Note: I wrote this article a couple of years ago; rereading it now I thought it worthwhile to share “Show Me a Radical” with the subscribers I’ve acquired since then.

The life and death of Fay Abrahams Stender recalls F. Scott Fitzgerald’s lapidary quip: “Show me a hero and I’ll write you a tragedy.” For she was indeed a hero of sorts and her life ended on a note of tragedy: Stender died by her own hand in a lonely Hong Kong apartment on March 19, 1980. But really her death should be classed as a homicide, for it was the cause to which Fay Stender dedicated her life that really killed her.

The dead woman had been a radical lawyer, famed for her defense of the Black Panthers, the Soledad Brothers and the Black Guerrilla Family, the latter a San Quentin prison gang founded by her client, political comrade and lover, George Jackson. On May 28, 1979 she was shot five times in her Berkeley home by Edward Glenn Brooks, a recently paroled convict. Though Stender survived, the shooting left her paralyzed from the waist down.

Police theorized — but could not prove — that the hit had been ordered by a convict named Hugo “Yogi” Pinell, who’d succeeded to the leadership of the BGF after George Jackson’s 1971 death in a bloody attempted prison break. It was said that Stender had been marked down by the group as a traitor after she and Jackson fell out over her refusal to help him break out of San Quentin and her abandonment of the revolutionary cause. Though Brooks’ connection to the BGF was never established, many of Fay’s friends and former comrades assumed that he was acting on the orders of the group.

The attempted murder of Fay Stender rocked the Bay Area’s radical legal community, of which she had been so prominent a member. Brooks was eventually tracked down, arrested and charged with attempted murder, his trial taking place in January 1980. Several of the radical lawyers who usually took such cases declined this one. Some found themselves hoping that the police and prosecutors they’d so often denounced as racists hadn’t made some mistake that would enable the shooter to squirm off the hook. Stender herself testified as a witness for the prosecution. It was the last of her many courtroom appearances, and there were those among her former comrades who bitterly denounced her for it. Ultimately Brooks was convicted and sentenced to seventeen years in prison.

But her assailant’s conviction brought Stender no peace. Depressed, tormented by chronic pain, wracked with fear, she abandoned her home in Berkeley, renting an apartment in San Francisco whose location she disclosed to none but a few close friends. There she languished as a virtual prisoner, confined to a wheelchair, terrified by the prospect of another attempt on her life. In March 1980 she fled to Hong Kong. Two months later, Fay Stender was dead of a drug overdose at the age of forty-eight.

In some ways she seemed an implausible candidate for such a life, and such a death. Many Sixties radicals — David Horowitz for instance — were red-diaper babies, born into East Coast families with traditions of left-wing political activism. Not Fay Abrahams. Her parents were conservative, observant, middle-class Jews with deep roots in California. The family moved from San Francisco to Berkeley in 1942 and it was there that she encountered the intellectual and political milieu that was to produce the New Left and determine the course of her own life.

Early on, Fay displayed considerable musical talent and her mother attempted to steer her into a career as a concern pianist. But the daughter rebelled, choosing instead to attend Reed College in Oregon in pursuit of a degree in literature. She was a restless, dissatisfied young woman— searching, as a friend later put it, for something that would give her life greater meaning. Ultimately she chose to attend law school at the University of Chicago, another milestone on her road to radicalism. There, one of Stender’s law professors asked her to help him prepare an appeal on behalf of Morton Sobol, the “third man” in the notorious Rosenberg case, at that time the Left’s most cherished cause célèbre.

In Chicago she also met a lawyer named Marvin Stender, the head of the local chapter of the left-wing, officially proscribed National Lawyers Guild. After a brief courtship they married, and by 1960 they were living back in Berkeley. The Stenders regarded their marriage as a partnership on behalf of the oppressed; nowadays they’d be called social justice warriors. Perhaps surprisingly in view of the turbulent personal and political events already on the horizon, the marriage proved durable and they had two children together, a son and a daughter. Only at the end of the Seventies, after Fay came out as a lesbian, did they separate.

