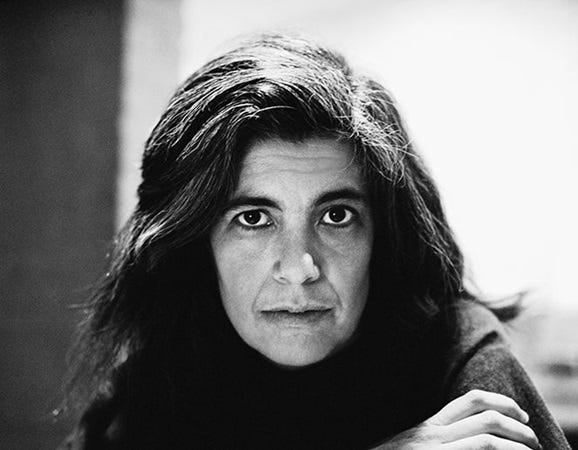

Here’s some recommended reading on a hot topic. Susan Sontag’s essay “Fascinating Fascism” (The New York Review of Books, February 6, 1975) is, first, a biting takedown of Leni Riefenstahl, who was still around at that time, and was not to die until 2003. (Sontag herself died in 2004.) Second, it’s a profound meditation on the nature of fascism, a world away from the puerile rants that pollute social media in these fallen times.

Riefenstahl, you will recall, was the German film director and producer who won fame —or notoriety—for her two film documentaries of the 1930s: Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will, 1935) and Olympia (1938). Triumph des Willens chronicled the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nurenberg; Olympia documented the 1936 Olympic Games, which were held in Berlin. Both films were hailed in their day as masterpieces; Triumph des Willens won the German Film Prize, a gold medal at the 1935 Venice Biennale, and the Grand Prix at the 1937 Paris World Exhibition.

Today, however, the two films have an equivocal status in the history of cinema. Though regarded as cinematic landmarks on grounds of technical brilliance, their exultation of Hitler and National Socialism strikes a jarringly discordant note. Watching Triumph des Willens especially, the thoughtful viewer cannot but reflect on the world-historical horrors that were to come before the Twelve-Year Reich went down in flames. And this, the study in contrasts between Riefenstahl’s triumphant vision of a national awakening and the apocalyptic realities of industrial genocide, dogged the filmmaker’s footsteps for the rest of her life.

After the war, Riefenstahl was arrested as a Nazi “fellow traveler,” though she was never charged with war crimes. To the day of her death, she denied knowing anything about the Holocaust or other crimes of the regime, and she made herself out to be an apolitical artist who had to fight Nazi officialdom for the sake of her cinematic vision. In particular, she claimed that Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment who controlled the German film industry, was her bitter enemy. The reality was otherwise. Riefenstahl was a close personal friend of both Hitler and Goebbels, and she worked closely with the latter and his ministry to produce what must be acknowledged as the two most effective propaganda films ever made.

In her essay, Sontag systematically deconstructs Riefenstahl’s apologia, and it’s startling to learn that despite the celebrated filmmaker’s Nazi background, she had by the 1970s regained a certain degree of respectability. “It is not that Riefenstahl’s Nazi past has suddenly become acceptable,” Sontag writes:

It is simply that, with the turn of the cultural wheel, it no longer matters. Instead of dispensing a freeze-dried version of history from above, a liberal society settles such questions by waiting for cycles of tastes to distill out the controversy.

That American and European cultural elites were willing to pass over Riefenstahl’s Nazi past betrays a persistent lack of moral seriousness. In 1975, she was actually the guest of honor at a prestigious film festival held in Colorado, and her defenders included some of the most influential figures in the avant-garde film establishment. “Part of the impetus behind Riefenstahl’s recent promotion to the status of a cultural monument surely owes to the fact that she is a woman,” Sontag notes sourly—and no doubt accurately. “Feminists would feel a pang at having to sacrifice the one woman who made films that everyone agrees to be first-rate.” That’s an observation that strikes home today like an arrow at Agincourt. In the first quarter of the twenty-first century, have not numerous “anti-Zionist,” i.e. antisemitic, poets, writers, and whatnot been feted by the arts establishment?

