Note for Substack Readers

This essay was originally published in 2020 on my website devoted to military history, THE WAR ROOM. It has been revised and edited for publication here.

Introduction

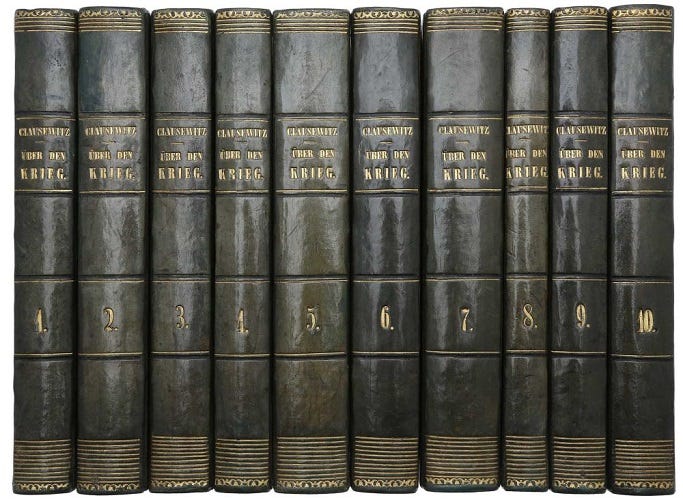

No student of military history can bypass Carl von Clausewitz’s On War, without doubt the most famous—and controversial—treatise on the subject ever written. The sophistication of Clausewitz’s approach and the depth of his analysis have never been surpassed—but these very qualities have caused readers and critics to misunderstand or even distort his philosophy of war. For philosophy of a kind it surely is: a rigorous, systematic investigation in pursuit of fundamental truth. What is war? Clausewitz asked. He spent his life in a quest for the answer.

In an essay of this length the thesis of On War can only be outlined. For the benefit of readers seeking more information, a bibliographical note is provided.

Biographical Sketch

Carl Philip Gottlieb von Clausewitz was born on 1 June 1780 at Burg bei Magdeburg in the Duchy of Magdeburg, a province of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, itself the core territory of the Kingdom of Prussia. He was the youngest of four sons. His father, a former Army officer, was employed in the Prussian revenue service. His family claimed noble status on the basis of descent from the barons of Clausewitz in Upper Silesia—a claim that while dubious was eventually recognized by the King of Prussia. Clausewitz entered the Prussian Army in 1792 at the age of twelve, his rank of lance corporal (Gefreiterkorporal) marking him out as an officer candidate. After two years of service in the ranks he was duly commissioned as an ensign in the prestigious 34th Infantry Regiment, whose colonel-in-chief was Prince Ferdinand of Prussia, the younger brother of Frederick the Great.

In 1810 he married Countess Marie von Brühl, the daughter of a socially prominent family. This match, which proved exceptionally happy, put Clausewitz in touch with Prussia’s leading literary and intellectual figures. Marie, who was well educated, was influential in her husband’s intellectual development. After his untimely death she edited and published his complete works.

Clausewitz served throughout the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars and was closely involved in the Prussian reform movement that sprang up after the country’s catastrophic defeat at the hands of Napoleon in 1806. He became an aide to Gerhard von Scharnhorst, the moving spirit among the military reformers who sought to rehabilitate and modernize the shattered Prussian Army. This proved professionally unfortunate for Clausewitz, since many of the proposed reforms were bitterly opposed by the conservatives around King Frederick William III. The young officer acquired the reputation of a liberal, and this to some extent blighted his career. As a soldier and a Prussian patriot, Clausewitz passionately aspired to high command, but the King's suspicion of him frustrated that ambition. Though Clausewitz saw a good deal of active duty, he never had the chance to make history on the field of battle: a bitter personal disappointment.

Even so, Clausewitz had a respectable military career. The wars over, from 1816 to 1830 he served as director of the Prussian War Academy (Kriegsakademie), eventually rising to the rank of major-general. In that year he returned to active service as chief of staff to his old friend and mentor, Field Marshal Graf August von Gneisenau, who was commanding the army mobilized to secure Prussia’s border with the Russian-dominated Kingdom of Poland, where a revolt and cholera epidemic had broken out. Both men died of the disease, Clausewitz on 17 December 1831. He was fifty-one.

