A Necessary Evil

Seventy-eight years ago this month, atomic bombs destroyed two Japanese cities

Author’s Note

Last year on this date, I published on Substack this article about one of the most consequential decisions any American president ever made. Reading it over a year later, there’s nothing I’d change.

In August 1945 my father, George W. Gregg, Sr., had been serving on sea duty in the US Coast Guard since late 1942. Upon Germany’s surrender his ship, a troop transport operating in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, was decommissioned. Its entire crew was sent to San Diego, there to retrain as landing craft crewmen for the projected invasion of Japan. Needless to say, Dad had no problem with President Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb. For him and his shipmates, it was a blessed reprieve.

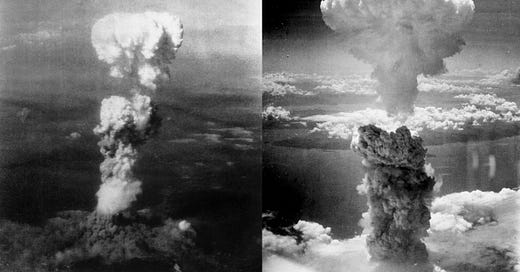

The decision to employ atomic bombs against Japan in August 1945 remains one of the most controversial episodes of the Second World War. Over the years critics have gone so far as to allege that it was an act of barbarism, indeed a war crime, since Japan was already on the brink of military defeat, with its armed forces shattered, its cities in ruins, and its government seeking a path to surrender. These criticisms and condemnations cannot be summarily dismissed. Even in the context of a catastrophic global war, the atomic bombing of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki seemed truly horrific—a frightening harbinger of even greater destruction to come. And though American public opinion approved of the attacks, accepting the pragmatic argument that the atomic bomb had brought the Pacific War to an end, there were many who asked: Was this really necessary? The question persists to this day.

It's true enough that by the summer of 1945, Japan had no hope of winning the war, or even of staving off total defeat. It’s also true that a faction within the Japanese government understood the grim realities of their country’s plight and accepted the necessity of surrender. But there was another faction that refused to accept the reality of defeat and believed that Japan could still salvage something from the debacle. The high command of the Japanese Army stood firm against surrender, and it had the means to make its opposition effective.

Japan’s senior soldiers wielded real political power, and the stability of any Japanese government depended on Army support. Constitutionally, the Minister of War answered not to the prime minister but to the Emperor. Moreover, a 1936 law stipulated that the position had to be filled by an Army general officer on active duty, nominated by the high command. This gave the Army effective veto power over government policy: By ordering the Minister of War’s resignation from office, his brother officers could cause the government to fall.

And these legalities were backed up by the threat of violence. The Army was deeply implicated in radical right-wing politics and many officers belonged to nationalist secret societies with a record of political terrorism. In August 1945, those members of the Japanese government who favored ending the war had good reason to fear that openly advocating surrender would lead to their assassination in a military coup.

For the Army’s leaders were bent on a fight to the finish. Despite all the military disasters that Japan had endured, the main body of the Imperial Japanese Army had not yet been engaged and defeated in battle. Stationed in the Japanese Home Islands were some three million troops, equivalent to about 65 divisions. Taking into consideration equipment and ammunition shortages, about 40 divisions could be fielded and this, the Army leadership judged, would be sufficient for the final battle it contemplated. The generals believed that such a battle on Japanese home soil would be so bloody as to induce the enemy to settle for something less than the unconditional surrender demanded in the Allies’ Potsdam Declaration.

That they could count on an opportunity to fight that battle was never in doubt, for it was obvious that the enemy intended to finish the war by invading the Home Islands.