All this goes to show, perhaps, that it takes one to know one, for if Leni Riefenstahl was a monstrous genius, Susan Sontag was something of a monster herself. She was notorious for her rudeness to the little people—cab drivers, waiters, store clerks—and for a certain indifference to matters of personal hygiene. As Oliver Basciano put it in a recent article for ArtReview, Sontag was “a quintessential New Yorker…the embodiment of all that is narcissistic, venal and self-aggrandising [sic] in that most inwardly fragile of cities.” And it’s plausible to think that Sontag, a Jew whose attitude toward Israel was equivocal at best, might today be siding with the anti-Israel Left. Be that as it may, however, she had Leni Riefenstahl’s number.

Having spelled out the Nazi propagandist’s postwar record of distortions and outright lies, Sontag goes on to discuss the continuity of vision that characterized Riefenstahl’s work as a filmmaker. And that vision, she argues, was essentially fascistic. But, important to note, Sontag’s indictment is not based on fascism as an ideology or a political movement, but on fascism as a cultural phenomenon.

Here we have a mode of analysis that has fallen by the wayside in these philistine times. Amid all the warnings of creeping fascism that arise from the progressive fever swamps, there’s little or no acknowledgement that fascism, properly understood, includes its role as a manifestation of culture: that there is, in fact, such a thing as a “fascist aesthetic.” And the arc of Riefenstahl’s career, from her early film work to The Last of the Nuba, the book of photographs that serves as Sontag’s entry argument, is, so to speak, a documentary record of that aesthetic:

Fascist aesthetics include but go far beyond the rather special celebration of the primitive to be found in The Last of the Nuba. More generally, they flow from (and justify) a preoccupation with situations of control, submissive behavior, extravagant effort, and endurance of pain; they endorse two seemingly opposite states, egomania and servitude. The relations of domination and enslavement take the form of a characteristic pageantry: the massing of groups of people; the multiplication or replication of things; and the grouping of people/things around an all-powerful, hypnotic leader-figure or force. The fascist dramaturgy centers on the orgiastic transactions between mighty forces and their puppets, uniformly garbed, and shown in ever swelling numbers. Its choreography alternates between ceaseless motion and a congealed, static, “virile” posing. Fascist art glorifies surrender, it exalts mindlessness, it glamorizes death.

I quote this passage at length because in it, Sontag limns a prose picture of the ceremonies depicted in Triumph des Willens. It was in this guise that Italian Fascism, National Socialism, and their imitators chose to present themselves to the world. Indeed, the term totalitarian aesthetic is suggested, the displays of mass enthusiasm and devotion staged under Stalinist Bolshevism, Maoist Communism, and North Korean Juche having many affinities with those of the twentieth-century fascist regimes.

There can be no doubt that were she alive today, Susan Sontag would revile Donald J. Trump and all his works. She was, after all, a woman of the Left. It’s to be doubted, however, that she would find in MAGA populism the fascist aesthetic so vividly described in “Fascinating Fascism.” Whatever criticism might be leveled at it, the political phenomenon exemplified by Trump is not fascistic in Sontag’s terms. And in that sense, her indictment of fascism is equally an indictment of the hollow Hitler shouters on the intellectually degraded postmodern Left.

Susan Sontag’s essay, “Fascinating Fascism,” may be found in the second volume of her collected essays, published by the Library of America. As a charter subscriber to LoA, I can attest to its inestimable value as the definitive compilation of American literature in all its variety and richness, and to its role as the cornerstone of my personal library.

Being not as smart as those who feel entitled to tell me what to think and how to live, I try to rely on “common sense”. Born with a brain to think for myself. I see more evidence in Nature of a Creator, and Natural Laws (upon which science relies) than not. Being born with free will from my Creator, not government, allows me to choose what to think and how to live (assuming I recognize the same is true of others). Therefore, it seems simple to differentiate between those who recognize individual rights and responsibility vs collectivists (special privileges for any group), which ALWAYS violate someone else’s individual rights (the test: name one that doesn’t). All the “isms” boil down to this, at least for me: “Your rights end where mine begin and vice versa, don’t tread on me.” Everything else is only a question of “to what degree” of a totalitarian are they? I trust God, my Creator, all others “pay cash” (and with mankind ALWAYS follow the money).

On a side note, I learned what USAID is this week. Don’t watch this if you are easily offended: https://x.com/JOKAQARMY1/status/1886613298608521501

How are those cheap eggs, hm? Nazi.