With operations in the Balkans underway and the invasion of the USSR impending, the Blitz on Britain came to an end in May 1941. Germany’s 1940-41 strategic air offensive had neither destroyed the Royal Air Force, nor crippled Britain’s industrial base, nor collapsed national morale. To be sure, British infrastructure and industry suffered significant damage and some 41,000 civilians were killed. But thanks to inadequate equipment, poor intelligence and lack of strategic focus, the Luftwaffe had failed to deliver a knockout blow.

So Britain survived to fight on—but fight how? The Army having been ejected from continental Europe with no prospect of an early return, there seemed but one way of striking at Germany directly, and that was strategic bombing. Winston Churchill recognized this as early as June 1940. Before the war he had been somewhat skeptical of strategic bombing theory on both practical and moral grounds. But now, writing to Lord Beaverbrook, Minister of Aircraft Production, he struck a different note: “When I look round to see how we can win the war, I see that there is only one path…an absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland.”

These words, of course, were music to the ears of the RAF’s senior leaders, who despite all earlier disappointments remained convinced that strategic bombing was the key to victory. Around the time that Churchill was addressing the issue to Beaverbrook, Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, then commanding Bomber Command, wrote to the Deputy Chief of the Air Staff:

We [Bomber Command] have the one directly offensive weapon in the whole of our armory, the one means by which we can undermine the morale of a large part of the enemy people, shake their faith in the Nazi regime, and at the same time with the very same bombs, dislocate the major part of their heavy industry and a good part of their oil production.

Here was encapsulated the thinking that would lead to the devastation of urban Germany and the death of some 400,000 German civilians.

But the results obtained during RAF Bomber Command’s initial 1939-41 operations had been far from satisfactory, revealing that the gap between theory and practice remained wide. Heavy losses had ruled out precision daylight bombing, and night bombing, though it reduced those losses, proved ineffective. With the aircraft and technology available it was extraordinarily difficult to locate and bomb targets at night, even under ideal weather conditions, and as late as May 1941 Bomber Command estimated that 35-50% of the bombs dropped by its aircraft were landing in open country.

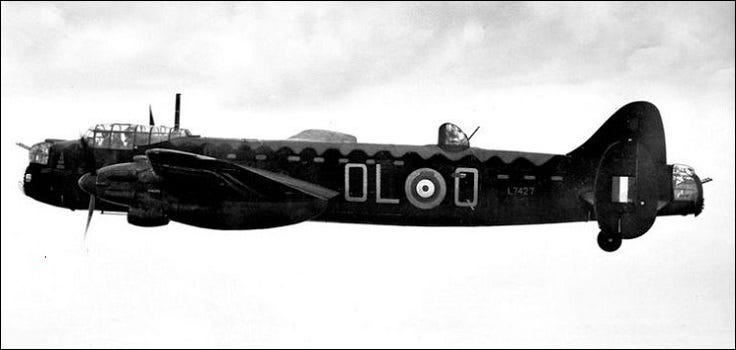

There were occasional successes, such as Operation ABIGAIL-RACHEL against Mannheim on the night of 16/17 November 1940. Its methodology foreshadowed the much more destructive attacks of 1943-45. Some 200 aircraft took part, the whole force being led by a special detachment of Wellingtons carrying a maximum load of 4lb incendiary bombs. The fires they started would, it was hoped, guide the main force to the target. Weather conditions and visibility were favorable, and two-thirds of the attacking aircraft found and bombed the city. Seven aircraft were lost.

Compared with earlier operations ABIGAIL-RACHEL was judged a success, subsequent photographic reconnaissance showing that considerable damage had been done to various areas of Mannheim. On the other hand, the bombs dropped had been widely dispersed and this reduced the effectiveness of the attack. It was clear that more bombs, better accuracy, and a clearly articulated policy were needed.

Then a bomb landed on the RAF, in the form of the Butt Report. In August 1941 Churchill’s chief scientific adviser, Professor Frederick Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell), had commissioned D.M.B. Butt of the War Cabinet Secretariat to conduct a statistical review of Bomber Command’s attacks on German targets. Butt examined some 650 photographs taken during 100 attacks on 28 separate targets. The results were devastating. Butt estimated that only a third of the aircraft claiming to have reached and bombed the primary target had actually done so. Since around 65% of aircraft dispatched had claimed to have found the target, this meant that on average only a fifth of the bombs dropped were hitting their intended target. Moreover, since the target point was defined as a circle with a radius of five miles, its size was 75 square miles—which in in most cases encompassed a good deal of open country.