Inevitably, Fay and Martin Stender became involved in the civil rights movement. For her, it was a classic case of the personal embracing the political. In the struggle against segregation, racism, injustice, poverty, all the evils that held black Americans down, she discovered that sense of meaning and purpose whose absence from her life had always troubled her. Stender became the force behind the Bay Area Friends of SNCC: the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a radical civil rights group founded by Stokely Carmichael. In 1964–65, she and her husband went south to work on SNCC’s behalf for civil rights in Mississippi. In 1967, when Carmichael's burgeoning radicalism led him to eject all white members from SNCC, Stender accepted and even defended his action — this despite the fact that many of the purged whites were Jews like herself. The simmering antisemitism behind Carmichael’s move was a blemish that she refused to acknowledge.

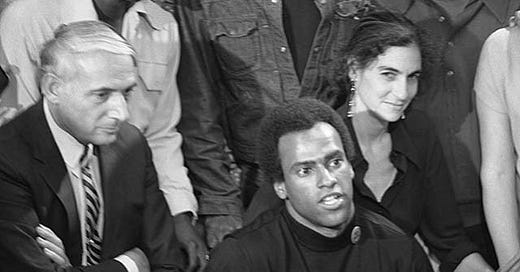

Moving on from SNCC, Stender became associated with another radical group, the Oakland-based Black Panther Party, which still welcomed white support. The party, which had evolved from an Oakland street gang, retailed a Marxist analysis of racism. Its program called for the creation of a revolutionary coalition of oppressed blacks and radical whites to oppose and ultimately replace the existing system. The Panthers’ co-founder and leader, Huey Newton, was vividly charismatic, with a veneer of intellectual sophistication masking a deep-rooted nihilism.

On the night of October 27, 1967, occurred the incident that was to determine the course of Fay Stender’s life — and lead to her ultimate death in Hong Kong. After leaving a party celebrating the end of his probation for a knife assault three years earlier, Huey Newton was stopped by an Oakland police officer. In a hail of gunfire, the officer was killed; Newton and another officer, who’d been called to the scene as backup, were both wounded. Thus was the stage set for the decade’s highest-profile political trial.

Newton, charged with murder, was defended by a prominent left-wing attorney, Charles Garry, with Stender in the second chair. Formally their defense was that in the chaos of the moment, both the dead officer and Newton had been shot by the responding second officer. But Garry and Stender really sought to place the system itself on trial, citing the Oakland Police Department’s indisputable record of brutality toward blacks — and implying that even if Newton had killed the cop, his action was justified. This defense seemed to influence the jury, which temporized by convicting Newton of manslaughter. (Damming testimony from a black bus driver who’d witnessed the shooting probably deterred the jury from acquitting Newton.) Off he went to prison: San Luis Obispo Men’s Facility. But the story didn’t end there.

Huey Newton’s trial had taken place against the backdrop of America’s annus horribilis: 1968, the year of the Tet Offensive, of unrest on college campuses, of urban race riots, of chaos on the streets of Chicago during the Democratic National Convention, of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy. It was the year that confirmed the radicalization of the New Left — and of Fay Stender. With the energy and fanaticism of the true believer, she embarked on a campaign to overturn Newton’s conviction. She worked on his appeal for two years — in the end successfully. A technical flaw in the trial judge’s charge to the jury was the key that unlocked the door to Newton’s jail cell. This success made Stender one of the most celebrated radical lawyers in the country. It also introduced her to a new issue, prison reform.

But in the storm and stress of the trial and the appeals process, with revolution in the streets and the system seemingly close to collapse, Stender began to lose perspective. Visiting Newton in the San Luis Obispo Men’s Facility, she developed a close personal relationship with him—as an intimate friend, ultimately as a lover. And worse was to follow, for Newton told her about another black prisoner, who was at that time being held in Soledad Prison.

