"Democratically Elected Leaders"

On the Left's historically illiterate indictments of the United States

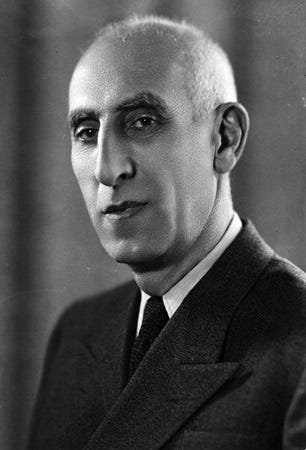

You know how the narrative goes. It’s right there in the first paragraph of Wikipedia’s article on the 1953 Iranian coup d'état. The progressive, democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammad Mosaddegh, was chased out of office by a cabal of military officers, egged on by Britain and the United States, after Mosaddegh had nationalized the assets of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC). And this, supposedly, was a blatant act of imperialist aggression that set in motion a train of events culminating in the overthrow of the autocratic Shah, the establishment of the Islamic Republic, and the 1980 hostage crisis. Here, for instance, is NPR explaining “How the CIA Overthrew Iran's Democracy in 4 Days.”

But there are problems with this narrative, beginning with the awkward facts that Mosaddegh was not “democratically elected,” nor was there any such thing as “Iran’s democracy.”

In the early 1950s, though Iran was not a democratic state neither was it an autocracy. There was an elected parliament, but it and the governments of the day were dominated by the country’s elites: primarily landed aristocrats, businessmen, clerics, and senior military officers. In theory, the Shah wielded considerable power, but in fact his freedom of action was circumscribed by the need to maneuver among and placate the aforementioned elites. It was a political system not unlike that of Great Britain in the reign of King George III.

The nationalization of the AIOC was the outcome of a dispute between Britian and Iran over the division of the company’s revenues. Under the existing agreement, this division heavily favored Britain. But Iranian demands for a more equitable arrangement met resistance in London—which served only to popularize the cause of oil nationalization.

When the nationalization bill passed, Britain’s Labour government retaliated by organizing a global boycott of Iranian oil. It also ordered the withdrawal from Iran of the British technicians who ran the AIOC’s facilities. This ensured that output would collapse, and that the small amount of crude oil that could be extracted would be unsalable on world markets. The Iranian government thus lost a major source of revenue, and the country’s economy went into a tailspin.

As a prominent member of the Iranian parliament who had served in several past governments, Mosaddegh and his National Party had led the effort to get an oil nationalization bill enacted. Its passage was a political triumph for Mosaddegh and the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, then a young man in his thirties, felt compelled to appoint him prime minister. This was in accordance with the Iranian constitution then in force, by which the monarch was empowered to appoint the prime minister and the minister of war. Mosaddegh was, alas, the wrong man for the job at such a critical time. Temperamentally, he was a stubborn old autocrat who tolerated no dissent, and his conduct was colored by a deep hatred of Britain.

After becoming prime minister, Mosaddegh asked President Harry Truman to mediate the AIOC dispute. Thus began America’s involvement in the crisis, and from the start, the US government—first the Truman Administration and later the Eisenhower Administration—took a sympathetic view of the Iranian position. In 1950, faced with similar demands from the government of Saudi Arabia, the United States had agreed to split the revenues of the Arabian American Oil Company (ARAMCO) with the Saudis on a 50/50 basis. This was much more generous than anything that the British were prepared to concede to Iran.

Mosaddegh was therefore in a strong negotiating position, given the passage of the nationalization bill and the US government’s favorable attitude. But once the discussions got down to specifics and proposals were offered, the prime minister balked. When passed the nationalization bill had been broadly popular, and probably Mosaddegh was loathe to compromise it out of existence. His attitude seemed to be that the purpose of American mediation was to champion Iran’s maximum demands rather than to facilitate a compromise. After giving the impression in private that he accepted them, he publicly rejected two American compromise proposals, one crafted by the Truman Administration and one by the Eisenhower Administration, both very favorable to Iran—much to the exasperation of the US government.

While these futile negotiations stumbled along, the situation in Iran went from bad to worse. The government was bankrupt; the economy was moribund. It was clear that nationalization of AIOC had been disastrous for Iran, and popular discontent was rising. Among the Iranian elites there was muttering against the prime minister. And as the situation deteriorated, the leaders of the Iranian armed forces looked on with indignation and dismay. Rumors that a coup was in the works circulated in the capital.

Mosaddegh‘s reaction to all this was true to form: a purge of his critics in parliament and the military. Also, the Shah, who was known to fear and despise his prime minister, was stripped of most of his political prerogatives, for instance being specifically barred from meeting or communicating with military officers. The autocratic prime minister now seemed intent on the creation of a left-wing authoritarian state.

