Prelude to Pointblank

Part Six • Early Operations of the US Eighth Air Force 1942

The US Eighth Air Force commenced operations in the summer of 1942, and during the year that followed the stage was set for Operation POINTBLANK: the Combined Bomber Offensive that would crush the Luftwaffe and devastate urban Germany. For RAF Bomber Command, the prelude to Pointblank was a period of consolidation. Though large raids continued to be launched, the command’s operational tempo slowed somewhat as new aircraft were introduced, lessons were digested, and tactics were refined. But for the Americans, it was a baptism of fire and an opportunity to show that the concept of daylight precision bombing was viable.

The very first combat mission to be conducted by Eighth Air Force was largely symbolic—as its date, 4 July 1942, indicated. The mission was flown by the 15th Bombardment Squadron (Light) (Separate), whose personnel had arrived in Britain without their own aircraft. For the Fourth of July mission, the 15th borrowed a number of RAF Boston light bombers, these being the Lend-Lease version of the A-20 light bomber with which the squadron was intended to be equipped. The RAF provided the necessary training to the 15th’s combat crews, six of which were selected to join six RAF Bostons in a low-level attack against German airfields in Holland.

Tactically, this first Eighth Air Force mission was nothing to boast about. Only two of the American Bostons bombed their assigned targets, two others were shot down by flak (antiaircraft fire), and another was badly damaged. But there was one notable incident. The Boston piloted by Captain Charles Kegelman was hit by flak that damaged its right engine and wing, lost altitude, and actually struck the ground. But the bomber bounced back up and Kegelman managed to keep it in the air. Then, as he turned for home, the guns of a German flak tower opened fire on his plane. Kegelman turned, flew toward the tower, and shot it up with his nose guns. The German gunners ceased fire and dived for cover. Kegelman then brought his damaged Boston back to base, flying at wave-hopping altitude across the English Channel. He was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. The 15th flew another combat mission on 12 July, this time attacking at medium altitude with no losses. Shortly thereafter the squadron’s A-20s arrived from the United States and the 15th spent the next few weeks making them operational.

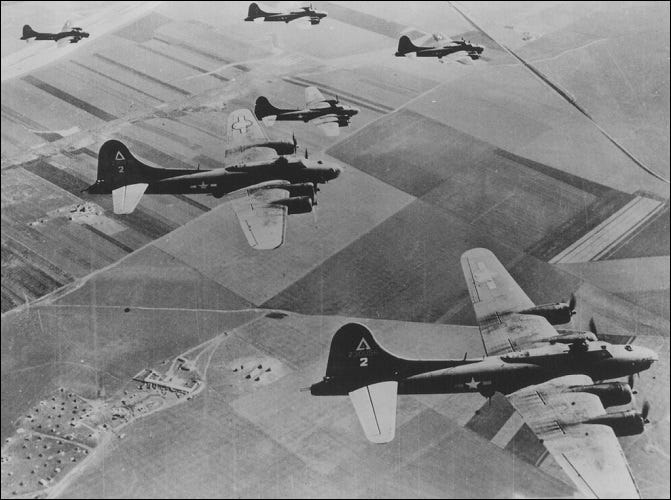

So the Americans entered the battle—if only symbolically— as meanwhile the combat crews of the 97th Bombardment Group (Heavy) completed their training. By 15 August twenty-five crews were declared ready for daylight bombing missions. The commitment of these crews and their B-17s would mark the real beginning of the American daylight bombing offensive and it only remained to select a suitable target. At this early stage an attack deep into Germany itself was obviously out of the question; the target would have to be within the range of fighter escort. The choice fell on the Sotteville railroad marshaling yard at Rouen in Normandy, an important transportation hub. The attack would be delivered by twelve B-17s in two six-plane flights, with another six flying a diversionary mission off the coast. Nine Spitfire squadrons of RAF Fighter Command would provide the fighter escort. The attack was scheduled for 17 August, aircraft to begin taking off from Grafton Underwood at 1530 hours. Major General Ira Eaker, now commanding VIII Bomber Command, would ride along in Yankee Doodle, lead bomber of the second flight.

Though small in scale, the Rouen-Sotteville mission generated considerable attention, great excitement, and not a little anxiety. For the 97th Bombardment Group, it marked the end of a long and tedious period of training. For the American commanders, Major General Eaker and Major General Carl Spaatz, commanding the Eighth Air Force, it was the moment when their theory of daylight precision bombing would be put to the test. Numerous senior officers, British and American, including General Eisenhower himself, were present to see off the 97th on 17 July, along with a large contingent of journalists.

The plan called for the B-17s to bomb from an altitude of 23,000 feet. Visibility over the target was good and all twelve B-17s were able to attack, dropping a total of 36,900 pounds of high-explosive bombs—about half of which hit the general target area. This was considered good for a first effort and even those bombs that missed the designated aiming points probably did some damage, the target being a large one. Direct hits were made on two transshipment sheds; ten or twelve of the twenty-four tracks on the sidings were damaged, and some rolling stock was destroyed, damaged, or derailed. Without doubt the attack inconvenienced the Germans, but it was clear that to do lasting damage to such a target, a larger force of bombers would be necessary.

