Democrats and progressives—you should pardon the redundancy—are fond of citing the fall of Germany’s Weimar Republic in support of their democracy-in-danger narrative. Trump = Hitler, MAGA = the Nazi Party, Biden = the elderly, failing president, etc. No, wait, Biden’s no Hindenburg. Why, Karine Jean-Pierre can hardly keep up with the guy! But you get the idea, and it’s an idea that flatters those who style themselves dauntless defenders of “our democracy.” They get to pose as fighters against fascism without breaking a nail on a bombing raid over Germany or becoming nauseous during a trip by landing craft to Omaha Beach.

But when I survey the current, debased state of American politics, another historical precedent comes to mind: the Republic of Pals, as the French Third Republic was derisively nicknamed.

The story of the Third Republic has a little something for every type of pessimist. It was during the Republic’s early years that the seeds of European fascism were sown. Long before Dr. Goebbels cooked up the Night of Broken Glass, the Dreyfus Affair (1894-1906) touched off a horrific outburst of antisemitism in what was supposedly the world’s most liberal, civilized nation. Indeed, what’s happening right now in the Middle East may be traced back to the Dreyfus Affair, for the founding father of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, personally witnessed the military degradation of Commandant Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer of the French Army, after the latter’s conviction on trumped-up charges of espionage and treason.

It was a barbaric spectacle. On the morning of January 5, 1895, five thousand troops paraded at the École Militaire in Paris to witness the ceremony. As the drums rolled and a crowd of 20,000 looked on, the buttons were plucked from Dreyfus’s tunic, the red stripes were torn from his trousers, the epaulets were ripped from his shoulders, and his officer’s sword was broken in two. He was then paraded around the barracks square while the crowd howled for his death and the extirpation of the Jews. But since the death penalty had been abolished some time before, Dreyfus’s sentence was life imprisonment on Devil’s Island, a penal colony off the coast of French Guiana in South America. Herzl later remarked that what he’d seen that day was the thing that convinced him of the need for a Jewish state, and though he need not be taken literally—much else influenced him—the Dreyfus Affair certainly played a role in his thinking.

Aside from manifesting a virulent strain of antisemitism in French society, the Dreyfus Affair deepened the nation’s political divisions. In general, the broad Right—monarchists, Bonapartists, aristocrats, the officer corps of the Army, the Catholic Church—stood against Dreyfus and reviled the Jews as alien interlopers, actual or potential traitors, spreaders of corruption. These groups, which overlapped at many points, also hated and reviled the Republic itself. The broad Left—supporters of republicanism, socialists, bourgeois intellectuals like Émile Zola and Anatole France—stood for the innocence of Dreyfus, believing him to be the victim of a gross miscarriage of justice. In the end they prevailed, but the wounds opened in the body politic by the Dreyfus Affair never closed.

That the Third Republic was a bourgeois regime was another fatal flaw. First and foremost, the government represented the wealthy and well-to-do middle class. Effectively, it excluded the working class from participation in politics, while doing nothing to advance its economic interests. In every labor dispute, the government sided with the business owner against the workers—sometimes to the point of calling out troops to break up strikes. Taxation fell disproportionately on the working class and for decades the government refused to set up a system of social security like the one next door in Germany that Bismarck had instituted.

Over time, the working class’s situation improved somewhat, but by then its estrangement from the Republic was profound. It’s true that during the Great War, a national truce of sorts prevailed, with all classes and factions united in the defense of the national soil. But this Union Sacrée disappeared once the guns ceased fire, nor did it reappear 1939-40, when it was so badly needed.

The constitution of the Third Republic and its political culture only exacerbated the divisions, hatreds, and resentments that crisscrossed French society. As originally promulgated in 1875, it provided for a two-house legislature (Senate and Chamber of Deputies), and a President of the Republic chosen by both houses of the legislature and serving a seven-year term. A governing Council of Ministers, responsible to the Chamber, was to be appointed by the President. The monarchist faction thought that such a constitution could easily be adapted for a constitutional monarchy, but all it produced was deadlock, with republicans controlling the Chamber and monarchists controlling the Senate. Only in 1880 was the crisis resolved, with the President reduced to a figurehead and all real power concentrated in the legislature.

