During World War Two, the air defense of the Reich was a primary responsibility of the Luftwaffe (German Air Force). This article describes the organization and equipment of the Luftwaffe fighter units that fought that air battle by day and night. The organization and equipment of the Flak (antiaircraft gun) units of the Luftwaffe that were committed to the air defense of the Reich will be described in a subsequent article.

Luftwaffe Fighter Units

The Luftwaffe’s basic flying unit was the Geschwader, roughly equivalent to though smaller than a US Army Air Forces wing and operating one aircraft type. Those equipped with single-engine fighters were titled Jagdgeschwader (hunting wing), and those equipped with twin-engine fighters were titled Zerstörergeschwader (destroyer wing). During the war a third type was added: the Nachtjagdgeschwader (night hunter wing), mostly flying twin-engine, radar-equipped fighters.

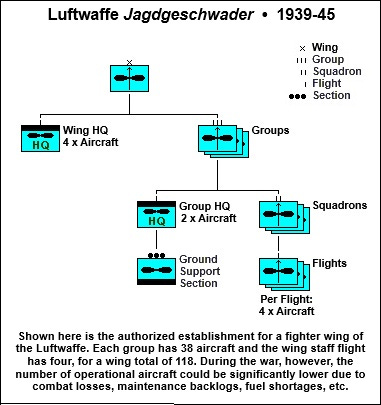

All three wing types were formed with three or four Gruppen (groups), each with three or four Stafflen (squadrons), each squadron with twelve to sixteen aircraft divided into three or four Schwärme, (flights) each with four aircraft. The wing headquarters had a Stabsschwarm (headquarters flight) with four aircraft for the wing commander and his staff officers. The groups also had a headquarters flight with two or three aircraft. The strength of a group could range from thirty-five to forty-five aircraft; the strength of a wing with three groups could therefore range from 105 to 135 aircraft—the lower number being more typical.

The ground echelon of a group consisted of an air signal platoon, an aircraft maintenance detachment, and a firefighting platoon whose personnel doubled as military police. This dual-purpose platoon was attached from the SS. Both the wing and group HQs included various Wehrmacht-Beamte (military administrative officials). These officials were members of the armed forces, their positions corresponded to officer or senior noncommissioned officer (NCO) ranks, but they had no combat role and their authority was limited to their specialty, such as personnel matters or logistics.

It should be noted that during the war, the combat strength of a Luftwaffe fighter wing could deviate significantly from the above standard due to combat losses, maintenance backlogs, fuel shortages and the like. A squadron, for example, might have only eight or even six operational aircraft.

The wings were numbered and were usually referred to by their abbreviated title, e.g. JG 54, ZG 1, NJG 3. The subordinate groups were identified by Roman numerals, e.g. I/ZG 76, and the squadrons were identified by Arabic numerals that ran consecutively through the groups. Thus if a wing had three groups, each with three squadrons, the latter would be numbered 1 through 9, e.g. 4/JG 2. Some wings had honorary titles, e.g. ZG 26 “Horst Wessel.”

A wing was usually commanded by a colonel or lieutenant-colonel, a group by a major or senior captain, a squadron by a captain or first lieutenant, and a flight by a first or second lieutenant. As in the Royal Air Force, some pilots were NCOs rather than commissioned officers.

The group was an autonomous organization that could be and often was detached from its parent wing. In June 1944, for instance, HQ JG 2 with I/JG 26 and III/JG 26 were stationed in France at Lille-Nord, while II/JG 2 was stationed at Mont-de-Marsan.

The Luftwaffe also included separate groups and squadrons, usually formed for special missions or purposes. A few of these were fighter units and an example is Jagdverband 44 (Fighter Detachment 44) which was formed in March 1945 with a cadre of experienced pilots to operate the Me 262 jet fighter. It had between twenty and twenty-five aircraft.

Operational Command and Administrative Support

Higher headquarters for fighter units were the Jagd-Division and the Jagdkorps (fighter division and fighter corps) These were specialized versions of the Fliegerdivision and Fliegerkorps (air division and air corps) and were roughly equivalent to USAAF air divisions or commands. Fighter divisions were normally commanded by a major-general, fighter corps by a lieutenant-general or a full general.

The highest echelon of command in the field was the Luftflotte (air fleet), equivalent to a USAAF numbered air force. Luftwaffen-Befehlshaber Mitte (Air Force Commander Central Sector), renamed Luftflotte Reich early in 1944, was the higher headquarters charged with the air defense of Germany. An air fleet was responsible for all operational functions of the Luftwaffe in its allotted geographical area. Air fleets were commanded by colonel-generals or field marshals.

These operational units of the Luftwaffe were supported by the Luftgaue (territorial air districts), responsible for training, administration, maintenance, signals, recruitment and reserve personnel. The air defense of the Reich involved almost all of the air districts located in Germany proper. A Luftgau was normally commanded by a major-general.

The Oberbefelshaber (commander-in-chief) of the Luftwaffe was Hermann Goering, who held the unique rank of Reichsmarschall. His command was exercised through the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL): the Luftwaffe High Command.

Fighter Aircraft

At the beginning of the war, the Luftwaffe possessed two front-line fighters: the single-engine Bf 109 and the twin-engine Bf 110. Both were often called Messerschmitt after their designer, Willi Messerschmitt of Bayerische Flugzeugwerke AG, renamed Messerschmitt AG in 1938 when he took over as board chairman and managing director of the company. The two-letter prefix to the model number identified the manufacturer, and though later aircraft produced by the company bore the prefix Me, it was not applied retroactively to the 109 and the 110.

The Bf 109 entered production in 1936 and by 1939 almost all of the Luftwaffe’s fighter wings were equipped with the type. The latest version in service at that time, the Bf 109E-1, was armed with a pair of 7.92mm machine guns over the engine and firing through the propeller, and two 20mm cannons in the wings, firing outside the propeller arc. The Bf 110 entered production in 1937 and by 1939 it equipped four destroyer wings. It was armed with four 7.92mm MG and two 20mm cannons in the nose, and one rear-firing 7.92mm MG on a flexible mount. These two aircraft were continually updated and remained in service up to the end of the war, and they played a major role in the air defense of the Reich.

In 1941 a new fighter, the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, entered service. The first production model, the Fw 190A-1, was armed with four 7.92mm MG, two over the engine and one in each wing root, all firing through the propeller, and two 20mm cannons in the wings, firing outside the propeller arc. The Fw 190 was continually updated and served throughout the war.

These three aircraft constituted the backbone of Luftflotte Reich and for the air defense mission they were specially modified. For example, the Fw 190A-8/R2 was armed with two 13mm MG (replacing the 7.92mm MG), two 20mm cannons, and two 30mm cannons. It could also carry a pair of 210mm unguided rockets in underwing launch tubes. The cockpit and windscreen were armored to protect the pilot. In this form the Fw 190 was a potent bomber destroyer.

The Bf 109 was also modified to increase its firepower, but when the American bomber formations acquired fighter escorts, it was used mostly to protect the bomber destroyers. Early in the war, the Bf 110 had proved a failure as a long-range escort fighter, but it was more successful as a bomber destroyer and as a radar-equipped night fighter.

Other night fighters were bomber conversions, for example the Ju 88C-6. In 1943, the He 219 entered service. This was a purpose-designed and very effective night fighter, but it was complicated and expensive to manufacture and only three hundred or so were built. Late in the war, the Me 262 jet fighter and the Me 163 rocket fighter joined the battle. The former was a formidable bomber destroyer and the latter was a truly futuristic design, but they arrived too late to turn the tide of battle.