A Tale of Two Republics

The circumstances of their birth foreshadowed the manner of their death

This comment on my just-published article, “Decline and Fall,” raises a point worth consideration. Readers will remember that in my article, I proposed the history of the French Third Republic as a better historical analogy for present-day America that the German Weimar Republic. In her comment on this, my interlocuter observed:

I think a key point missing in analyses of this genre is a country’s history of democracy, and the value the culture places on democratic rule. Germany had basically zero historical or cultural appreciation for democracy. France was not a longstanding democracy either, though not as distant from democracy as Germany was.

This is indeed a valid point. But that bedrock weakness was exacerbated by the circumstances of the birth of the French and German regimes under discussion. Both the Third Republic and the Weimar Republic were born in the aftermath of defeat in war at a time of great instability, with revolution in the air.

In 1870-71, the forces of the allied German states under Prussian leadership crushed the French Army, driving Louis Napoleon from his throne, securing German unification, and touching off bloody civil conflict in France: the Paris Commune and its suppression by the “forces of order.” The provisional French government that ruled France in the aftermath of this debacle was largely conservative and monarchist in sentiment, and the only reason that the Third Republic was established was that the monarchists were divided into three factions—Bourbon, Orléanist, Bonapartist—and could not agree on a candidate for the throne. From the beginning, therefore, the Third Republic was hobbled by the fact that it was many Frenchmen’s second choice.

A fuller account may be found in “Decline and Fall”; see below.

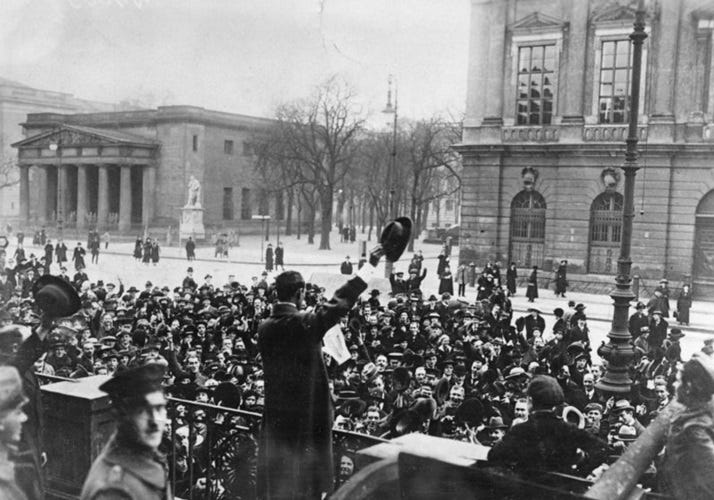

The birth of the Weimar Republic was even more fraught. It took place in the immediate aftermath of defeat in war, with the Kaiser dethroned, the armed forces in dissolution, and the threat of a communist revolution apparently imminent. The proclamation of a German Republic on November 9, 1918, was a unilateral action of doubtful legitimacy taken in an atmosphere of threat and uncertainly. It was carried out by the German Majority Social Democratic Party in an attempt to forestall a communist coup, though not without dissention within the MSDP leadership. In the circumstances, however, it had to be accepted as a fait accompli and the High Command of the Army pledged its support for the new regime, “to prevent the worst from happening.”

The constitution of the German Republic was promulgated by an elected National Assembly, assembled in the city of Weimar, on August 11, 1919. But the circumstances of the new regime’s birth generated resentments and divisions that undermined its legitimacy in the eyes of many Germans. The Weimar Republic, as it came informally to be called, was made to bear the responsibility for the “Shame of Versailles,” the 1919 peace treaty that effectively disarmed Germany, stripped it of significant territories, saddled it with war reparations and laid upon it the responsibility and guilt of provoking the late war. This was a national humiliation that almost all Germans agreed must be wiped away. And the Republic was identified with that humiliation. It was also identified with the inflation crisis of the early Twenties, a traumatic event that wiped out the savings of the thrifty German middle class while letting debtors off the hook and enriching speculators.

