Over at National Review Online, Jay Nordlinger has asked readers to tell him what book or books most influenced their intellectual development and political outlook. For me, the answer to his question came instantly to mind: the works of George Orwell.

Orwell and I were contemporaries, if just barely: I was born on August 16, 1949, and he died on January 21, 1950, at the age of forty-six. But though we never met in person, I did get to know him, our acquaintance dating from the early Sixties.

Orwell’s best-known books, Animal Farm (1946) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) were bestsellers in both Britain and America; the latter was a Book of the Month Club main selection. Because my father was a prodigious reader, both books were to be found in our house—and find them I did at the age of thirteen or fourteen, shelved in the basement among forgotten bestsellers of the Fifties. I read Animal Farm first and enjoyed it, though most of the historical background was over my head. But Nineteen Eighty-Four made an immediate and profound impression on me. Growing up in the long shadow cast by the age of totalitarianism and the Second World War, I could perceive something at least of what the author was driving at.

That’s the first facet of Orwell’s influence on me: It was from him that I received a first dim inkling that literature existed for a purpose higher than entertaining me.

A little later I became acquainted with Orwell as an essayist, a journalist and a pamphleteer. In the English literature anthologies used in schools back then, “Shooting an Elephant” was usually to be found, and I recall reading it as a high-school senior. Some time later I acquired a paperback collection of Orwell’s essays that included “A Hanging,” “Rudyard Kipling,” “Boys’ Weeklies,” “The Art of Donald McGill,” and others. In college after four years of military service I delved deeper into Orwell, and today I can fairly claim to have read all his major works, and a considerable portion of his minor ones as well.

But to characterize any piece by Orwell as minor seems wrong. Even in book reviews and newspaper articles the care that he devoted to his writing is obvious. He was a master of the first line: “Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent” (“Reflections on Gandhi,” 1949); “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen” (Nineteen Eighty-Four). That line of fourteen words abruptly transports the reader from the world of the familiar to Orwell’s sinister alternate reality. Shrewdly, however, he situated his dystopia on familiar terrain: bare, dilapidated, bomb-scarred, wartime London—a setting instantly recognizable to British people of the early postwar era. For its first readers, the novel derived much of its terrifying power from that amalgam of mundane reality and visionary nightmare.

That’s the second facet of Orwell’s influence on me: He was my most important writing teacher.

As a politically engaged writer, George Orwell was a man outside the system: an intellectual without a university degree, a professed socialist but not a party man, a patriot with no illusions about John Bull. In him were combined left-wing convictions and a conservative temperament. Orwell was both an internationalist and a Little Englander. He believed in a socialist future but regretted the passing of the Edwardian age into which he was born. He was an avowed atheist who desired his funeral to be conducted according to the Anglican rite and who wished to be buried in a churchyard. These contradictions with their touch of doublethink served him well. They endowed him with a certain independence of outlook, such that he could include in The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) a positively scathing criticism of socialists: “As with the Christian religion,” Orwell wrote, “the worst advertisement for Socialism is its adherents.” This sentence and the argument derived from it have echoed down the years, and there are those on the contemporary Left who still feel and resent the sting of Orwell’s critique.

He was not a party man or an ideologue; Orwell seemed naturally immune to groupthink and the lure of the dialectic. For him, socialism was simply a genius of the manifest. As he wrote in The Road to Wigan Pier, “Socialism is such elementary common sense that I am sometimes amazed that it has not established itself already.” Of course it isn’t at all elementary—as perhaps he was coming to realize toward the end of his life. Orwell wasn’t always right. But there is this to be said for him, that he strove for intellectual honesty. “No case is really answered until it has had a fair hearing,” he reminds us in The Road to Wigan Pier. To the disregard of that principle may be traced much of what’s wrong with contemporary politics in the democratic West.

That’s the third facet of my debt to Mr. Orwell: He modeled for me the value of constructive skepticism, the proper uses of the awkward question, the high value of being honest with one’s self as well as others.

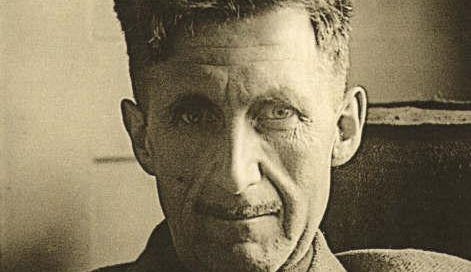

In his book Why Orwell Matters, the late Christopher Hitchens complained that George Orwell has been made into a secular saint. This is no doubt true—though the man himself would have rejected, indeed deplored, the title. But photographs of him taken in his last years are evocative of sainthood, or at least of martyrdom. John Morris, one of his wartime BBC colleagues, recalled Orwell’s “curiously crucified expression,” which no doubt contributed toward his posthumous canonization. So too does his reputation as a political prophet.