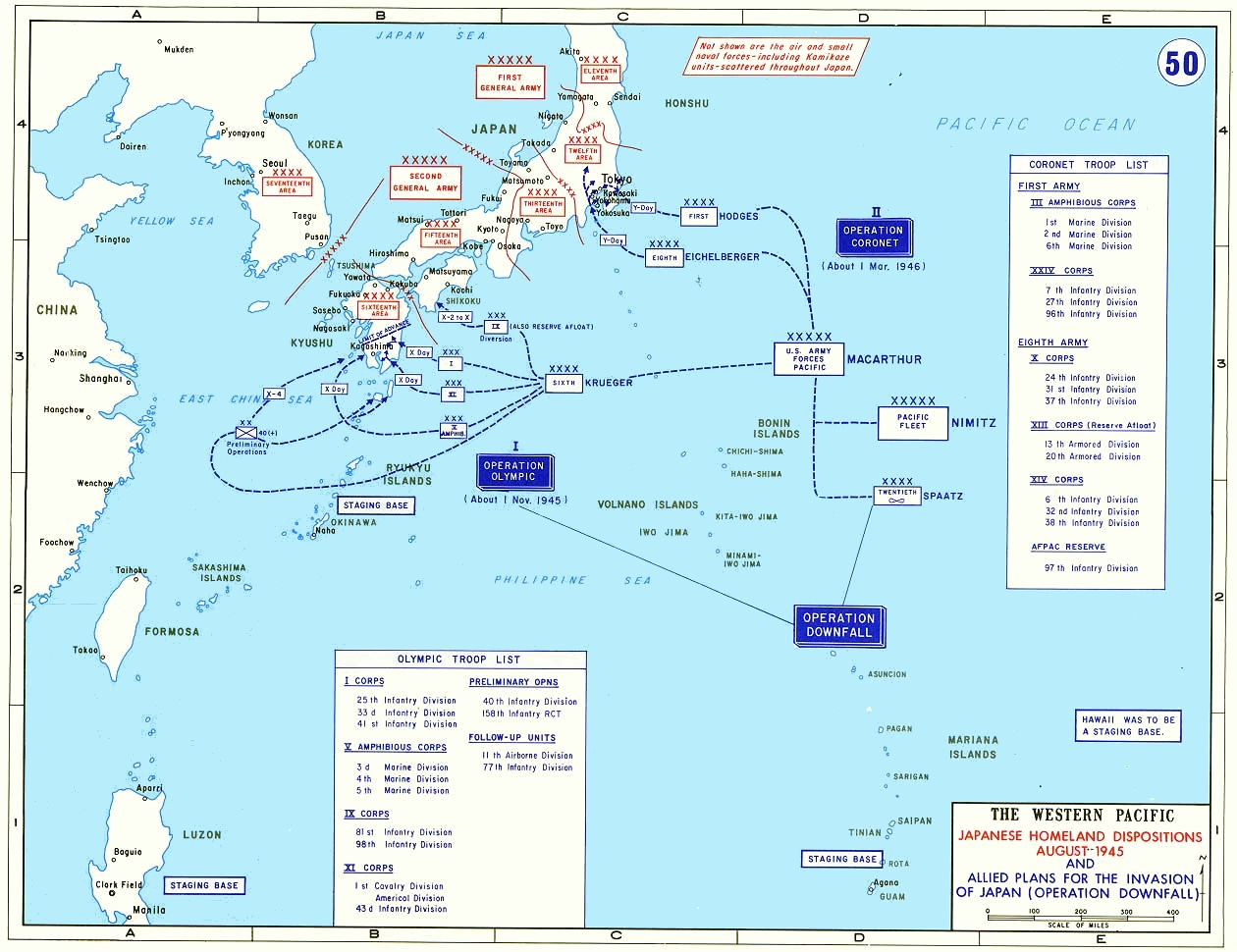

On the Allied side, detailed planning for just such an invasion commenced in early 1945 under the code name DOWNFALL. As finalized, the operation would take place in two phases. Phase one, codenamed OLYMPIC and scheduled for November 1945, had the objective of invading and occupying the southern third of Kyūshū, the most southerly of the Home Islands—this to provide a base from which to launch the second and main phase, codenamed CORONET, the invasion of Honshu, the largest of the Home Islands and Japan’s industrial heartland. The initial landings would take place south of the capital, Tokyo, with a view to encircling the city and advancing north over the Kantō Plain toward Nagano, where the final, decisive battle would be fought.

From the beginning, there was considerable disquiet concerning the Allied, primarily American, casualties likely to be suffered during this final campaign. Early, relatively optimistic, estimates were soon revised upward in light of experience gained during the Battle of Okinawa, plus new intelligence on Japanese capabilities and intentions.

The battle for Okinawa raged from 1 April to 22 June 1945, and by the time it had run its course, US casualties totaled 50,000: 12,500 killed in action or missing in action, and 36,122 wounded in action. There were also some 30,000 fatal and nonfatal casualties due to battle fatigue, illness, and accidents not connected to combat—this out of some 250,000 combat troops engaged, or 300,000 if the crews of naval vessels are included—as well they should be. More than 100,000 Japanese troops were killed, along with thousands of Okinawan civilians, perhaps as many as 150,000.

Following Okinawa, revised estimates of the toll that DOWNFALL was likely to take on the invaders ranged from a million and a half to four million total casualties, with 400,000-800,000 dead. Japanese casualties, military and civilian, were forecast to total between five and ten million.