Another insoluble problem for the Weimar Republic was that key groups—big business, large landowners, the state bureaucracy, the judiciary, the officer corps of the Army—never really accepted its legitimacy. Well represented as they were in the traditional conservative parties, these people looked forward to a day when the Republic could be replaced by an authoritarian regime that would cast off the shackles of Versailles and restore Germany to its rightful position in Europe and the world. Hitler was to make effective use of these discontents during the Kampfzeit, the “time of struggle” for power. In his telling, the founders of the Republic were the “November criminals” who in 1918 stabbed Germany and its heroic Army in the back, snatching defeat from the jaw of victory.

The Nazi Pary’s rallying cry, Deutschland Erwache! (Germany Awake!) summed up that message.

Yet all might have been well had it not been for the Great Depression. By the mid-Twenties, it appeared that the postwar crisis had been mastered. Political violence subsided, prosperity returned, European peace seemed secure. But the Depression devastated the German economy, with unemployment and impoverishment soaring into the stratosphere. The years 1930-33 witnessed the terminal crisis of the Weimar Republic, when economic collapse, political paralysis, festering divisions and old discontents combined to clear the way for Hitler’s ascent to the chancellorship.

One could say, indeed, that liberal democracy perished in Germany some years before Hitler came to power. The Reichstag became politically deadlocked with no party or coalition of parties able to form a government based on a parliamentary majority. The last three governments before Hitler’s had therefore to rely on a provision of the constitution providing for rule by presidential degree in an emergency. Finally, however, the aged president, Field Marshal von Hindenburg was persuaded to accept a coalition government of the parties of the Right, with Hitler as chancellor and a cabinet made up largely of non-Nazi conservatives. He did so with some reluctance, having previously remarked that “Herr Hitler” might do as Minister of Posts, but certainly not as chancellor.

Once in power, Hitler wasted little time in sidelining his coalition partners and consolidating supreme power under the banners of the Nazi Party. When Hindenburg died in the summer of 1934, Hiter became Führer und Reichskanzler, combining the offices of head of state and head of government. In this way the moribund Republic met its end.

The lack of democratic traditions may indeed have played a role in the fall of the Third Republic, though the circumstances of its birth, social and economic problems, the death and destruction of the Great War, and the failure of national will and moral were the more immediate causes. And it should be noted that despite everything, the Third Republic did last from 1875 to 1940. But the Weimar Republic lasted a mere fourteen years, with only a brief interval of stability before its swift destruction.

If the democratic tradition in France was uncertain, at least it existed. In Germany, however, it was nonexistent. The failure of the 1848 revolution and the manner of Germany’s unification in 1870-71 saw to that. Those many Germans who judged the Weimar Republic and found it wanting had either the authoritarian past or present communism as a potential replacement. Most of them chose a return to the past, not realizing that Hitler was neither Frederick the Great, nor the Kaiser, nor Bismarck—no stabilizing force, no guardian of tradition, but V.I. Lenin in a brown shirt.

Has there ever been a republic so thoroughly set up to fail as the Weimar? The Allies thought that removal of the German tools of war would pacify them, but the greatest tool of all was the national character and consensus, which never much wavered between 1914 and 1945. Prosperity might have temporarily softened the desire for another round, just as defeat had soured it, but neither eliminated it.

I’m with your proposition that the French experience fits ours better than the German, but not because of a lack of a democratic tradition. All societies find a way to represent the popular will, either explicitly or via the organizations of the state. And the German popular will was clearly for a rematch. Hitler wasn’t so wildly popular because of some form of mass hypnosis, but because he delivered what the Germans wanted.

Thank you. Hitler is Lenin in a brown shirt - a very good description.

I have always wondered why many people call Hitler and the National Socialists right-wing. They have all the hallmarks of leftist ideologies, leftist submission to the majority, leftist ideology, the leftist idea of state dictatorship "for the good of the people".