Sir Charles Portal, by then Chief of the Air Staff, and his successor at Bomber Command, Air Marshal Sir Richard Peirse, both thought that the Butt Report exaggerated an admittedly unsatisfactory state of affairs, but they could only agree with the Prime Minister, who described it as “a very serious paper and seems to demand your most urgent attention.” Churchill, indeed, had grown somewhat skeptical of the RAF’s extravagant claims on behalf of strategic bombing. In response to Portal’s assertion that with a force of 4,000 heavy bombers, Bomber Command could totally destroy the forty or so largest German urban centers, he wrote:

It is very disputable whether bombing by itself will be a decisive factor in the present war. On the contrary, all that we have learnt since the war began shows that its effects, both physical and moral, are greatly exaggerated…. The most we can say is that it will be a heavy and I trust a seriously increasing annoyance.

This can hardly have made pleasant reading for Portal, Peirse and their RAF colleagues.

Over-pessimistic though it may have been, the Butt Report served the purpose of focusing the Air Staff’s attention on the problems of navigation, target location and bombing accuracy by night. Hitherto, reliance had been placed on dead reckoning and the sextant—both of which had proved utterly inadequate. Now the search began for fresh technological and tactical solutions, though it would be some time before these were forthcoming.

Overall, 1941 was a year of frustration for Bomber Command. Not only did its operations yield unimpressive results, attracting sharp criticism from the Prime Minister, but its expansion to the size deemed necessary for improved performance proved exasperatingly difficult. The great need was for true heavy bombers to supplement and eventually replace the twin-engine Wellingtons, Whitneys and Hampdens. Such aircraft had been in development since 1936 but their service introduction was much delayed by various teething troubles, especially as regards engines.

Great hopes had been vested in the Avro Manchester, whose innovative design featured two propellers, each driven by two engines with a common crankshaft. It was a clever idea but the engine installation proved unreliable and though the Manchester entered service in late 1940 it never equipped more than eight squadrons and was withdrawn from service within a year. The Short Sterling was more successful, though it too had some significant design issues. The Sterling had a short wingspan for its size, which restricted its operational ceiling. And though it could carry a heavy bomb load, the design of the bomb bay was such that no bombs larger than 2,000lb could be accommodated. The Sterling entered squadron service in early 1941 and soldiered on until late 1943, when more capable heavy bombers became available in quantity.

One of these was the Handley Page Halifax, which entered service in late 1941. Early versions had performance problems due to insufficient engine power, but once this was corrected the Halifax proved to be a most effective heavy bomber. Finally there was the Avro Lancaster, one of the war’s most outstanding combat aircraft. Its design was based on that of the failed Manchester, albeit with a conventional four-engine/four-prop power installation. The Lancaster entered service shortly after the Halifax—heralding the transformation of Bomber Command into the formidable force it became in the second half of the war.

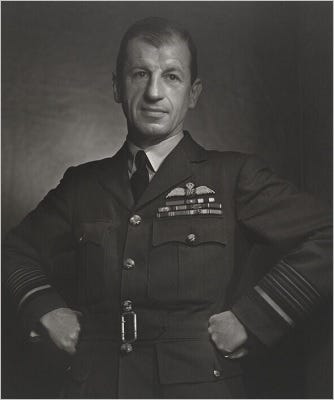

One other ingredient was wanting in the effort to guide Bomber Command through its time of troubles: effective leadership. Sir Richard Peirse was a capable officer who since his appointment in October 1940 had grappled as best he could with a challenging set of circumstances. But by the end of 1941 he was worn out. The disastrous night of 7/8 November 1941, when Bomber Command lost almost 26% of the 143 aircraft that managed to reach their targets, led to a virtual suspension of operations—and there were many, Portal among them, who felt that Peirse was losing his grip. Accordingly, in February 1942 he was relieved of command and transferred to the Far East as commander of Allied air forces in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. His replacement at Bomber Command headquarters was a man whose name was to become synonymous with the devastation of urban Germany: Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris.