of South Vietnam.

But unfortunately, the belief that war is a problem of management lingered on—and its effects, large and small, continue to distort American strategic thinking. Again and again, an obsession with process has distracted political and military leaders from the fundamental question: What is the definition of victory?

Disregarding minor military operations like the invasion of Grenada (1983) and the invasion of Panama (1989), the only US military operation for which clear-cut victory conditions were set was Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm. Those victory conditions were (1) deterring an Iraqi attack on Saudi Arabia and (2) the ejection of Iraqi forces from Kuwait and the restoration of that country’s sovereignty. Both were met. Though subsequent criticisms involving the US-led coalition’s failure to follow through by deposing the Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq had some validity, they were based on the argument that the second victory condition ought to have been expanded, not that it wasn’t met. On its own terms, Desert Shield/Desert Storm was an unqualified success.

The same cannot be said of the long, costly, and ultimately unsuccessful war in Afghanistan (2001-2021). Though the initial objective, the ejection of the Taliban from power, was met, the war soon devolved into a military counterinsurgency campaign with features of nation building, very reminiscent of Vietnam. But due to the primitive state of the country and its tribal factionalism, there was even less likelihood of success. US forces found themselves fighting a Taliban insurgency, training a new Afghan army and police force, and laboring at nation building. Commanding generals came and went, each with his plans for jump-starting the military effort, such that it eventually became impossible to state victory conditions. By the end of the first Trump Administration, the war was effectively stalemated, with neither the Afghan National Government nor the Taliban in a position to win, a small American ground force in place though not engaged in combat, and the Afghan armed forces still largely dependent on American logistical support.

When President Biden withdrew the American presence force and terminated American logistical support, the end came swiftly. Today the Taliban is back in power, and the memory of the disgraceful rout that Biden engineered remains as an ugly blot on the honor of the United States.

Much the same thing happened in Iraq in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion and Saddam Hussein’s overthrow: Hard on the heels of a seemingly impressive military victory came muddle, confusion and, eventually, a bug-out ordered by President Barack Obama, who craved the credit for ending a war and realized, perhaps subconsciously, that the quickest way to end a war is to lose it. Fortunately, the consequences of that needless retreat, though bad enough, were not as terrible as the sequel in Afghanistan. Today, for all the mistakes made by American leaders, military and civilian, Iraq is better off than it was under the boot of Saddam Hussein’s fascistic regime.

America’s involvement in the major conflict of the moment, the Russo-Ukrainian War, is peripheral. No US military forces are engaging the Russian armed forces in combat. But under Biden and now Trump, the old story of muddle and confusion, the failure to establish a clear policy and formulate a definition of victory, is repeating itself.

When the war began, the Biden Administration assumed that it would end quickly, with Russia victorious. This assumption was the product of an intelligence failure: The combat effectiveness of the Russian armed forces had been grossly overrated. When this became clear, Biden committed America to a policy of support for Ukraine. Military aid was provided. But to what end? In the background of the President’s tough talk, timidity, uncertainty, fears of escalation, dominated the Administration‘s thinking. The military aid provided was sufficient to keep Ukraine in the fight, but not enough to achieve a clear-cut victory over the Russians, and the net result was stalemate. By trying to mange the war instead of trying to win it, Biden botched Ukraine.

Thanks to the Biden Administration’s incompetence, the US committment to Ukraine was inherited by Donald Trump, who during the 2024 election made it clear that he intended to end the war and liquidate that committment.

Trump’s approach is influenced primarily by personal conceit: In his own mind, he’s a master of the art of the deal. All that was necessary, he thought, was to get the two sides talking, leading to some kind of win-win agreement. The details, however, were not—still have not—been made clear. And, of course, none of the people around him, some of whom must have known that his take on the situation was delusional, were prepared to tell him that.

Wars do not end with win-win peace agreements. The treaties that terminate wars reflect the fact that one side has been victorious, one defeated. The margin of victory and defeat may be narrow, but it’s always there. And until it appears, neither side will be willing to make a deal. Trump only discovered this when he tried to strong-arm Ukraine into making concessions to Russia. But President Zelensky balked, leading to the notorious Oval Office blowup. And on the other side, V. Putin summarily rejected Trump’s cease-fire proposal. His position is that Russia will be prepared to suspend military operations and talk peace only after all of its demands are met.

So much for the art of the deal.

President Trump, like so many American leaders before him, views war as a management problem—in his case, perhaps, more as a business transaction. He sees that to end the war, the billigerents must get to yes. But he can’t see that fighting is how they get to yes. The Grand Alliance and Nazi Germany only got to yes when the latter’s hopeless military position left it no other option but unconditional surrender.

Trump’s policy on the Russo-Ukrainian War has not the psuedo-intellectual backing of some whiz-bang doctrine like flexible response or graduated pressure. It’s backed only by personal hubris and conceit. But its effect is much the same: process as strategy. If we try really, really hard, we can make the North Vietnamese see reason, we can transform Afghanistan and Iraq into modern democratic states, we can get V. Zelensky and V. Putin to sink their differences and shake hands.

It doesn’t work that way. And the unwillingness of presidents, secretaries of state, generals, admirals, and other leaders to admit what it takes to get to yes guarantees that the misfortunes, failures and debacles of the past eighty years will be repeated over the course of the present century.

Very potent argument. There was an excellent article over at Tablet recently about the American move away from winning wars to limiting and managing them, with some telling criticisms from an Israeli point of view.

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/why-america-stopped-winning-wars