Many leading Iranian politicians implored the US ambassador in Tehran for American assistance in the ouster of Mosaddegh. They were politely rebuffed, but in Washington fear was growing that the crisis would bring a communist government to power. The prime minister himself stoked those fears in an attempt to extort financial assistance from the Americans. If such assistance was not forthcoming, he declared, a communist takeover of Iran was likely.

This blackmail attempt apparently convinced the Eisenhower Administration that Mosaddegh had to be given the push. The obvious solution was for the Shah to dismiss the prime minister, as he was constitutionally empowered to do. But the monarch was hesitant to take such a risky step and agreed to it only after receiving assurances of American support. At first this ploy appeared to backfire, and the Shah fled the country. But when word got around that the monarch had dismissed Mosaddegh, the military group that had been plotting a coup all along swung into action. To the accompaniment of raucous street demonstrations, troops moved in, occupying key points in the capital. Mosaddegh was taken into custody, the Shah returned, and the leader of the coup, Lieutenant-General Fazlollah Zahedi, replaced Mosaddegh as prime minister.

There can be no doubt that the CIA and British intelligence played a role in the coup. They certainly encouraged it and gave it some support. But by the time the coup took place, Mosaddegh’s popularity had evaporated. The economic calamity that he’d brought down on Iran was the major factor in this, but in addition many people were angered by his contemptuous treatment of the Shah, who at that time was a respected, even a popular, figure. The prime minister had also lost the support of the clerical class, who distrusted his secularism and left-wing political stance. The coup was primary an Iranian affair, and few tears were shed at Mosaddegh’s overthrow.

Subsequently, Mosaddegh was tried for treason and sentenced to death, but the Shah intervened to get his sentence reduced to life imprisonment. The deposed prime minister served three years in a military prison and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. He died in 1967 at the age of eighty-four.

It’s reasonable enough to question whether the United States was right to play a role in the 1953 Iranian coup—but that’s not the Left’s intention. In their long-running campaign to demonize America and the West, they’ve created an alt-history version of events that excludes or distorts many of the facts of the case. Mohammad Mosaddegh was not a “democratically elected leader” and had he remained in power, Iran would most probably have evolved into an authoritarian state similar to the one that evolved under the Shah. Indeed, Mosaddegh‘s character—arrogant, autocratic, disdainful of criticism and opposition, infused with hubris—was curiously similar to the Shah’s in his later years.

One final point bears mention: Since the 1980 revolution that brought the ayatollahs to power in Iran, the Islamic Republic has repeatedly cited the 1953 coup as a crime against the Iranian nation, perpetrated by the Great Satan—America. This is a prize specimen of hypocrisy, given that in 1953 the Iranian clerics heartily approved of the coup that removed from power a man they reviled as a secularist and an apostate.

That’s how ideologues, be they of the Right or of the Left, treat—or rather abuse— history. If the facts don’t fit the narrative, then the facts must be distorted or suppressed. Remember that the next time the comrades start singing the praises of some “democratically elected leader.”

Read Abbas Milani's biography of the last Shah. It's all there. Milani was an Iranian student dissident in the US in the late 1970s and believed the nonsense about Iran served up by the New Left (and recycled by the mullahs). Later, he uncovered the truth as he worked his way toward becoming a professional historian at Stanford. (A career like his would be impossible today.) The funny thing is that the facts were always available. It's just that many chose to ignore them in favor of an ideological concoction.

Iran in 1953 was a constitutional monarchy, and what happened was simply the machinations of parliament, king, and prime minister. There was no coup, American-engineered or otherwise. The two outsiders traditionally interfering in Iranian politics were Britain and Russia, which was still true then. The Shah was far from an American puppet, as his later career demonstrated. The phony "narrative" was always a hoax.

P.S. A very important related book is Michael Doran's Ike's Gamble, about the 1956 Suez Crisis, a terrible mistake by Eisenhower, under the sway of bad ideas and John Foster Dulles. They forgot (but belatedly remembered) the first rule of foreign policy: reward your friends and punish your enemies.

Recent (fairly recent) history will remind us that Iran typically gets poor leaders.

And the Iranian people are often complicit in these bad choices.

Britain and Russia felt compelled to occupy Iran during WW2. A smarter leader might have steered his country away from this fate (see Turkey in the same period).

The Ayatollahs that followed the Shah are determined to push the country back 500 years (socially and in standard of living).

The ayatollahs came in with the enthusiastic support of many Iranians and the acquiescence of the Carter administration.