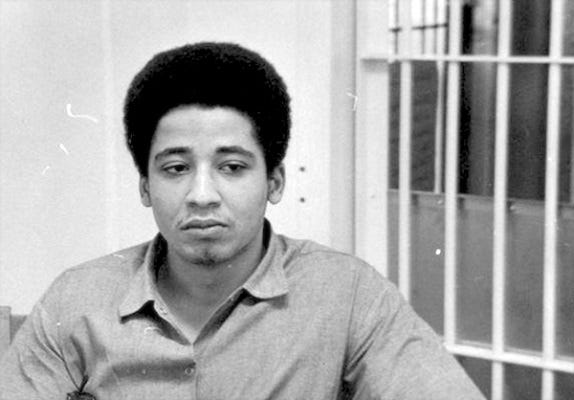

When Fay Stender first met George Jackson, she was thirty-eight years old and he was twenty-eight. Convicted of a 1961 armed robbery, he’d been in prison ever since. Over the years he’d become radicalized, cultivating the persona of a revolutionary martyr. Jackson was highly intelligent, self-educated, of striking appearance, with expressive eyes, eloquence, magnetic charm. He was also a career criminal, comfortable with violence, a man both respected and feared by fellow inmates. “He was the meanest mother I ever saw, inside or out,” one said.

The thought naturally occurs that George Jackson was a con artist, deploying a suave line of revolutionary patter to becloud his true nature and beguile white radicals like Stender. Perhaps so, but on the other hand there’s no reason why performance art and violent criminality should be incompatible with genuine revolutionary zeal. It seems plausible to think that Jackson believed every word he wrote in Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson, the best-selling book that made him a hero of the New Left.

The background to the book was a bloody one. On January 13, 1970 at Soledad Prison, three black inmates were shot and killed by a white guard during an interracial yard riot. By way of retaliation, three days later another white guard was beaten to death. Three black inmates were charged with his murder; one of them was George Jackson. The three became the Soledad Brothers, and Fay Stender became their lawyer.

Her defense strategy was the same one that she and Charles Garry had deployed on Huey Newton’s behalf: The Soledad Brothers were revolutionary martyrs. They’d been singled out for persecution because of their political activism and because they were black. Not the Soledad Brothers but the corrupt, racist system that oppressed them would be put on trial.

Once again with the energy of the true believer, Stender mobilized a cohort of Bay Area activists into a defense committee that raised hundreds of thousands of dollars on behalf of the Soledad Brothers. She recruited celebrities like Dr. Benjamin Spock to the cause. Stender herself became something of a media celebrity, cultivating an intense, uncompromising radical persona. “I don’t use the expression ‘my clients’ anymore,” she said. “That expression is going out of my vocabulary and is certainly going out of my thinking. I feel that they are comrades.”

Jackson’s book, Soledad Brother, was Stender’s brainchild, selectively edited by her, a key element of her campaign to depict her client-in-chief as both hero and victim. It was a labor of love in the most literal sense, for just as she had with Huey Newton, she became George Jackson’s lover.

As her fame spread among the inmates of the California prison system, letters from other inmates, pleading for help, poured into Stender’s office. Her Soledad Brothers Defense Committee spawned a larger initiative: the Prison Law Collective. She believed that she had found her calling: fundamental reform of the criminal justice system. But in the process Stender lost — or abandoned — what little remained of her objectivity and caution.

To the radical activists of the New Left, the revolutionary apocalypse seemed close at hand. It was the time of the turn toward violence, exemplified by the terroristic Weather Underground. In the Bay Area, the Black Panthers and the police were virtually at war. It was easy for Stender and her comrades to romanticize men like Huey Newton and George Jackson—and fatally easy to forget that whatever injustices had been committed against them, such men in their hearts were violent criminals.

But gradually Stender’s eyes were opened to the reality behind the romance. Her growing celebrity annoyed and humiliated Jackson, who felt that it called his manhood into question. There were also disputes over money. Soledad Brother was generating considerable revenue, which Stender controlled. Jackson demanded that she cede control of the money to him. He wanted the funds to further his plans for a prison break and the creation of a revolutionary army. After an acrimonious argument, Stender gave in and relinquished control of the Soledad Brothers revenue.

Their stormy relationship finally ended when Jackson began pressuring Stender to smuggle weapons into San Quentin. She adamantly refused to do so—though as it transpired some of her comrades in the Prison Law Collective did not. But Stender was frightened now, and in February 1971 she stepped down from the Soledad Brothers case. It was her replacement, a lawyer named Stephen Bingham, who smuggled in the handgun that Jackson and his confederates used in their attempt to break out of San Quentin, where he was now being held. On August 21, 1971, Jackson made his bid for freedom. Three guards, two white inmates and Jackson himself were killed in the attempt.