Even assuming that the above numbers were far too pessimistic and should have been revised downward, even halved, the outlook remained grim.

Such a bloodbath was precisely the aim of the Japanese Army high command. While the Battle of Okinawa was still going on, Imperial General Headquarters issued its “Outline of Preparations for Ketsugō Operation” (Ketsugō means decisive battle). Ketsugō envisioned an all-out defense in depth supported by local and operational counterattacks, forcing the invader to fight a protracted battle of attrition. The Japanese foresaw that the Allies would invade Kyūshū first, and the pattern of their deployments suggested that they intended to fight their final battle on that ground.

On Kyūshū, the front line of defense was located inland from the probable invasion beaches, far enough back to escape the full effects of the prelanding naval bombardment, but close enough to force the enemy to engage them before consolidating a beachhead. The Japanese troops were sited in deeply dug defensive positions: trenches, dugouts, bunkers, concrete artillery emplacements and underground galleries connected by tunnels through which reinforcements, guns and supplies could be moved without being observed. As Iwo Jima and Okinawa had demonstrated, such fortifications could only be reduced slowly, and at high cost.

Worse still from the Allied point of view, Ketsugō relied heavily on “special attack,” i.e. suicide, tactics. The Kamikaze (Divine Wind) air strikes on the US fleet off Okinawa had taken a grievous toll: 36 ships ranging from destroyers to small landing craft sunk, with another 24 so badly damaged that they never returned to service. In all, 147 ships were sunk or to some extent damaged. US Navy casualties amounted to 4,907 killed in action and 4,824 wounded in action. As one sailor who was there later recalled, it was “a fight to the finish.”

By July 1945 the Japanese had more than 10,000 planes in the Home Islands, most of which were designated for special attack missions. They were supplemented by the Imperial Japanese Navy’s special attack craft: suicide speedboats packed with explosives, that would ram enemy vessels. Some 2,500 of these Shinyo (Sea Quake) boats were available by July. The Navy also had about 500 midget submarines ready for action. Their crews were briefed to attack amphibious transports, cargo ships, and landing craft in preference to warships. The Navy’s few remaining warships, mostly destroyers, were to be expended in mass attacks on the invasion fleet.

Finally, there was the Volunteer Fighting Corps, a civilian militia. All men between the ages of 15 and 45, and all women aged 17 to 40, were liable for service. The militia was to be called out when the threat of invasion was imminent, armed with a miscellany of outdated firearms, hand grenades, Molotov cocktails, swords, pikes, bows and arrows, even clubs. The militia was tasked to back up regular Army units, and to conduct guerilla operations behind enemy lines. By August 1945, some two million civilians, primarily on Kyūshū, had been mobilized for militia service.

DOWNFALL involved a major redeployment of US forces from then European Theater of Operations to the Pacific: US First Army with fifteen divisions and the entire Eighth Air Force. Britain’s initial contribution was the British Pacific Fleet with 200 ships, including six fleet aircraft carriers, nine escort aircraft carriers, four battleships, eleven cruisers, 35 destroyers and numerous small warships and support ships. It says something for the scale of DOWNFALL that this armada, the largest assembled by the Royal Navy during the war, was but a small component of the Allied fleet. As for ground forces, initial planning envisioned the use of US troops only, but later the Commonwealth Corps, composed of British, Australian, Canadian and New Zealand formations, was added to the order of battle. Units of the British, Australian and Canadian air forces were also slated to take part.

OLYMPIC was to be executed by US Sixth Army, with twelve Army and three Marine divisions under command. CORONET was to be executed by US First and Eighth Armies, with 25 Army and Marine divisions under command, rising to 45 divisions as the campaign developed.

But while the Allied commands were marshaling their forces and perfecting their plans, a secret project unknown to all but a handful of politicians, senior officers and scientists was coming to fruition. On 16 July 1945, the first test of a nuclear weapon took place at Alamogordo Army Air Field, New Mexico. Code named TRINITY, the test produced an atomic explosion with a yield equivalent to 20 kilotons of TNT. Thus did the top-secret Manhattan Project provide President Harry S. Truman, who had assumed office on 12 April following the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, with an alternative to DOWNFALL. As vice president, he had been told nothing about the atomic bomb. When briefed on it, however, Truman confirmed his predecessor’s authorization to employ atomic weapons against Japan. Already in February 1945 it had been decided to deploy the US Army Air Force’s 509th Composite Group to the Pacific. Since its activation in December 1944, the 509th had been training for the atomic mission, and now it would be committed to action.

