Though the Commentary Magazine Podcast is on hiatus this week, John Podhoretz and the gang prerecorded some non-political tidbits to fill the gap. Yesterday’s offering: "Our Favorite Science Fiction.”

Matthew Continetti led off with the pertinent observation that in its Golden Age, SF was the province of the short story. Back when future masters of the genre like Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein were starting out, the pulp magazines made it possible to earn a living by writing short stories. They paid a penny or two a word, which encouraged a high rate of production and guaranteed that plenty of dreck would see print. But even so, between the Forties and the Seventies, much classic SF was produced. And reviewing my own list of SF favorites, I found that the majority of them were indeed short stories.

Their titles might be familiar to fans of SF who, like me, are now collecting Social Security. But readers under forty may not, perhaps, have had the pleasure of reading these classics. Here then, presented in no order of preference, are the ten SF short stories that first came to mind when I started thinking about my favorites.

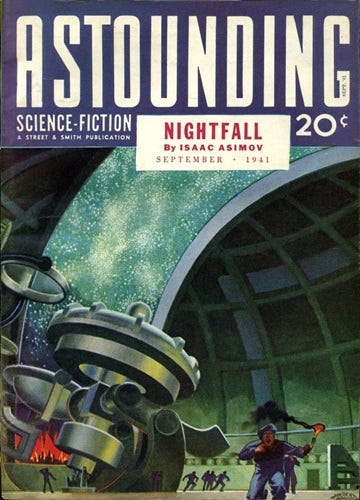

“Nightfall” by Isaac Asimov (Astounding Science Fiction, September 1941). The Good Doctor was known to complain about being told that this brilliant story, produced in the early days of his career, was the greatest thing he’d ever written. What, had it been all downhill from there? Clearly not: the Foundation stories, the robot stories, and many more were yet to come. But this tale, inspired by a quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson, established him as one of the top writers of SF’s Golden Age. “If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore, and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God!” Emerson wondered. Asimov talked it over with Astounding’s editor, John W. Campbell, and “Nightfall” was the result.

“Billennium” by J.G. Ballard (New Worlds Magazine, November 1961). The science fiction horror story subgenre includes some memorable classics: John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” Damon Knight’s “To Serve Man,” Philip K. Dick’s “Colony,” But despite its quiet, almost offhand manner, nothing beats this chilling tale set in a radically overpopulated near future society where space, to put it mildly, is at a premium. Ballard was a writer whose output ranged from quirky to transgressive, and the quality of his work was variable. Some of his stories fall flat; a few are just plain bad. Not this one, however, whose final passage is like a cold finger, drawn slowly down your spine.

“Fondly Fahrenheit” by Alfred Bester (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, August 1954). From the day of its publication, this tale of a man and his murderous android servant has been hailed as a dazzling tour de force. Robert Silverberg, himself no slouch, called it a "paragon of story construction and exuberant style”—as indeed it is. Bester, who also worked as a TV, radio, and comic book scriptwriter and magazine editor, was an unequalled master of plot, pacing, and language: “He doesn’t know which of us I am these days, but they know one truth.” With this perfectly wrought sentence, Bester leads us into the labyrinth of a deadly personality disorder.

“A Subway Named Mobius” by A.J. Deutsch (Astounding Science Fiction, December 1950). Armin Joseph Deutsch was a distinguished American astronomer who published exactly one SF short story. But what a story it is! And the story behind it is just as good. In 1950, Isaac Asimov was teaching biochemistry at the Boston University School of Medicine, and Deutsch was teaching astronomy at Harvard. The two got to know one another, and one day Deutsch called Asimov to ask if he could read him the first few paragraphs of an SF short story he was writing. Asimov remembered that he groaned inwardly. “Still, one must be polite.” So Deutsch began and as he listened, Asimov grew more and more excited. He told Deutsch that he should submit the story to John W. Campbell at Astounding. He did and Campbell bought it. This tale of a Boston subway train that vanishes into the fourth dimension is a marvel, and it’s a shame that Deutsch, who died in 1969 at the age of fifty-one, never wrote another.