The Genesis of On War

From an early age Carl von Clausewitz exhibited a deep interest in political and military history. His major works, including On War, were written after 1815 but even during the wars he was a prolific essayist and contributor to military periodicals. Clausewitz came to believe that history was the key to theory; thus the fusion of the historical and the theoretical in his writings. His studies of the campaigns of the Revolutionary/Napoleonic and earlier wars provided the raw materials for his theoretical works. Having borne personal witness to many of those campaigns and battles, he was able to write about them with the authority of a scholar who was also a veteran soldier.

The trend in Clausewitz’s writing about war was toward critical analysis: He sought to develop a definition of war as a social phenomenon—one that would be applicable to all wars, past, present and future. This mode of analysis comes out most clearly in his magus opus, On War, probably the most influential study of the subject every written.

The Ideal and the Actual in On War

Clausewitz is often described as the apostle or prophet of total war, a view based on a misunderstanding of his mode of analysis. In the first chapter of On War he announces:

I shall not begin by formulating a crude, journalistic definition of war but will go straight to the heart of the matter, to the duel. War is nothing but a duel on a larger scale. Countless duels go to make up a war but a picture of it as a whole can be formed by imagining a pair of wrestlers. Each tries through physical force to compel the other to do his will; his immediate aim is to throw his opponent in order to make him incapable of further resistance.

War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.

But this definition is only the starting point of Clausewitz’s analysis and he then goes on to work out its implications. The first of these is that war being an act of force, there can no logical limit to the application of that force. The second is that the immediate aim of war must be to disarm the enemy. The third is that both sides will make a maximum effort. Clausewitz argues that these things must be so because war is a clash of two living wills that sets in motion a series of reciprocal actions with extreme outcomes. If one side ratchets up the level of force, the other side must follow suit—the first extreme. Since each side seeks to disarm the other, both sides are driven to a second extreme. If one side increases the intensity of its effort, the other side must follow suit—the third extreme.

Together, the initial definition and the three extremes constitute Clausewitz's definition of ideal war.

From this definition alone it might be supposed that Clausewitz is indeed advocating total war on all occasions. By no means. Having framed it he goes on to say: “But move from the abstract to the real world, and the whole thing looks quite different.” Indeed it does, and this is the starting line from which the author advances upon his well-known though frequently misunderstood conclusion: “It is clear, consequently, that war is not a mere act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political activity by other means.” And it follows that the political objective of a given war—a thing external to war itself—will determine the character and course of every war.

The point Clausewitz makes is a subtle one. Note that he characterizes war not as an "act of policy" but as "a true political instrument." The political objective, Clausewitz argues, must always serve as the template for military strategy. If that objective is a limited one the war will, or ought to be, similarly limited. And it is the task of the political leadership to make policy; the task of the soldiers is to carry out that policy by force. This is far indeed from the popular notion that once war breaks out, the politicians should step back and let the military get on with it. It may well be true that as a war progresses, policy evolves. But even so the principle holds good: War is instrumental, policy is fundamental.

Elaboration of the Actual

What, then, is the value of Clausewitz’s theoretical concept, ideal war?

Ideal war is best described as an analytical tool. While it’s true in a general sense that actual war, being an instrument of policy, takes its character from that policy, many things happen in the course of war that can’t be explained in that way. Why, for example, are military campaigns characterized by frequent periods of inaction? If one side is compelled for some reason to pause, ought not the other side take action? The reciprocal extremes embodied in ideal war would seem to suggest so; indeed, they imply a principle of polarity. Whatever benefits A should penalize B, and vice versa. Why, then, does polarity not operate on all occasions? The answer, says Clausewitz, is that war consists of two forms of fighting, attack and defense, and that defense is much the stronger form of war. Thus if it benefits A to attack B immediately, it benefits B to be attacked at some later time. But in no way does it follow that B should launch an immediate attack on A—for that would require an entirely fresh set of calculations.

