At the beginning of the First World War the airplane was viewed with skepticism by senior military commanders—who thought that at most, it might be a useful supplement to cavalry in the reconnaissance role. But by Armistice Day 1918 the airplane had matured into a formidable weapon of war. It first proved itself as an instrument of tactical reconnaissance, a mission it carried out far more effectively than cavalry. Each side thereupon sought to counter the other’s aerial reconnaissance activities by developing armed pursuit aircraft, and soon these were engaging one another in air-to-air combat. Meanwhile the larger two-seat reconnaissance and observation aircraft acquired armament and assumed an active combat role, bombing and strafing enemy ground targets. And if the enemy’s forces in the field could be bombed, why not his rear communications, war industries, railroads—even his cities?

This idea of using airplanes to attack the enemy’s homeland was not a new one. It was a staple of prewar fantastic fiction, for example in H.G. Wells’ 1914 novel The World Set Free (which also contained a prediction of atomic weapons). During the Great War the first such air attack occurred on the night of 24–25 August 1914, when a German Zeppelin (airship) dropped bombs on the Belgian city of Antwerp. The first sustained strategic air offensive was conducted by Germany against Britain between 1915 and 1918. These attacks were carried out initially by Zeppelins, later supplemented by the twin-engine Gotha bomber, which had been specifically developed for the purpose. Though they caused comparatively little damage, the German air raids both outraged and alarmed the British government and public, causing significant resources to be diverted from the fighting fronts to home defense.

The Allies in turn carried out sporadic air attacks on cities in western Germany between 1915 and 1917, and the idea of strategic bombing gradually gained supporters. By 1918 Britain’s Royal Air Force (established on 1 April of that year by amalgamating the Army’s Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service) possessed a strategic air arm in the form of the Independent Bombing Force (IBF). Beginning in June of that year the IBF conducted a strategic bombing offensive by day and night against transportation and industrial targets in western Germany. But these attacks coincided with the German Army’s great final offensive on the Western Front, and the IBF was frequently diverted from its strategic mission to provide air support for the Allied armies.

As with the German raids on Britain, the RAF’s 1918 strategic bombing campaign caused no very serious damage to German industries or cities, and many aircraft were lost. But they were thought to have shown promise and plans were drawn up for a much more powerful effort in 1919—short-circuited by the collapse of German resistance in the autumn of 1918.

The end of the war brought problems for the RAF, its continued existence becoming a subject for acrimonious debate. The Army and the Royal Navy had been less than pleased to give up their air arms to the new service and in the first years of peace there were repeated calls, particularly from the Navy, for the abolition of the RAF—supposedly as a cost-saving measure.

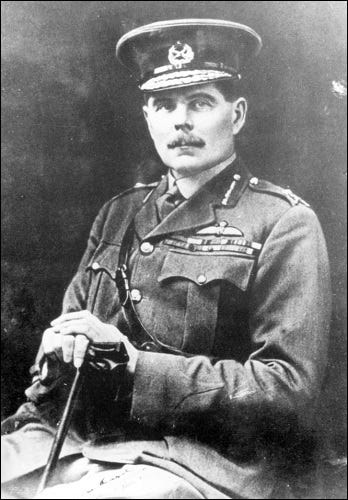

Necessity is the mother of invention, and to some extent sheer self-preservation motivated the postwar RAF’s fervent embrace of the doctrine of strategic bombing. In response to Army and Navy arguments against the continued existence of their service, the RAF’s leaders, with the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard, at their head, argued that the future of war belonged to the air. The RAF, they claimed, would take the fight directly to the enemy’s heartland, destroying his war-making capacity and national morale by bombing. They predicted that in the near future, airpower would relegate the other armed services to secondary roles.

But during the 1920s, parsimonious defense budgets frustrated the RAF’s hopes for the creation of a strategic air force. The requisite aircraft and infrastructure did not exist and the British government, anxious to reduce defense spending to an absolute minimum, would not give the necessary money to develop them. Trenchard only kept the RAF going by showing that air power could be a cost-effective instrument for policing the empire. In Iraq and on India’s Northwest Frontier, a few bombs usually sufficed to call rebellious tribes to order, and most of the aircraft procured for the RAF in the postwar decade were designed for that mission.

Even so, the concept of strategic bombing, fostered by prophets of airpower like Trenchard, Billy Mitchell in the United States and Giulio Douhet in Italy, captured the popular imagination. Arguing that the airplane was destined to become the “winning weapon,” the airpower prophets envisioned a massive aerial knockout blow that would shatter the enemy’s war-making capacity and his will to resist within days or even hours of a declaration of war. This was an idea that came to be widely accepted. Science fiction novels like Wells’ The Shape of Things to Come and Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men presented just such alarming depictions of future wars—which were all too credulously accepted.

More prosaically, debate in military circles revolved around the validity of the airpower prophets’ vision. In Britain, for instance, there were sharp disagreements over the effectiveness of air defenses: fighter planes and antiaircraft guns. Most RAF leaders argued that attack was the best defense; priority should therefore be given to the development of a strategic air arm. Others in the RAF, the other services and the government were not so sure, though Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, echoing Douhet, opined that “the bomber will always get through.”

By the mid-1930s, with Hitler in power, German rearmament underway and the threat of a new European war looming larger by the year, the debate over strategic bombing sharpened. The Nazi propaganda machine’s extravagant claims regarding the newly established German air arm, the Luftwaffe, tended to be uncritically accepted in other countries. The frightful prospect of London and Paris laid in ruins by bombs, their populations slaughtered in droves, was very serviceable to both German diplomacy and to the French and British antiwar movements. Yet frightening as they were, such predictions of disaster failed to prevent the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939. And as the sirens wailed in London on the day that Britain declared war on Germany, it remained to be seen how accurate they would prove to be, when put to the test.