“Second Variety” by Philip K. Dick (Space Science Fiction, May 1953). Today, Philip K. Dick is best known for his alternate history novel, The Man in the High Castle (1962), which was made into an Amazon Prime TV series. Earlier in his career, however, he produced some noteable short stories, including this mordant postapocalyptic tale. A nuclear war between the superpowers has laid waste to the surface of the Earth. The North American/UN government has relocated to a base on the Moon, leaving its surviving troops behind to carry on the fight against the Soviets. A new weapon is deployed against the enemy: miniature robots equipped with razor-sharp blades, programmed to attack any warm body not protected by a special radioactive wristband. Produced in automated underground factories, operating independently, these claws as they’re nicknamed turn the tide of the war. But victory turns out to be anything but sweet.

“Solution Unsatisfactory” by Robert A. Heinlein (Astounding Science Fiction, November 1940). Science fiction is not really in the business of prediction. Very often, indeed, it misses the mark on that score. But sometimes a writer hits the nail on the head, as Robert A. Heinlein did with this remarkably prescient story. Before America had even entered World War Two, he forecast the development of atomic weapons, predicted that they would be used to end the war, and anticipated the subsequent Cold War with its balance of terror. Heinlein didn’t get every detail right, of course. The atomic weapon in the story was not an explosive but a deadly radioactive dust that could be delivered by aircraft. And the postwar world he described was much grimmer than the reality. Even so, this tale is a classic of SF prediction, served up with the author’s characteristic panache.

“The Little Black Bag” by C.M. Kornbluth (Astounding Science Fiction, July 1950). If his novels and stories are anything to go by, C.M. Kornbluth had no very high opinion of human nature. But as this brilliantly plotted and paced story shows, that touch of misanthropy served him well as a writer. A medical bag, accidentally sent through time from the future (and it’s some future), finds its way into the hands of an alcoholic former physician, now living on Skid Row. The little black bag of miracles rehabilitates old Dr. Fell, and readers may think that they know where the story is headed, but Kornbluth has a brutal reality check on his agenda.

“The Snowball Effect” by Katherine MacLean (Galaxy Science Fiction, September 1952). For his Foundation story cycle, Isaac Asimov invented “psychohistory,” a branch of mathematics capable of charting the course of future history. In this tart and amusing tale, Katherine MacLean does something similar: A university president challenges the chairman of his sociology department to conduct a demonstration of sociology’s practical applications. The chairman creates a mathematically generated template for optimal organizational growth, and together they apply it to a real-world organization: the Watashaw Sewing Circle. And the rest is history—a future history that neither the president nor the chairman had bargained for.

“The Screwfly Solution” by Raccoona Sheldon. (Analog Science Fiction and Fact, June 1977). Raccoona Sheldon was one of several pen names used by Alice Sheldon, the best-known of which was James Tiptree, Jr. Sheldon was a psychologist by profession, and as a writer she was preoccupied with questions of gender. Both influences are evident in this chilling tale of a worldwide epidemic of murderous misogyny that evolves into a genocidal campaign by men against women. The Handmaid’s Tale is cheery by comparison, and the story ends with a twist of the knife that rivals the last sentence of “To Serve Man.”

“Born with the Dead” by Robert Silverberg (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, April 1974). Though this one by the prolific Robert Silverberg is a novella rather than a short story, it definitely belongs on this list. In the near future a method of restoring life to the dead has been perfected, and people may choose to be rekindled, as the process is called. But the resurrected dead are strangely detached from their former lives. They prefer to live apart from the rest of humanity in “Cold Towns,” and have evolved a culture whose details are shrouded in secrecy. Silverberg depicts this world through the eyes of a bereaved husband, desperately striving to reconnect with his rekindled wife, who is no longer the woman he loved. This sad and remarkable story of love and estrangement will stick with you.

Just cause I felt the need, I thought I would add a few more :-)

How about "The Last Question" by Isaac Asimov, first published in November 1956 issue of Science Fiction Quarterly. I think I read it first in his Bicentennial Man anthology. I actually think it's better than Nightfall.

First published through serialization in 1928 in Amazing Stories, The Skylark of Space by E. E. "Doc" Smith. Technically not a short story, but each serial chapter was a self-contained story. It's the very first Space Opera and one of my all time favorites.

In fact, a lot of SF that we think of as novel length started off as serials in Amazing Stories.

Just emailed this to myself!