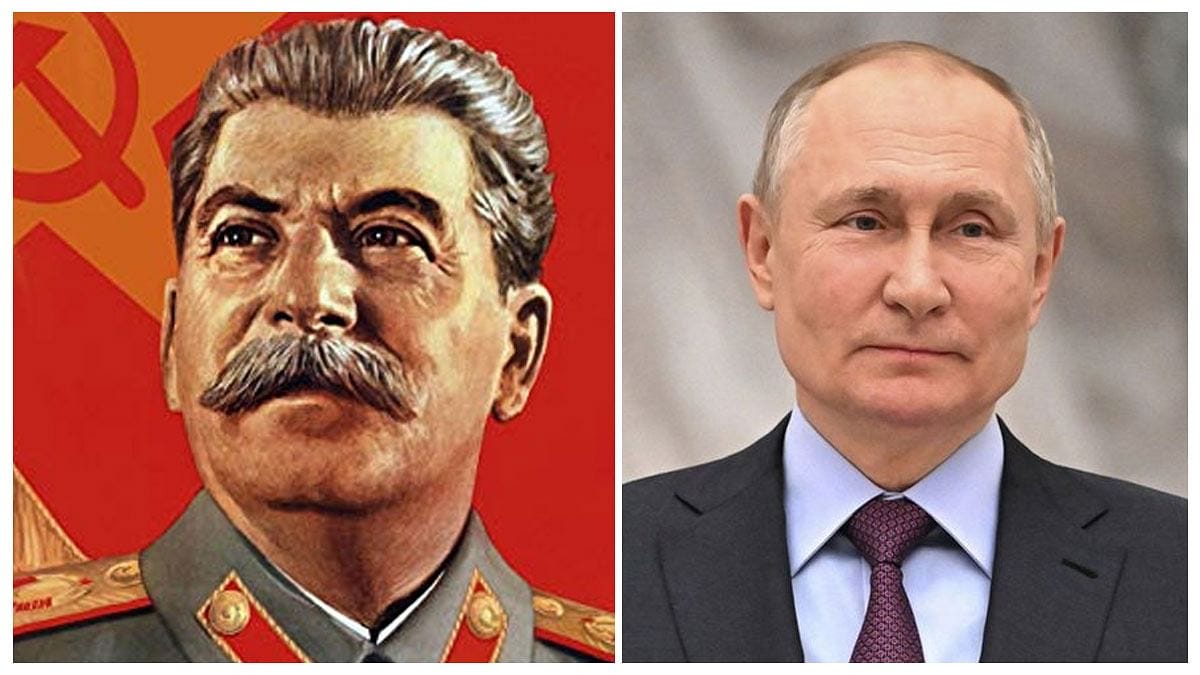

Stalin and Putin and Ukraine

Tracing the connections between two genocidal crimes, one past, one present

Note: This seems an opportune moment to remind V. Putin’s American and European fanboys and -girls just why the president and people of Ukraine are disinclined to accept the subjugation of their country to Russia for the sake of “peace” and Donald Trump’s inflated ego.

Everybody knows about the Holocaust, the standard of the twentieth-century genocide industry, but the Ukrainian terror-famine—the Holodomor (murder by starvation) as Ukrainians call it—is much less well known. But in its horror, the latter rivals the former: An estimated four million Ukrainians, most of them peasants, died in 1931-33, the victims of deliberate state policy.

The story of the Holodomor has been well told, first by Robert Conquest in The Harvest of Sorrow (1986), and more recently by Anne Applebaum in Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine. It’s a story of particular relevance at the present moment, when Stalin’s would-be heir, V. Putin, is making his own bid to destroy Ukraine as an independent country and eradicate the Ukrainian national identity.

This fearful crime against humanity came about because the Bolshevik leadership of the Soviet Union, fearing and distrusting the independent peasantry, anxious to get control over the nation’s food supply, resolved to collectivize Soviet agriculture. In plain language, they decided to re-enserf the peasants by taking away their land and property, turning them into laborers on state-controlled farms. Various carrots and sticks were applied to this end, and when none of them worked Stalin and his henchmen resorted to coercion by starvation.

The background to the Holodomor was as follows. In 1928 the Soviet Union had launched the First Five-Year Plan, a grandiose industrialization drive intended to lay the foundations for a true worker’s state and transform the country into a world power. The technology—machine tools and the like—necessary to create heavy industry would have to be purchased abroad and for this hard currency was required. And the obvious way for the USSR to accumulate that hard currency was to export grain for sale abroad.