Governments were thus at the mercy of the Chamber and the Senate, which could overthrow them on a whim. The resulting instability was somewhat ameliorated by the fact that though governments came and went, much the same people served as government ministers in successive cabinets. But the legislature’s backroom dealmaking, logrolling, financial shenanigans and periodic scandals did nothing to help its image or to raise the prestige of the political class.

The France that emerged from the inferno of the Grear War was a much-diminished nation. Proportionately, France suffered higher casualties—killed, wounded, missing in action—than any other belligerent. A total of 1,315,000 Frenchmen died or went missing on the battlefield, representing twenty-seven percent of all men aged between eighteen and twenty-seven. Of the 4,200,000 war wounded, nearly a million and a half were permanently maimed. Thanks to the war, from 1915 to 1919 there were 1,400,000 fewer births than would otherwise have taken place—this in a country whose birthrate was already in decline before 1914. And of course, much of the fighting had taken place on French soil, inflicting terrible damage on the nation’s physical fabric. Though on the face of things France was now Europe’s predominant power, the country’s long-term prospects were bleak.

As with the Weimar Republic in Germany, there was for France an interval in the Twenties of prosperity and hopefulness. An economic recovery was complemented by the Pact of Locarno (1925), a broad-based diplomatic settlement that was widely seen as a guarantee of lasting peace. But the horizon was already clotted with storm clouds. In Italy, Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime was well established. And in 1929 came the Wall Street stock market crash, herald of the Great Depression.

The Depression was a catastrophe for Germany, whose economy went into a tailspin that destroyed what faith remained in the Weimar Republic and facilitated Hitler’s rise to power. His appointment as German chancellor on January 30, 1933, spelled the end of liberal democracy in Germany and may also be taken as the death knell of the Third Republic.

Though the economic downturn inflicted less damage on France than it did on the United States, Britain and Germany, the situation was bad enough. Prosperity evaporated, unemployment soared, the government proved unable to cope with the crisis, totalitarian ideas gained ground on both the Left and the Right. An apotheosis of sorts was reached on the night of February 6, 1934, when the broad Right, by then deeply infected with fascism, massed on the streets of Paris, determined to sweep away the government and bring down the Republic. There followed the worst political violence seen in the capital since the Commune (1871), and though the Right’s attempt to seize power failed, the radical polarization of French politics was out in the open.

The foregoing account is of course a sketch, touching on the high points of a complex, fascinating, and depressing story. But the themes of class division, political instability and polarization, loss of faith in government and other institutions, collapse of national morale and national resolve are there—and to a greater or lesser extent they’re applicable to present-day America.

Analogies are suspect because they can so easily be pushed too far, as when progressives denounce Trump as the American Hitler and MAGA as a reincarnation of the Nazi Party. It seems right, however, to characterize them as the bearers of populist authoritarianism, inimical to liberal principles. Similarly, though postmodern progressivism is not Bolshevism, it seems right to characterize it as a form of illiberal elitism, opposed at many points to the norms of the American constitutional order, including its conception of civil rights and liberties. Nor are America’s class divisions as deep as those that plagued the Third Republic: Primarily they represent the obsession of small but vocal minorities with concepts of class, race, ethnicity and gender. Still, the ideas embodied in their chatter are troubling—as the current upsurge of antisemitism in America attests.