By using the concept of the ideal in this way, Clausewitz reveals the true character of war. The ideal conception says that certain things should be happening in a given situation. So why aren’t they? There turn out to be many reasons, some of which Clausewitz calls frictions: the sand in the gears of the military machine. Bad weather, inaccurate maps, fatigue, misleading intelligence reports, messages misunderstood or misdirected—all these things and more conspire to prevent actual war from approaching the ideal.

Frictions aside, war is also the preserve of uncertainty and danger. A commander can never be one hundred percent certain of the enemy’s strength, morale and intentions. Added to this uncertainty is consciousness of the danger inherent in any decision, whether to attack, to await an attack, to shift one’s position, and so on. Thus for the commander, war is very much a matter of assessing probabilities, sheer guesswork, and luck.

Clausewitz concludes that actual war, ruled by frictions, uncertainties and the consciousness of danger, resembles nothing so much as a game of chance, an insight that introduces his discussion of “Genius in War”; that is, the intellectual and moral (psychological) characteristics of a great commander. His own experience had taught Clausewitz that the human factor is central to an understanding of war, and in On War he discusses such issues as military morale, the corporate personality of the army, courage, boldness, fear, etc.

Clausewitz summarizes his analysis of actual war in a famous passage, calling it “a fascinating trinity—composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which are to be regarded as a blind natural force; the play of chance and probability, within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to pure reason.”

The Enduring Relevance of On War

At the time of Clausewitz’s death he regarded only the first chapter of Book One of On War as a finished product; the rest he characterized as a “formless mass” that required extensive revisions. This doubtless accounts for some of the contradictions that readers of On War have noted. His more thoughtful critics through the years have focused on Clausewitz’s obsession, as they see it, with decisive battle. He certainly did assert that war necessarily involves fighting and that the commander should always strive to bring about a decisive engagement. The great aim of military strategy, he held, is to concentrate maximum power at the decisive point—an aim that seemingly contradicts his principle of political primacy in war.

On War has also been criticized on general grounds of relevance. Clausewitz’s personal experience and historical knowledge embraced the wars of the Revolutionary/Napoleonic era and those of earlier times, especially the wars of Frederick the Great. But do those wars, fought with muskets and bayonets, muzzle-loading cannons, swords and sabers, have anything to teach us today? In some ways, of course, they don’t but in other ways, even leaving On War aside, they do. When Frederick the Great wrote that “The best way of achieving victory is to march briskly and in good order against the enemy, always endeavoring to gain ground,” he was articulating a timeless principle of war: Seize the initiative and exploit it. And when a recent study of the US military involvement in Afghanistan concluded that there had never been a settled policy or military objective governing the conduct of that war, what thoughtful reader could have failed to reflect with Clausewitz that “The first, the supreme, the most far-reaching act of judgment that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish…the kind of war on which they are embarking.”

Clausewitz did not write a how-to book. Unlike Sun Tzu, Napoleon or Antoine-Henri Jomini he does not pronounce military maxims or prescribe stereotypical rules of conduct for the commander. Instead he seeks to penetrate to the heart of the matter, to see war as it really is, and to separate those elements of it that are timeless from those that are transitory. His success in that endeavor has assured the continuing relevance of On War.

Bibliographical Note

The primary source is, of course, On War itself, a challenging but rewarding study. The best edition in English was translated and edited by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (1976). It includes illuminating introductory essays, and a guide to reading On War by Bernard Brodie.

There have been numerous biographies of Clausewitz, prominent among them Peter Paret's Clausewitz and the State: The Man, His Theories, and His Times (revised edition, 1985). Paret's is an intellectual biography that places Clausewitz and On War in their historical context.

Clausewitz was a Prussian, and an understanding of the man and his work depends on an understanding of the environment and institutions—political, social, cultural—that shaped his personality and informed his thought. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947 by Christopher Clark (2006) is a full-dress history of Prussia from the sixteenth century to modern times.

Clausewitz was also a product of the Prussian Army, on which he left a lasting imprint. Walter Goerlitz's History of the German General Staff 1657-1945 traces out these Clausewitzian influences in a study of the Prussian, later the German, Army's key institution and intellectual center.