But the central government did not control the national grain supply. After the Revolution, the peasantry had come into possession of the land, which they held either collectively through the institution of the Russian village commune or as individual owners. The peasants also became the owners of the land’s produce, principally grain. What they did not consume themselves they sold in exchange for manufactured products and other necessities. In the eyes of the Bolsheviks, this was a form of capitalism that deprived the socialist state of its due while sowing the seeds of counterrevolution.

Socialism had always had a vexed relationship with the peasantry. Founded as it was on the exaltation of the proletariat—supposedly the class destined to lead humanity into the radiant future—socialism regarded the peasantry with dislike and suspicion—this thanks to the peasant’s innate conservatism, religiosity and primitive nationalism. Marx wrote of “the idiocy of rural life,” dismissing the peasant as a clod devoid of political consciousness. In vague terms he described a socialist future in which the distinction between town and country would be erased, with agricultural production organized along industrial lines. The peasant would thus become a proletarian.

So the Bolsheviks’ decision to collectivize Soviet agriculture merely fleshed out Marx’s vision. And their ideologically inherited dislike and suspicion of the peasantry was honed to a fine edge of hatred and rage by the practical necessities, as they saw them, of industrial development.

The terror famine had two objectives: to obtain grain by confiscating it from the peasants and to force them onto the collective farms. The first attempt to collectivize agriculture in 1929-30, brutal as it was, failed in the face of peasant resistance, both passive and violent. Stalin thereupon resolved on measures even more drastic than those hitherto employed. All grain, all foodstuffs, were now to be confiscated— essentially at gunpoint. Grain collection “brigades” backed by the police and the Red Army were sent into the countryside, and they stripped the peasantry naked. In many cases this was no figure of speech: peasants were evicted from their houses, sent naked into the street. The brigades took everything: the family cow, pigs and chickens, clothing, furniture, cooking utensils, knives, forks and spoons, bedding, religious icons, the smallest personal items. Most fatally they took the peasants’ seed grain, making it impossible for a new crop to be sown.

Many peasants were summarily executed or deported to the Gulag for the “crime” of withholding grain from the authorities. Women caught gleaning harvested fields for a few grains of wheat were shot. As food supplies disappeared desperate people ate their pets, they ate flowers and grass, they ground acorns to make ersatz flour, they foraged in wooded areas for wild mushrooms and berries, they boiled shoes and belts and ate them, they made soup from river weeds. And finally, as the village houses filled up with corpses, some ate the dead.

Everywhere there was hunger, nakedness, disease, madness, death. Finding no food in the countryside, people fled to the cities and starved there. Squads of workers patrolled the streets in trucks, picking up the corpses of those who’d died overnight. Most were simply dumped in pits and bulldozed under, no effort being made to identify the dead or record the location of the site. The famine created orphans by the tens and hundreds of thousands. State orphanages filled up and overflowed, so schools were closed and the buildings used to house children found wandering in the streets. But there was little or no food, no medicine, no blankets, no running water, and the children too died in droves.

In the midst of these horrors, human reactions varied: shocking acts of inhumanity and cruelty here, noble acts of charity and self-sacrifice there. One Western visitor to the Ukrainian countryside mused that if Dante could see what was happening, he would feel compelled to revise his Inferno.

Though the policy of coercion by starvation affected other areas of the Soviet Union, it was applied with particular savagery against Ukraine. As one of the Soviet Union’s most important grain-producing regions it was naturally a focus of the collectivization drive. But there was more. Ukraine harbored a national consciousness: it had its own language and culture. What was worse from the Bolsheviks’ point of view, it had numerous connections with the West. Eastern Poland was home to many ethnic Ukrainians; a large part of Ukraine had once belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. At the end of the Great War Ukraine had declared independence from Russia, though it proved unable to maintain that status. Even so, in the early days of the Soviet Union, Ukrainian nationalism had briefly flourished. But it soon came to be seen as an existential danger to the state. Like Putin & Co. today, the Bolsheviks believed that only with Ukraine could Russia call itself as a great power. Therefore, all aspects of the Ukrainian national identity had to be stamped out.

And so in Ukraine, the terror famine had the additional objective of destroying for all time the Ukrainian national idea. It was no coincidence that on the heels of the Holodomor, what remained of the Ukrainian intelligentsia was liquidated in a vicious purge, supplemented by a campaign to suppress Ukrainian culture and even the Ukrainian language.

