It may seem coldhearted to observe that last week’s assassination of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson was instructive in several respects, but such was the case. Most obviously, it revealed just how many people on the broad Left are okay with terrorism if it serves what they regard as the greater good. Though few of the comrades were willing to say that in so many words it was detectable in such statements as I don’t condone Brian Thompson’s murder, but… Well, sorry, but your but tells me that you do condone his murder: You think that he got what was coming because insurance companies are evil deniers of healthcare to the toiling masses. Well, progressives have become addicted to assassination porn, haven’t they?

Behind this callous attitude is the belief that healthcare is in the category of human rights. That is, somebody or other is obliged to provide it, regardless of the cost. Substack writer Barney Quick has disposed of this claim with brisk efficiency, and I encourage you to read the whole thing. But this statement sums up his argument: “A right cannot depend on the volitional activity of one’s fellow human being.”

Exactly.

A good deal of confusion exists around the concept of human rights. In the United States that concept is embodied in the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to our Constitution. The first thing to notice about the rights enumerated in those ten amendments is that they’re primarily, though not exclusively, negative rights. Famously, the First Amendment states that:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Yes, some rights established in the Constitution and the laws of the United States do compel the government to take positive action. An example is the exercise of the franchise. Every citizen has the right to participate in the political process, and this obliges government at all levels to make such participation possible by organizing elections, establishing polling places, assuring electoral integrity, and so forth. All this costs money, of course, and some portion of the taxes we pay go to finance the electoral system.

If it were true that healthcare is a human right, the same obligation to take positive action toward that end would have to be acknowledged. But on whom would that responsibility fall? The usual answer to that question is government, in the form of what is called socialized medicine. But though this sounds neat and tidy, complications soon arise. In the example given above, exercise of the franchise, the measures necessary to effectuate it are obvious, limited, and not excessively costly. The same cannot be said of healthcare.

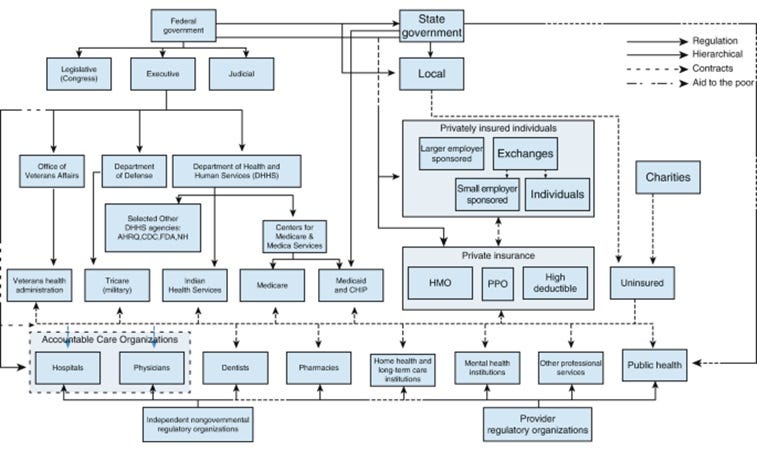

The claim that healthcare is a human right immediately summons forth the question: What, precisely, is the working definition of healthcare? In the United States and all advanced countries, the healthcare system is one of the biggest sectors of the economy, embracing a highly complex amalgam of goods and services. And contrary to what many people believe, few such systems really meet the definition of socialized medicine. In Germany, for instance, healthcare coverage is based on a government mandate requiring all citizens to have healthcare coverage, which can be provided by either government or private insurance plans. The system is primarily funded by a payroll tax, paid by both employees and employers. Britian’s National Health Service is closer to socialized medicine, but even so there are some services, such as dentistry, for which patients must pay out of pocket.

All such systems are exceedingly costly, and in recent decades demographic changes have placed an increasing financial strain on them. In practical terms, therefore, the so-called right to healthcare is really a defined benefit, dependent on available resources. If there’s a shortage of heart surgeons or hospital beds, the availability of heart surgery or hospitalization is limited by that shortage. Healthcare may be proclaimed to be a human right, but it’s the dismal science of economics that calls the tune.

In the context of healthcare, rationing is a dirty word. But since healthcare resources are finite, any healthcare system, be it based on private insurance, government coverage, or a combination of the two, must engage in rationing. This takes various forms. Because demand exceeds supply, organ transplants are rationed, usually by directing available organs to those most likely to benefit from them. If, for example, the choice lies between an otherwise healthy man of forty-two and a man of seventy-five with COPD and diabetes, the heart will go to the former. Or since hospital beds are a finite resource, various measures, such as shortening hospital stays, are used to align supply with demand. This is unpopular; people complain. But what’s a hospital administrator to do?

Nor can the profit motive be wrung out of the healthcare system. Medical professionals cannot be expected to work for free. New treatments, drugs and medical technologies do not appear of themselves. The shareholders of the Acme Bedpan Company would still expect a return on their investments. If the United States were to go to a single-payer system, among the biggest winners would be medical services companies to whom much of the new system’s administrative workload would be contracted out.

At various times in various places, food, clothing, shelter, education, and gainful employment have been similarly designated as fundamental human rights. How well that designation is honored in practice may be gauged by the sorry state of public education in America, where the very people who call it so are actively engaged in transforming schools into progressive propaganda mills. Or it may be gauged by the problem of homelessness in America, where attempts to get homeless people off the streets are opposed by self-appointed advocates for the homeless. The late Jordan Neely was but one of those people’s sad victims.

Probably there are various ways in which the US healthcare system could be improved—but enacting a law or a constitutional amendment designating healthcare as a fundamental human right would do nothing to further that objective. Probably it would make the current unsatisfactory state of affairs measurably worse. I shudder to think what the results would be if our none-too-competent federal bureaucracy had to assume the responsibility for running a single-payer healthcare system covering 330 million Americans.

Oh, and assassinating the CEOs of private health insurance companies wouldn’t improve things, either. Sorry, comrades.

There's a good post over at Noahpinion by liberal economist Noah Smith about the economics of health care. Insurance companies are secondary middlemen. The providers, especially hospitals, are the biggest cost center by far, much bigger than insurers or drugs/technology. Hospitals are a particular culprit because they, like US universities, have very bloated and costly administrations.

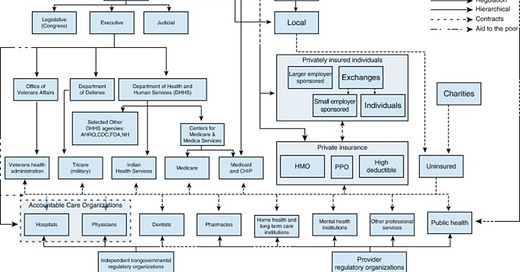

Good article! Double those bubbles in the diagram and you’ll have the picture. There are so many sections of each company, it’s astonishing. The original Obamacare diagram was a nightmarish maze of bureaucracy. Have worked in health insurance x 30 years—it’s not us! It’s the hospitals. The minute the insurance caps were removed, costs for bone marrow transplants were doubled. I wish I could say the organs go to the right people, but as a transplant case manager I can tell you they don’t. Centers will transplant anyone if there’s insurance to pay for it. 😕