Stender was devastated but not particularly surprised by the news of George Jackson’s bloody death, remarking that she knew it would end that way. Her escalating doubts about the propriety of the revolutionary cause caused a split between her and the true believers within the Prison Law Collective. In 1974 she closed the PLC and moved on from the criminal justice reform cause. She was through representing convicts, she said. Feminist issues came to attract her from the mid-Seventies onward and ultimately she came out as a lesbian. But her so-called treason was not forgotten, and there were persistent rumors that Jackson’s organization, the Black Guerilla Army, had her marked down for assassination.

Though she said little about it, Faye was bitter about her experience as a criminal justice and prison reform activist. She had come to see that both Newton and Jackson had used and discarded her. Also she came to terms with the revolving-door aspect of her activism: Sooner or later, most of the convicts whose release she procured ended up back behind bars. But despite everything there remained a place in her heart for the most mesmerizing revolutionary of them all, her client, comrade, and lover George Jackson.

When the doorbell of Fay Stender’s Oakland home rang on May 28, 1979, it was answered by her twenty-year-old son Neal. On the porch was a young woman wearing a blue hoodie. She immediately stepped aside and disappeared, revealing a man armed with a .38 caliber revolver. He pointed the weapon at Neal and demanded to know if this was Fay Stender’s house. Neal admitted that it was, and the intruder ordered him to take him up to his mother’s bedroom.

Faye was in bed with her lover, a young lawyer named Joan Morris (a pseudonym). The intruder, Edward Brooks, ordered Fay to sit at a desk and write down the statement he dictated, confessing that she had betrayed George Jackson and the revolutionary cause. She refused at first but eventually related. Brooks took the confession, pocketed it, and demanded money. Between Fay and Neal he collected ten dollars; she told him there was more downstairs in the kitchen. So Brooks ordered Neal to tie up Joan, and Fay to tie up her son. That done, he left them on the bed and followed Fay downstairs.

In the kitchen he demanded more money, which Fay handed over. Brooks’ total haul was around forty dollars. He then ordered her to precede him to the front door. In the hall he passed Fay, turned, assumed a two-handed shooter’s stance, and fired five times, hitting her in the stomach, chest and both arms. The fifth bullet grazed her skull.

In the bedroom, Neal heard the shots and Fay’s screams. Arms still bound behind his back, he rushed downstairs to find his mother prostrate on the hall floor in a pool of blood.

“I’m dying!” Fay sobbed. She was.

Bibliographical Note

Fay Stender’s story was first brought to my attention via “Requiem for a Radical” by David Horowitz and Peter Collier, which appeared as an article in New West magazine (1981) and later as a chapter in their book, Destructive Generation: Second Thoughts About the Sixties (1991). Horowitz, a leading light of the New Left who later recanted, lived in the Bay Area and worked with the Black Panthers as a “white ally.” He was well acquainted with Huey Newton.

Writing in the spring 1991 issue of On the Issues Magazine, Diana E.H. Russell, Professor of Sociology at Mills College (Oakland, California) analyzed Fay Stender’s life and death from a feminist perspective. Professor Russell’s account is of particular interest as she was personally acquainted with Stender and her lover, Joan Morris.

Fay Stender has also been the subject of a full-dress biography, Call Me Phaedra: The Life and Times of Movement Lawyer Fay Stender by Lise Pearlman (2018) Ms. Pearlman, a former a former trial lawyer and judge, is a leading authority on the Black Panthers, Huey Newton and the Bay Area revolutionary scene of the sixties and early seventies.

A wasted life. so much more could have been done with her intelligence and skills. Pearls before swine.

'Show me a hero and I'll write you a tragedy.' - Fitzgerald

In life we make choices without fully realizing the path we are taking.

Reading your description of 1968 made me realize that as much as 2024 worries us, it was arguably much worse back then. There was more anger then and (1/6 hysteria aside), more people willing to take up arms.

I was also struck by the similarities between the criminality of the activists then and Antifa/BLM now.

And the support of the useful idiots of the intellectual left.