Robert Conquest’s The Harvest of Sorrow was the first full-scale history of the terror famine to be published—a searing and pioneering account. But with the sources available to him at the time, many of Conquest’s conclusions were tentative. Since the fall of the Soviet Union much more information has come to light, and Anne Applebaum’s Red Famine confirms what Conquest could only suspect: that the 1931-33 famine was a deliberate act of mass murder, carried out by the Soviet leadership against the Soviet people in pursuit of political and economic objectives—with a special, monstrous emphasis on Ukraine.

A notable feature of the terror famine was the conspiracy of silence that long surrounded it. It was natural enough for the Soviet government to cover up the facts, for example by fiddling with census figures to hide the staggering death toll: around six million in all. During the Great Purge (1936-38) many census experts were liquidated for just that reason. Less understandable, because morally outrageous, was the reaction of the Western Left. At the time of the famine, news about its horrors trickled out, to be reported in the Western press. These stories were denounced by socialists in Europe and America as provocations and lies designed to sully the image of the world capital of socialism.

Most notoriously, the New York Times’ correspondent in the Soviet Union, Walter Duranty, connived with the Soviet government to suppress the facts. In return for various privileges—a large, well-appointed apartment, a car, special access to Soviet officials, personal interviews with Stalin, even a mistress—he filed stories from Moscow denying that famine conditions existed in the Soviet Union. In 1935 he had the audacity to write that though some people had suffered, “the suffering is inflicted with a noble purpose.” There can be no doubt that Duranty knew what was really happening but to the American public he reported fake news, in the process becoming one of the world’s most influential journalists. For his series of articles on the success (!) of the Soviet collectivization drive Duranty was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1932. It has never been revoked.

Something similar is happening today among those groups, Left and Right, who oppose American-led efforts to support the Ukrainian government and people in their resistance to Putin’s vicious war of conquest. Either they say that no US national interests are at stake in the Russo-Ukrainian War or they assert that Putin has some justification for his actions. One complaint often heard from these precincts is that the Ukrainian government is “corrupt” and therefore unworthy of support—as if that excuses Russian war crimes. Another is that Putin is merely reacting to “NATO aggression.” Or we’re told that the Russians are waging a war of liberation to rescue ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine from the oppressive rule of a foreign power—a rather hilarious claim given the fact that Putin and his cabal have made no bones about their actual objective.

What these isolationists and appeasers never mention is the historical background sketched above—which explains why the Ukrainian people have so fiercely resisted the invader. They remember the Holodomor and they know that V. Putin is reprising the policy of J.V. Stalin. For Ukrainians, the war now raging is a battle for survival. And the prevention of genocide is most assuredly in the American national interest, because a world in which such things are permitted to happen would be a dangerous world indeed—not least for America.

I probably should have mentioned that this article was originally published in August 2022.

An excellent article, Mr. Gregg that not only recounts some very important history that is too little known but also a clarion call for why the United States must ensure an honorable peace for both sides and stand with Ukraine! Russia is no stranger to committing genocide. As the Soviet Union, the murdered around 3.5 to 5 million Ukrainians during the Holodomor. Intentionally starving millions of men, women and children to death in the name of building the prefect world as they saw it. Now as the Russian Federation they have done it again. Russia has committed war crimes in Ukraine the likes of which haven’t been seen on the continent since the days of the Yugoslavian Civil War of the 1990s. Mass murder, mass rape, kidnapping children, bombing hospitals, blowing up apartment buildings full of people, germ warfare, fighting alongside Neo-Nazis in the Wagner Group, shooting stray dogs for the h*** of it, using ethnic minority soldiers and volunteers from Latin America, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa as cannon fodder, firing missiles at apartment buildings in broad daylight, carpet bombing urban areas, etc., etc. the list is endless. This war is to be sure, a bloody stalemate no one can win. But that doesn’t mean Putin should be able to sign a peace deal that’s basically a give away to him with no terms or conditions. Nor should Ukraine walk away with nothing. Russia is still despite their disastrous performance in the war, a major threat to all of Europe and the world. In negotiating this peace agreement we must ensure Ukraine comes out of this okay. Their security must be guaranteed one way or another, money must be set aside to help rebuild the country and Ukrainian refugees must be given assistance. In addition, the United States must send humanitarian aid to Ukraine. We must not abandon our staunch allies. The nations of Europe need to also do something that’s long overdue: increase defense spending and increase the size of their militaries.