The Left and the Right alike lay claim to George Orwell’s legacy, and each side argues a plausible case. Whatever his idiosyncrasies, Orwell was certainly a man of the Left. On the other hand, by his analysis of totalitarianism he became one of the founding fathers of postwar anticommunism. Animal Farm satirized the Bolshevik Revolution and Stalinism; Nineteen Eighty-Four satirized totalitarianism more generally. But though it seems doubtful that Orwell intended the latter book as a prophetic vision of the future, with the passage of time Nineteen Eighty-Four has acquired an aura of genuine prophecy—the monstrous North Korean regime being the example most often cited. But the radical relativism that Orwell portrayed via Oceania, Ingsoc, Newspeak, doublethink, the systematic alteration of the past, the cult of the all-pervasive Leader, infects our own politics as well. Take, for instance, the ongoing campaign to decouple “gender” from human biology. Are not such words and terms as birthing person, pansexual, gender fluid, etc. examples of Newspeak, intended to align our speech and thought with the tenants of gender ideology?

George Orwell didn’t convert me to socialism; too much had already happened between his death and my coming of age for that to be possible. But he did teach me to notice when politicians, intellectuals and journalists play games with history, with language and with reality itself. That’s the fourth facet of my debt to Mr. Orwell, a debt that I gratefully acknowledge and can never repay.

The Jungle by Upton Sinclair is a book that caught my attention. I read it as a kid living in Chicago where my father worked as a boilermaker.

I knew intimately from watching my father and hearing his stories about how brutal life was for working class men and women in those days. Raw and harsh ~ and that was after working people (many socialists or union types) had struggled for basic concessions.

Needless to say, as a young boy, I was probably a socialists in spirit, without really understanding it. It wasn’t ideology. It was simple recognition of reality. I’m sure that’s what oriented Orwell given his time in the world and his experiences.

Some socialism is good. Too much is definitely bad. And too much ideology in anything is a recipe for disaster.

I say that now as a conservative older man.

Most people on the left today have no real experience with such realities. Instead, it’s mostly a kind of fetish for wealthy and over educated types to wallow in their (current thing) “compassion” and to project their “virtues” amongst their own. That and a giant grift and opportunity to seize power within the institutions in the name of preferred (client groups) who often are facing real oppression.

But little progress comes of it. Millions are spent, while the actual poor remain unaddressed. Instead, funding for the nonprofits and NGOs rolls on, serving only to build resumes and more power for the elect.

Meantime, the actual working class (and less) are demonized for caring about the boarder, crime, and drugs and for not saying the right words or holding the correct opinions about the “rights” of men to get undressed in the lady’s room or to beat the shit out of girls on the basketball court.

Does that sound like fucking progress?

The value of a system should be measured by what it actually does. Not bullshit words.

In any case, thanks Andrew Carnegie for the opportunity to read that book. 😉

Orwell is so often cited as a prescient social/political essayist, it's easy to lose sight of how good a writer of prose he was. I had occasion to mention him in an essay on tone of voice recently:

Orwell does a similar thing in 1984. The Party’s three slogans—War is Peace, Freedom Is Slavery, Ignorance is Strength—help to establish a world where familiar values are turned upside down. Thus, Orwell can invoke a father’s pride in his children with devastating effect:

“Did I ever tell you, old boy,” he said, chuckling round the stem of his pipe, “about the time when those two nippers of mine set fire to the old market-woman’s skirt because they saw her wrapping up sausages in a poster of B.B. [Big Brother]? Sneaked up behind her and set fire to it with a box of matches. Burned her quite badly, I believe. Little beggars, eh? But keen as mustard!

When I think of Orwell, the first thing that pops into my head--oddly, perhaps--is DOWN AND OUT IN PARIS AND LONDON, especially his intimate portrait of life in the "back of the house" of a Paris eatery--or, truly, the underneath of the house; it was my first exposure to the word plongeur, which has found a home in my psyche for what reason I do not know.

Anyway, I just subscribed to your posting. I know we'll disagree at times, for which I'm grateful.