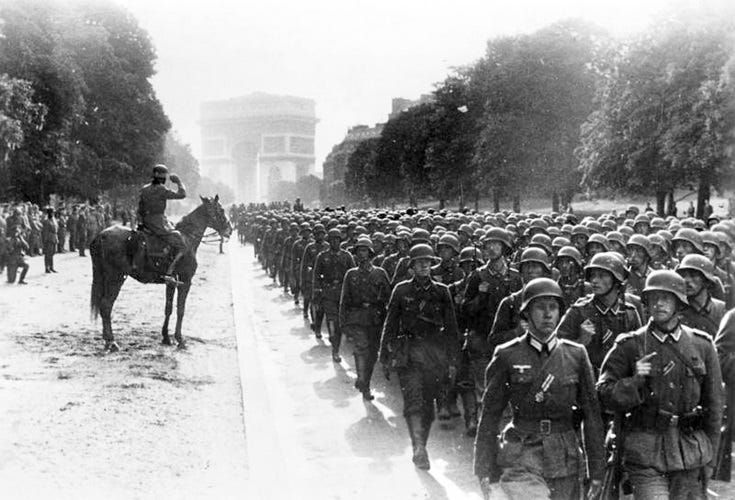

The collapse of national morale and will, on the other hand, is a problem just as urgent and dangerous for America as it was for the Third Republic. In May 1940, France was decisively defeated by Nazi Germany in just ten days, and though purely military factors played a role in the catastrophe, its fundamental causes were paralysis of will, the virus of defeatism, and simple despair. From the cowardly and disgraceful abandonment of Afghanistan by the Biden Administration to the vile rants of the national conservatives against Ukraine, America exhibits the same symptoms today.

This is not to say that the Land of E Pluribus Unum is likely to meet an end like that of the French Third Republic. But an America diminished, isolationist, unwilling to lead or deter, would be a less secure nation, a poorer nation—economically, psychologically, morally—a shell of its former self. There are, alas, people in America who are working hard to make that dismal vision a reality. They think that by sweeping away all ideas of American exceptionalism, American self-confidence, American patriotism, they can clear the ground for their own illiberal projects.

That can’t be allowed to happen.

I think a key point missing in analyses of this genre is a country’s history of democracy, and the value the culture places on democratic rule. Germany had basically zero historical or cultural appreciation for democracy. France was not a longstanding democracy either, though not as distant from democracy as Germany was.

The United States is probably second to England globally in historical and cultural resistance to the idea of autocracy.

I don’t think democracy will be defeated easily in America. I think it would be more likely overrun by a foreign army than an insurrection to institute a dictatorship.

Weimar Germany was a country that had been recently run under Kaiser Wilhelm, a true autocrat. In contrast, Queen Victoria, his grandmother in England, had a far more narrow role as the monarch in England.

German culture valued blind obedience and the collective over the individual.

The cultural framework necessary for democracy to thrive was absent.

Germany had a longstanding militarism as a prominent part of its culture. Its role as a belligerent in WWI illustrates the extent of that.

American individualism preceded the Revolutionary War. It is a key component of American culture.

Perhaps the only valid comparison between the United States in the 21st century and Germany in the 1930’s is the true and inarguable existence of evil, and the fact that G-d has been removed from public discourse, in Germany from the church itself, in both places.

Could Americans become evil like the Nazis? Yes. Because evil exists.

Would it take the shape or trajectory of a culture like Germany of the 1930’s? No. It would go a different way but be just as evil.

Are the takers down of hostage pictures likely to mount an armed rebellion against the US government? I think it more likely that they weaken the US from the inside and render America completely unable psychologically and militarily to defend itself.

I think the left’s victim culture is a powerfully corrosive force that has infiltrated the right also. It’s hard to reverse and it undoes a civilization.

Army recruitment rates are down. Birth rates are down. Neither required an insurrection. Just a corrosive and pervasive sense of helplessness and a blind tendency to blame America.

"...much the same people served as government ministers in successive cabinets."

I can argue that the mandarins in the State Department and and other agencies frustrate effective leadership.

But our leadership (Executive, Legislative and to some extent Judiciary) are also failing us.

The military had been the one branch of the government that stood for something and united Americans in respect.

But our generals no longer speak of victory. Their objectives are now "nation building" or "administration" or "peace keeping".

Our generals are careerists whose focus is getting that lucrative retirement position with defense contractors.

Our military no longer produces a Billy Mitchell or a Smedley Butler - gadflies who challenge the status quo and force public discussion.

Reform will come from the bottom - Americans in sufficient numbers and with loud enough voices that Washington will have to listen.

People like you and Claire Berlinski (and many others) are the voices that will educate Americans about the path that we are on.