The 97th met with slight opposition on its first combat mission. Flak was minimal, slightly damaging two B-17s. Only a handful of German fighters—Bf 109s—showed up, three of which attacked without result. No US personnel were killed or wounded, with the exception of a navigator and bombardier lightly injured when a pigeon struck their aircraft, shattering the B-17’s plexiglass nose cone. None of the six planes of the coastal diversionary flight were lost or damaged. At precisely 1900 hours the first B-17 touched down at Grafton Underwood, followed one after another by the remaining seventeen. From Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, commanding RAF Bomber Command, came this message for General Eaker and his crews: “Congratulations from all ranks of Bomber Command on the highly successful completion of the first all American raid by the big fellows on German occupied territory in Europe. Yankee Doodle certainly went to town and can stick yet another well-deserved feather in his cap.”

It had been a successful mission, though there were lessons to be digested. General Eaker thought that formations needed to be tighter, so as to maximize the effectiveness of the B-17’s formidable defensive firepower. He also advised that navigators and bombardiers required additional training; the favorable weather conditions attending the Rouen-Sotteville attack could not always be assumed. As for the future, both Eaker and Spaatz thought that some time must elapse before the Eighth Air Force would be ready to strike at the German heartland. For the time being, short-range targets would be attacked, gradually penetrating closer and closer to Germany, the raids increasing in size as more heavy bomb groups became operational.

But a long—and unanticipated—apprenticeship lay ahead. Considerations of grand strategy—the Pacific, Atlantic, the Mediterranean—generated competing requirements for equipment and trained air and ground crews that limited the scope of Eighth Air Force’s operations. For this reason, the full-scale Combined Bomber Offensive had to be postponed to the summer of 1943. The operations conducted in the meantime were too small in scale really to test the theory of daytime precision bombing or produce decisive strategic results, though they were most useful in refining tactics and building up a cadre of experienced aircrew. Even so, the ten months following Rouen-Sotteville were frustrating ones for American airmen. Prewar planning had envisioned that a strategic air offensive would be the first heavy blow struck by the United States against Nazi Germany: the essential prelude to a cross-Channel invasion and the total defeat of the enemy. Now it was on hold.

By the autumn of 1942, the Eighth Air Force embodied VIII Bomber Command, VIII Fighter Command, VIII Composite Command (training) and VIII Service Command (logistics). VIII Bomber Command had three wings, each with two or three heavy bombardment groups. As these became operational, more missions were able to be flown — usually small in scale, invariably against targets in occupied Europe on or near the coast. RAF Fighter Command continued to provide most of the fighter escorts. German opposition from flak and fighters was generally light, but on 21 August came the first serious clash with the Luftwaffe. A B-17 formation that had become separated from its fighter escort was intercepted over Holland by some twenty-five Bf 109s and Fw 190s. In the twenty-minute battle that ensued, the pilot and co-pilot of one B-17 were wounded—the latter so seriously that he later died. B-17 gunners claimed two enemy fighters destroyed, five probably destroyed, and six damaged, claims that were almost certainly inflated. The German pilots, apparently impressed by the bombers’ defensive firepower, did not press home their attack. But 21 August was an omen. From then on the Eighth encountered persistent, increasingly heavy fighter opposition.

On 6 September, forty-one B-17s of the 97th BG and the newly operational 92nd BG attacked the Avions Potez aircraft factory at Meaulte in France. Despite a subsidiary attack on the nearby Luftwaffe base, intended to keep enemy fighters on the ground, the main mission ran into stiff resistance, mostly from Fw 190s. Several were claimed destroyed or damaged, but two B-17s were lost.

Still, the Eighth Air Force’s early missions appeared to show that the concept of daylight precision bombing was viable. Bombing accuracy had been fair to good, with significant damage to targets. The B-17E proved robust and well capable of defending itself, and losses had so far been light. The stage seemed set for further development of a European strategic air offensive.

But in late October 1942 the Eighth received a new directive from General Eisenhower. With the invasion of French North Africa (Operation TORCH) impending, great numbers of troops and huge amounts of material would be moving by sea from Britain to North Africa. It was vital to protect those convoys from both U-boat and air attack. Eisenhower therefore directed the Eighth to prioritize attacks on the German Navy’s U-boat bases on the Atlantic coast of France: Lorient, St. Nazaire, Brest, La Pallice, and Bordeaux. Shipping and docks at Le Havre, Cherbourg, and St. Malo came second, along with aircraft factories, repair facilities and airfields. Transportation and industrial targets were relegated to third place.

This directive was received by the American airmen with mixed emotions. By shifting the Eighth’s mission to the support of TORCH, it effectively put the strategic air offensive against Germany on the back burner. On the other hand, the heavy bombers were now knitted into the fabric of Allied grand strategy. The “war against the sub pens” would remain the focus of Eighth Air Force operations until the spring of 1943.