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson drew up the list of targets, which included the cities of Hiroshima (southern Honshu) and Nagasaki (western Kyūshū). Hiroshima was struck on 6 August 1945 and Nagasaki was struck three days later. In total, the atomic bombings killed some 150,000-200,000 people, almost all of them Japanese civilians. The surrender of Japan followed in short order.

But neither atomic bombing qualified as the war’s most destructive air attack. That record is held by Operation MEETINGHOUSE (9-10 March 1945), a low-level night attack on Tokyo by B-29s of the US XX Bomber Command. Most of the bombs dropped were incendiary devices of one type or another and they ignited a holocaust that leveled sixteen square miles of the city and killed an estimated 100,000 people.

Even so, the atomic attacks administered a shock to the Japanese political system. As the realization dawned that a single bomb had destroyed each city, Army leaders began to rethink their insistence on a final, glorious battle. Suddenly the Potsdam Declaration’s promise of “prompt and utter destruction” unless Japan surrendered seemed terribly plausible. The Japanese had no way of knowing that America’s supply of atomic bombs was limited: A third one might become available in mid-August, three more in September, and perhaps another three in October.

The bombings also stirred the Emperor to action. For some time, Hirohito had quietly favored surrender. But though an absolute monarch in theory, by custom he was a figurehead above politics. On 10 August, however, at a specially summoned imperial conference, he informed the government of his “sacred decision”: The time had come to bring the war to an end. He communicated his decision to the Japanese people in a radio broadcast on 14 August. Hostilities ceased the following day; the formal instrument of surrender was signed in Tokyo Bay aboard the battleship USS Missouri on 2 September 1945.

There can be no doubt that the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki hastened the end of the Pacific War. What would have happened if no atomic bombs were available, or if President Truman had decided against using them, is an interesting albeit speculative question. Uneasiness over the casualties likely to be sustained in DOWNFALL had indeed prompted suggestions that some different strategy might be preferable. Admiral Ernest J. King, the Chief of Naval Operations and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet, thought that blockade and conventional air bombardment could break Japanese resistance at much lower cost. But that would have prolonged the war by months if not a year or more, and would certainly have led to mass starvation and disease within Japan. There were also proposals to employ chemical weapons against the Japanese defenders. This was vetoed by President Truman.

The Soviet Union declared war on Japan and launched an invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria on 9 August, the same day that Nagasaki was destroyed. The Japanese defenders, embodied in the Kwantung Army, were quickly defeated. But the Red Army had no plans in place to follow up with its own invasion of the Home Islands. It seems doubtful, therefore, that the invasion of Manchuria, absent the US atomic attacks, would have caused the Japanese government to throw up the sponge. It is telling that even after the bombings, the Soviet invasion of Manchuria and the Emperor’s broadcast, a clique of Army officers launched a coup to prevent Japan’s surrender. But they got no support from the senior generals, most of whom were prepared to obey Hirohito’s orders.

If the atomic bomb had not been a factor in the situation, the first phase of DOWNFALL, Operation OLYMPIC, would probably have gone ahead—resulting in a desperate battle with very high casualties, perhaps triple those sustained on Okinawa. If so, the toll on the American side would have been about 40,000 killed in action or missing in action, and 140,000 wounded in action. On the Japanese side, around 300,000 military personnel and 500,000 civilians would have been killed. Very likely defeat on Kyūshū would have impelled the Japanese government and high command to accept surrender, rendering CORONET, the invasion of Honshu, unnecessary. But even so, Allied victory would have come at a high price.

In short, President Truman made the right call. Horrific as the atomic attacks were, they saved many lives, American and Japanese.

However, these practical considerations do not really address, much less refute, the moral case against the atomic bombings, with which I will deal in a subsequent article.

It’s surprising to think that one atomic bomb did not provoke a surrender; it required two.

This is an excellent short summary. I studied this era in detail in the 1970s and my views have not changed. The casualty levels on Okinawa are telling as to what to have reasonably expected in a full scale invasion of Japan. I always suggest people watch The Pacific to understand the brutality of the fight against Japan. Reading about deaths and casualties can never explain the pure mayhem and terror of the war. I personally knew 2 people who were scheduled to fight in an invasion of Japan. They lived long, productive lives and were absolutely convinced Truman saved their lives and that of their children and grandchildren who they believed never would have been born. It’s hypocritically easy to be a Monday morning quarterback almost 80 years after a monumental event where humans had to make the kind of decision Truman had to make. He made the correct decision.